Dancing With Death is the sixth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the second chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

Apart from a select few Beta readers, this particular story has not been shared before!

If you enjoy this Tale and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

The Shafts

Flin’s room was simple, but it was her room. Clean, solidly furnished, with a window opening out over the city below—a window with real glass—the view suggesting the sea, somewhere in the mists and beyond the rooftops spread below like giant steps, speckled with gulls and other birds. Of all the places she had stayed, she had rarely experienced a room as comfortable as this one. The pillow was full of feathers, the chair upholstered, even the bed linen would be exchanged and washed every week. A whole room, just for her.

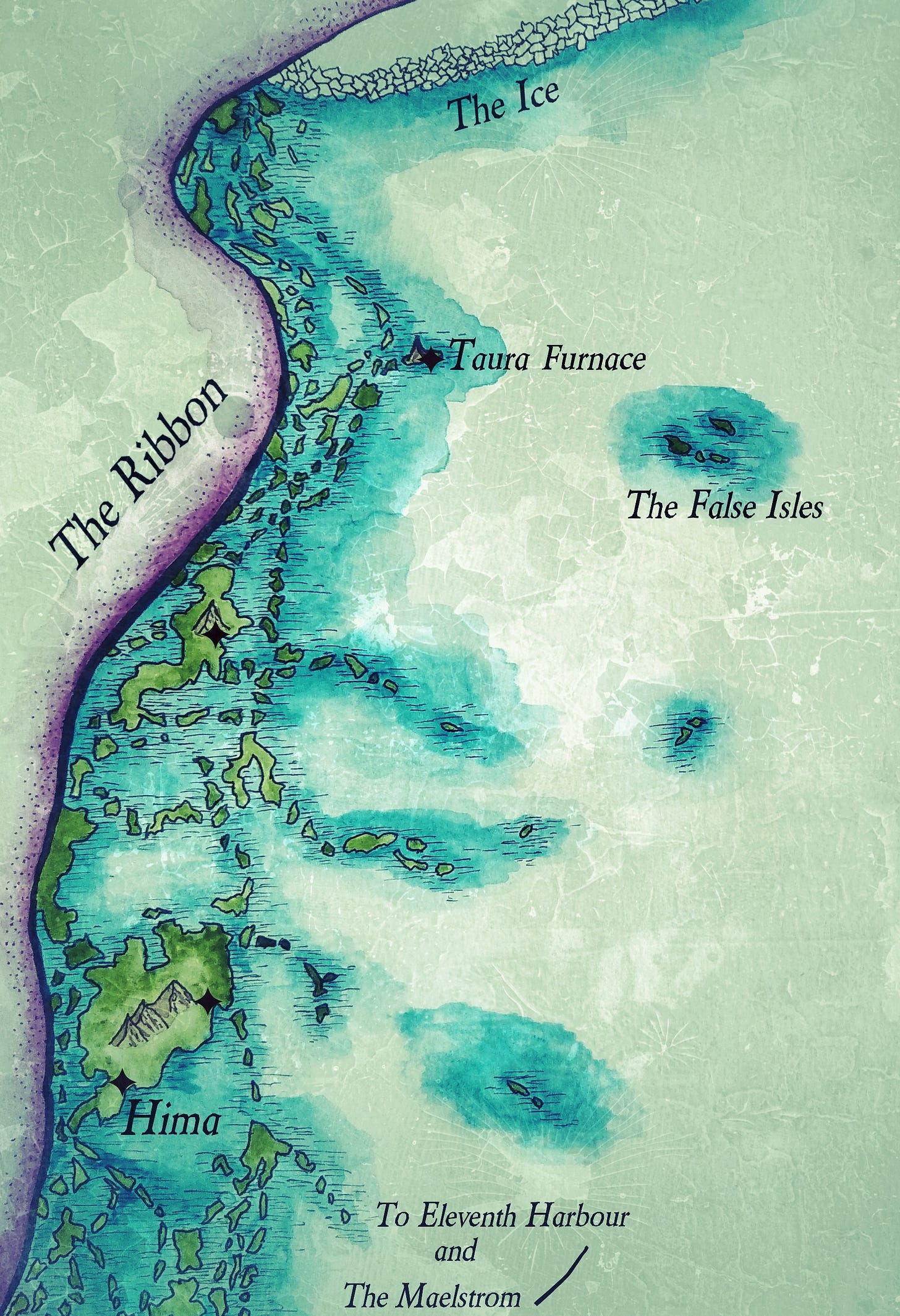

The terms of the contract they negotiated gave her one night off every week, and a full four day break once a month, but she also had the first three nights to do as she pleased—Ana had insisted she would not start until she was rested and ready. She had been adamant that there was no point in risking a voice weary from the long sea voyage, and the different air on Taura Furnace made it wise to adjust. Again, it was unexpected and made Flin feel welcomed, normally she would have to perform immediately.

