Dancing With Death is the sixth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the first chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

Apart from a select few Beta readers, this particular story has not been shared before!

If you enjoy this Tale and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

Start At The End

‘You’ll want to start at The End,’ the sailor called over to where Flin was standing, on the verge of leaving the ship, thickly calloused hands neatly coiling the rope he was holding. He made it look simple.

‘I’m sorry, what do you mean?’ Flin had not expected to discuss philosophy with one of the crew of The Henray Raphial.

‘Turn down the second street past the warehouse over there, continue up the hill quite a ways, it’s there. Straight up, can’t miss it. The End. Tales say it used to be the last inn before the Maelstrom, or maybe the northern ice, but that was a long time ago. Now, it’s the place to listen to the best of you lot. Now, we bring over several Merries and Mirths every year, something about The Ribbon draws you lot to this place, and I think you’re the best I’ve heard. Now, I thinks you could make a pretty penny up at The End.’

‘My thanks, I’ll start at The End.’ She gave a short bow to the sailor, who smiled, his entire face creasing into a series of dark furrows, freshly ploughed skin, nodded back and moved away, returning to tidying the deck.

Flin was glad to be heading ashore. After three weeks at sea, each rougher and colder than the last, she had just about had enough of boats. For a while, at least. There were always new places to explore, new places to search and the waters always held and swept along new stories.

As she clambered down the studded plank bridge to the dock below, Flin again wondered what she was doing in The Ribbon and, especially, what she was doing so far north.