Ana suggested she stay at The End for the first night, to see what the clientele were like, to see who else performed, and to tailor her own billing to fit. Two nights a week would be spent leading dances in the bigger room, a backing band provided. She would rehearse with them first, prepare and learn new material where needed, check she knew the steps and learn new dances where necessary.

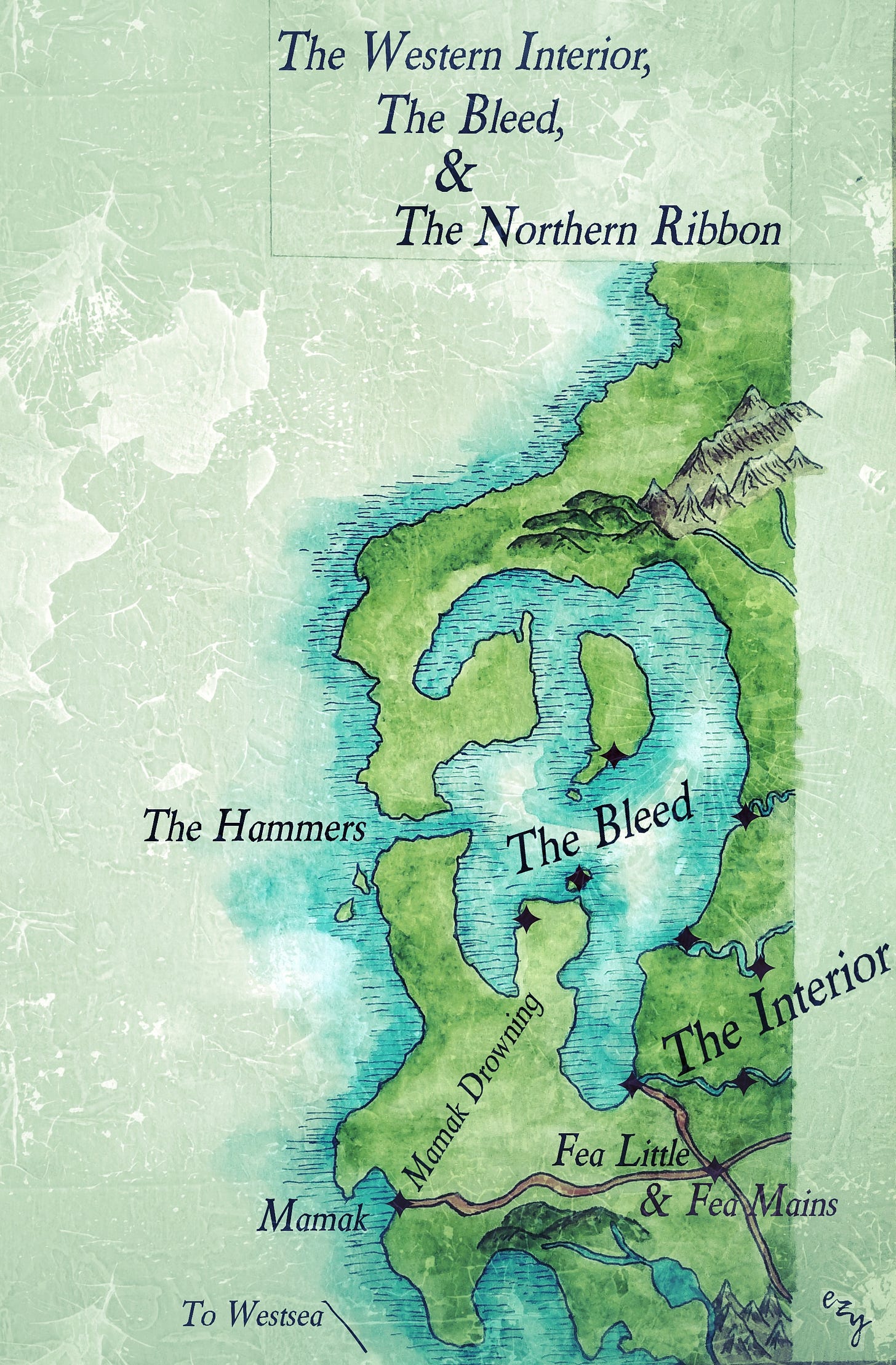

The other nights were left to her to choose what to perform. If there were a smaller number of clients then she would probably sing a few songs, telling more tales as her grasp of the language increased, or even tell stories in languages from The Interior or The Isthmus. Taura Furnace was built on trade and, where there was trade, most people spoke more than one tongue. The more people, the less likely they would be quiet for her work and, in those circumstances, it was better to play and sing popular tunes, provide background music. Flin knew what she was doing—she had been performing for over a dozen years, if she counted her apprenticeship.

The food was excellent, the staff friendly and welcoming. Ana oversaw everything, but was a calming, familiar presence, rather than a tyrant. Albin ran the kitchens, and took great pride in doing so, creating fantastic dishes with the cook, from a range of different cultures and cuisines, despite never having left the island. Every so often Flin would see him talking with sailors or travellers, asking about the dishes they knew, encouraging them to help him add to his repertoire in exchange for a free meal. The smell of spices and herbs was ever-present and alternating, a constant swirl of scent.

That first evening, Flin truly relaxed. She had dressed in her smartest clothing and spent the time observing the crowd and studying the other performers from where she sat, tucked in a corner. She drank wine, good wine from The Isthmus and other places she had never even heard of, but she made her drinks last, alternating with water.

When she headed to bed, many hours later, she felt comfortable, knowing the sailor had been right. She felt at home, glad she had signed for the spring season, get some money into her belt pouch, before she began her journey and the search to the south. She slept well and, for a change, dreamt little. That in itself was a powerful blessing.

‘What will you do today?’ Albin asked, from where he sat opposite Flin, polishing reflective plates from the inn’s lanterns.

‘I think I will go exploring. See something of the street life. I find it is useful to get a taste of a place.’

‘You should head to the upper city slopes, go visit the Shafts.’

‘The Shafts?’ Flin paused, spoon partway to her mouth.

‘You’ve not heard of them?’ he asked. He placed the rag he was using on the table, before continuing, ‘Have you noticed the streets?’

‘The streets?’ Flin was aware she was simply repeating words and added, ‘No, what do you mean? The cobbles? The steam?’

‘That is part of it, I suppose, but no. I meant how clean they are. We have few outbreaks of disease here, the Taura Blacksmiths, or The Forge, that’s what we call our council leaders, they say it is due to how to we get rid of our rubbish.’

Flin suppressed a shudder, remember the last exceptionally clean city she had stayed in. Things had not fared well for Youlbridge, despite its cleanliness.

‘The Shafts are a part of this,’ Albin continued, picking up the rag and polishing furiously, ‘The entire island is riddled with holes, with caverns, tunnels, pits and hollows. Mostly made by the mountain herself, by Taurie. Some of these holes descend all the way down, a long way down to liquid rock and fire. We throw our rubbish down there,’ he paused, ‘and we also use some of them for the dead. We do not bury our people here.’

Flin ran her finger over the scar on her forearm, remembering the tunnels beneath Youlbridge. She forced the thought away, breathing slowly and deeply, recalling the calming techniques she had been taught in the months after she had fled the city.

‘You throw your dead into holes?’ she asked.

‘It’s a little more complicated and respectful than that, but essentially, yes, I suppose that’s exactly what we do. If you follow the street uphill and turn left at the top, then take the steps leading past the Blacksmith’s Forge buildings, you will reach one of the most famous and beautiful Shafts. Go have a look, it is worth the climb, trust me and, if the fog lifts at all, the view is spectacular.’

Some time later, Flin found herself taking stair after stair, sweating, breathless, hot, uncomfortable and cursing Albin in several languages. The climb was long and painful and her legs felt afire. It had been more than a year since she had last been in mountain country, and the change from walking on the flat hurt. She was out of practice.

The stair seemed to go on forever, lined with houses built into—or from—the mountain, all made from the same black volcanic rock. The effect was strangely beautiful, a city that in many ways was uniform, the dark rocks giving the whole a sense it had been created all at once, perhaps overnight—another similarity to Youlbridge.

For their entire length, the centre of the steps held an ornately carved hand rail, scaled and long, the head of some sort of snake or sea serpent resting at the base of the climb. The germ of a new song nagged at her, and Flin was so engrossed in the idea she was surprised when she reached the end of the stair and the tip of the serpent’s tail at the top, aching muscles forgotten.

A squat building stood opposite, across a wide square, men and women stretched in curved lines in front, all marshalled and shepherded by a flock of priests in deep red robes, the queues a human echo of the snake she had followed. She wondered if that was deliberate.

Taura Furnace, Flin knew, had its own religious customs, developed by their proximity to the great mountain towering above, as well as their location as a nexus of trade, a crossroads of cultures and the last great city before the ice.

Flin stood and watched as people carried offerings inside, each bowing deeply to every red-robed figure they passed. All in the lines carried offerings, but a group of people who were entering a side door had none and Flin decided to follow them.