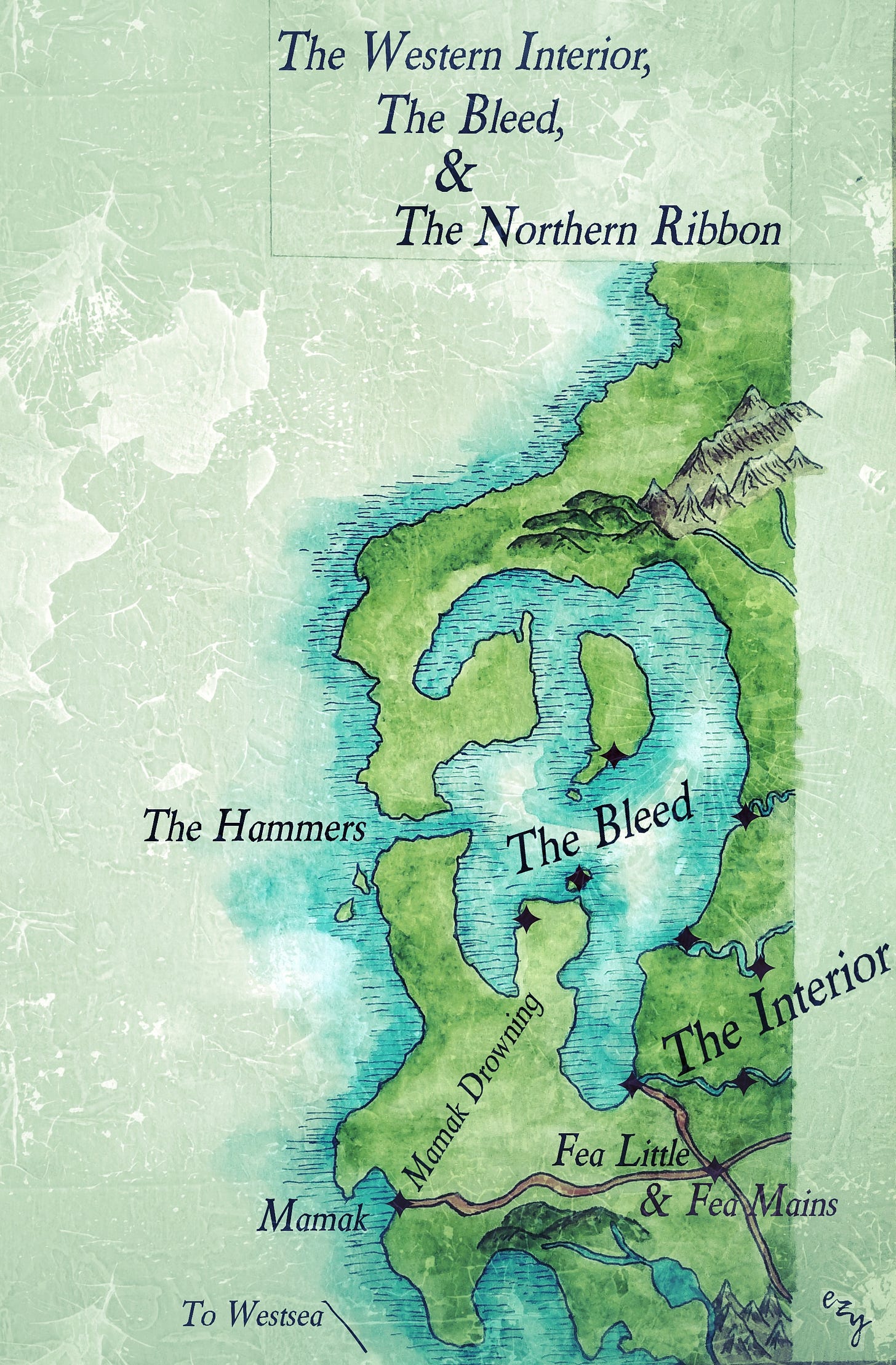

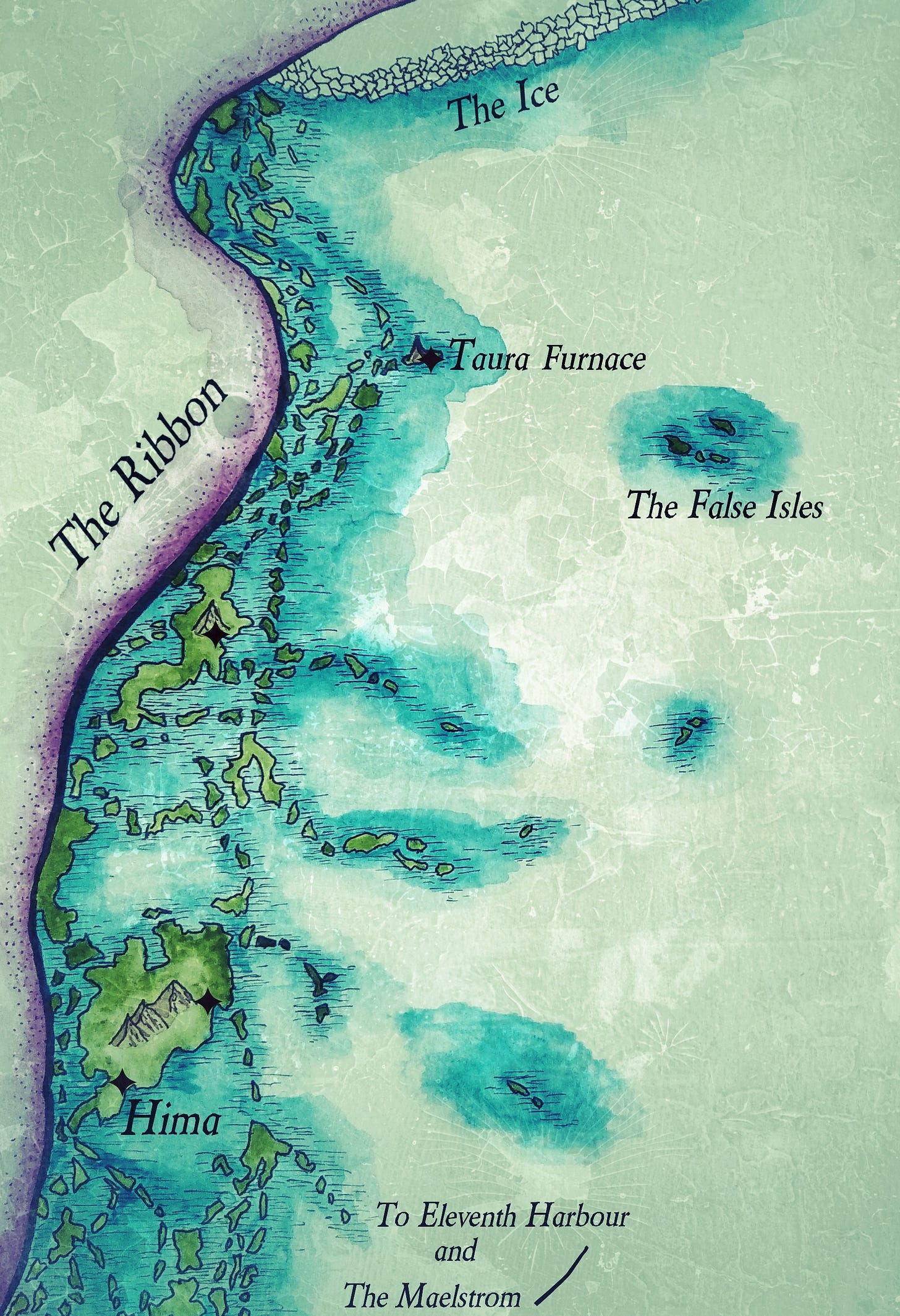

When she had originally thought of the idea, many weeks travel earlier, the logic had seemed simple but sound: start at the top, work down. Nobody knew all of the islands in The Ribbon, the archipelago stretching thousands of miles on a roughly north-south axis, beginning in ice and passing through fire all the way to reach more ice. At least, this was what the stories said. There were rumours of huge islands, many, many days’ travel across. Perhaps her recollection of home had been wrong, perhaps she had been raised somewhere out here, deep on an island which had not felt like an island? She had no idea. It would not be too hard to visit the bigger islands, try and find things that felt familiar: mountains, forests, snowy winters, and warm summers. On her travels, Flin had learnt that snow could be found everywhere, no matter the latitude; if a place was high enough, it would receive snow. It made her search even harder.

To her right another, larger, ship was being moored, a scatter of passengers on her deck, all but one looking up at the city. That lone passenger seemed to be staring straight at Flin, face hidden by the shade of a wide brimmed hat, worn despite there being no sun. She was wearing loose trousers and a short sleeved leather vest, with a battered pack slung over one shoulder and what looked like a sword hilt beside it. Swords were very rare: few bothered with something which was only ever used to kill other people—axes and knives made more sense. Even from this distance, Flin could make out swirls of tattoos running up her bare arms. She wondered why she was sure she was being stared at and paused for a moment, considering waiting for the woman, but then turned back to the city and continued walking. Anyone searching for her would not find it hard to do so. Besides, the woman had probably been looking elsewhere, her gaze shielded by the hat. For some reason, the tiny green hook Flin wore at her throat felt warm.

Dodging cursing longshore workers, sweating hauliers, hawking vendors and an array of others, Flin picked her way past a broad and relatively squat lighthouse to the warehouse to which the sailor had pointed. Everywhere she looked, the buildings were all constructed from the same black stone extracted from one of the quarries on the flank of the vast volcanic mountain which made up the centre of the island. Level and wide skirts from ancient flows, extremely fertile soils, and temperatures which were warmer than many other islands this far north lured the first settlers. Now, there was little space left for crops, the whole mountain encircled by the great port city of Taura Furnace, the docks interspersed with salt pans producing the famous black salt for which the island was renowned.