She climbed more stairs to a wide viewing platform, which stretched the width of the rear of the temple building, which was unroofed and open, sitting directly beneath the empty mountainside above. The platform was sparsely dotted with people standing together in small groups, or sitting on raised, stepped benches made from the same stone as everything else. Below, she heard chanting and murmurs of conversation and she walked to the edge and looked down.

At the centre of the temple was a wide hole, fringed with a low square wall of an entirely different stone, this one red like the priests’ clothing, speckled with flecks of white, gold, and black. There was a golden chain atop the wall, perhaps to stop people accidentally falling in, or perhaps for some ceremonial purpose she did not understand. From her vantage point, Flin could see that the hole went deep and was circular, with the mouths of dark tunnels puncturing the sides. The effect made her feel she was seeing a tree from within, somehow turned inside out, after being attacked by countless giant woodpeckers. The whole was lit with a flickering red glow from somewhere below, and a different, brighter light from the great lanterns hanging from many wide columns. The sun remained hidden.

The walls and columns held rough figures, the stone clearly not suited to fine carving, although each statue or relief was recognisably different, with associated carved symbols. Flin did not know what the glyphs meant, or who the carvings represented.

It was a powerful experience. She felt a little lightheaded and could not decide whether it was the walk up the mountain, or perhaps gasses from molten rock far below. As she watched, offering after offering was sent down into the volcano, as the queue snaked past, each person pausing, bowing, then throwing whatever they carried into the hole.

A loud gong sounded, and everyone stopped moving and bowed their heads, silent and respectful. To the rear of the temple, a wide pair of doors opened and a string of priests exited, some bearing an ornate platform on their shoulders, a shrouded body tightly wrapped in bandages of black, red, and white. The effect reminded Flin of the Spring Pole she had danced as a child, and she knew the work was considerable and meticulous. An image of red-robed priests doing likewise, dancing around a hanging body, weaving as they chanted, leapt into her head and she quickly pushed the thought away, to better concentrate on what she saw.

They slowly walked to the lip of the hole, feet stepping in time, movement perfected. They barely paused before letting the corpse slide off the board, those at the front of the platform lowering it, those at the rear pushing up, actions synchronised. The body fell, turning and spinning down into the invisible depths and red glow beneath. Whoever it had once been was lost to view and committed to memory.

As soon as the body was out of sight, the priests disappeared through another door and the activity in the room resumed. Flin was still feeling dizzy and sat down on a free bench, listening to the others in the viewing area. Most of the talk revolved around the reason they were in attendance—to witness family members throw in offerings, or to pay their respects to relatives or friends. To her right, however, one whispered conversation stood out, catching her ear.

‘That’s the third this moon. Each found the same way, drained, like they’d somehow been dried out without rotting. Like,’ she paused, clearly thinking what to say, ‘like salted fish.’

‘What’s The Forge doing about it? Nothing. I hear nothing but denials that its back.’

‘Exactly, they don’t want to acknowledge it, they simply ignore it. Maybe they think it’ll just go away.’

‘My mother and grandmother were talking about it, between them they remember the last two times, years and years back, when my grandmother was my age and when she was the age of my own daughter. It was the same then.’

‘Do you think the killer is the same? If he is then he’s really, really old? Maybe it’s not the same person? If it was then they really are ancient.’

‘I don’t know. My grandmother called it something else, she said it was no longer human, but something different. She said that the blood is used for evil rites, drunk. This last death, my uncle was nearby and saw the aftermath, strange symbols written in blood, bloody tracks leading away, up to the mountain.’

‘What did your grandmother call it?’

The other woman looked around, before she whispered her reply.

‘She called it vampire.’

The pair moved away and Flin resisted the temptation to follow. She was not entirely sure what she had heard, wondering whether her language skills were good enough to affect a decent translation but the last word, the word vampire, she knew. It was the same in other places, an ancient word, crossing time and language. The idea of someone drinking blood made no sense, but then she had witnessed other things that made no sense. She felt a chill, despite the warmth, forcing down fear and calming her mind once more, as she had so many times since Kadan had died.

A tear slipped free and she wiped it away. It was not the only tear to be shed in the temple.

Time to go.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the first episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Read more about my fiction here or map making process here.

If you have enjoyed this, please consider subscribing to ensure you do not miss the next chapter:

Share with those you know:

Or leave a note or comment—I always reply, although sometimes it can take a while to do so!

If you really love this story and wish to support my work in a financial manner, but do not want to subscribe, then you can also leave a tip of any amount here:

A continuation journey. Rituals removing dead and refuse. Clean up their acts. Reminds me of Easter island and burial only in caves.