Flin knew the island was not large, but it was widely considered the best place in The Ribbon to sail into from Westsea, Mamak, or any port further north in The Drowning. The biggest settlement before the stretches of icebergs and thick winter ice was a good place to begin this leg of her search—a point on a map, a place in time—even though she knew she had not been born in a treeless place, knew she had been born somewhere lacking the scent of the sea, and certainly knew there had been no volcanoes. Those, she would remember.

‘You any good with them?’ The woman was sitting beneath an awning outside a non-descript, squat house, darning thick socks. Beside her, two men and three children were doing likewise, mending clothes from a large pile on a low table between them. She pointed with a jerk of her chin at the instrument cases hanging from Flin’s shoulder, beside her rolled blankets, water bottle, haversack and cooking pot. She needed to get a proper pack again.

‘Yes. Very.’ Flin had long learnt it was best to answer truthfully. She knew she was good, ‘I also sing, tell stories, lead dances, make people laugh or cry.’

The woman nodded silently in reply.

‘I was told to start at The End. Am I on the right path?’

‘You are, you are,’ she paused in her sewing and looked at Flin carefully, eyes flicking to either side of them, up and down the street. ‘Listen Songstress, be careful here in The Furnace. Things are not as safe as they once were. Things happen here, every generation or so.’

‘Do you mean danger?’ Flin replied, unsure of the woman’s exact meaning, some of the words unfamiliar. Although she picked up languages fast, she had only been learning the main trade tongue of the northern Ribbon for slightly longer than the length of her voyage: lessons, meals and passage given in exchange for entertainment every evening.

‘Danger, yes. But more than that, I mean,’ the woman gestured, clearly frustrated that she had no other language to fall back on, ‘I mean danger from the other, not normal, not even real like you or me. Not human. You understand?’

Flin frowned. She thought she knew what the woman meant—a supernatural danger, something Other. She shivered a little, despite the warmth.

‘Yes, you do understand. Just be careful, don’t head out alone at night. This city is on edge right now, Songstress. I would say don’t draw attention to yourself, but I guess that’s what you do? Good luck, you need anything mended, you know where to find us.’

‘My thanks.’ Flin nodded and continued uphill. Wherever she voyaged, wherever she searched for home, she found people spoke to her, told her things they would not volunteer to other travellers. It was one of the benefits of being a Merry-Mirth, people knew you always meant well, brought joy and raised spirits. When they weren’t trying to rob you of your earnings, they were extremely welcoming.

She walked up cobbles glistening with recent rain. The weather here was grim, something everyone she had spoken to before arrival had agreed—if it wasn’t raining, it was foggy, if it wasn’t foggy, then the winds were trying to blow you to the pole. The pair of locally-born sailors she had managed to quiz on the subject had agreed, summer in Taura Furnace was swift and still windy, but at least if you could escape the gales it was always warm, thanks to the volcano. The streets steamed gently, but there was no sun, heat bounced from the road and off the walls around her. It felt odd, like being in a steambath fully clothed, drifting towards a heady, damp sleep, with sudden, occasional blasts of icy air to wake you.

Flin walked past other shop fronts offering a wide array of goods and services. She saw cobblers and tailors, bakers and fishmongers, cutlers, potters, glassmiths, cabinetmakers, upholsterers, and even a shop dedicated to the rare craft of writing and reading. Everything was here, everything you ever thought you needed, and a thousand other things you did not, was either imported or made in Taura Furnace. Raw materials and basic goods arrived in the city: leathers, skins, great whales, woods, fabrics, glass, horn, bone, ivory, gems, even gold and silver; all transformed by a host of crafters and creators. Their goods were then traded out to the cities and towns further south along The Ribbon, or taken across the sea to Mamak, or further south to the Isthmus, and beyond. Even the rich, fertile soil had once been traded, dug out and shipped to other, rockier islands, until the local leaders had put an end to the trade when they realised no soil meant no fresh vegetables, no fresh salad crops, and no fruit—grain and other dried staples could be imported, but fresh, green plants could not.

In the time since the Great Canal between Eastsea and Westsea had become unnavigable, the trading power of Taura Furnace had grown exponentially. What had been made in Eastsea was now made here, then sent on a long journey, to arrive in the tower markets, available at a much higher price than before. Items which would be incomprehensibly expensive in Eastsea could be bought here for a fraction of the cost, making small scale traders rich once, or if, they made it across the Isthmus or from Mamak and onwards, through Fea Little. In recent decades, the journey had become exceptionally dangerous, pirates, raiders, and bandits proliferated, often effectively blocking routes for weeks or months at a time. For those who risked the journey, the rewards were high, but the potential cost could easily include their life.

Flin needed little, but the idea of upgrading her worn clothing, buying new strings for her fiddle, spare pegs, a new bow, maybe even a better blanket, was tempting. After freezing on the Henray Raphial, thicker socks seemed a good idea too, and maybe new underwear. She had long ago learnt that, when you could get it, new underwear was always wise.

As she walked, she marvelled at how everything seemed jumbled together: a butcher beside an apothecary, a chandler to the left of a rug merchant. She assumed the tanners, blubberhouses and slaughter yards would be somewhere else on the island, somewhere their smell could be blown out to sea. Most cities had streets where shops of the same ilk clustered together, but not Taura Furnace, here, everything was dispersed.

For Flin, learning about a place was important, and she always paid attention. It added layers and details to her own stories, those she made up entirely—if she recognised an accent in a crowd, or a word spoken in a language from somewhere she had visited, it made sense to slip in real facts about a location, change where the story was set to hook the audience, before reeling them in with fantasy and tales of adventure, love and loss, yearning, treasure, or despair. It nearly always worked, adding extra coin to her purse, longer laughter, or more sincere tears.

The End was exactly as Flin had imagined. Taking up the whole corner of a street junction, it stretched in two directions, uphill and sideways, with a wide and tall gate she guessed led to a courtyard. She wondered if they had stables, there seemed little need for horses or ponies on such a small island, at least not beyond haulage purposes and perhaps public transport. To keep such a beast on an island with precious little natural plant cover seemed foolhardy and she had only seen one pair of small, hairy ponies since she had arrived, all other traffic seemed to be on foot, or pushed or pulled by handcart.

She stood still for a moment, looking at the building from across the street and catching her breath after the steep climb. The cobbles were bright, the glare forcing her eyes to squint, despite the lack of direct sunlight; this island was odd, the weather even stranger. People passed by, barely glancing at her, some wearing some sort of wooden eye-ware she guessed cut down on the glare. The inhabitants and visitors in Taura Furnace seemed as diverse as the shops and businesses she had passed, with many styles of clothing, different hair, different tattoos, languages, and a wide variety of colours and shapes. There had even been three Abriki down by the harbour, as well as several Seafolk, and two short, hooded people who vanished before she could catch up to them. She was sure they were Tanuthian, and she longed to ask them more about their underground world. A chill ran down her spine and she felt a strange flutter and stabbing pain in her chest, as she always did when she thought about Youlbridge. She twisted a hair around her finger and forced her thoughts back to the inn in from of her.

She counted three storeys, with extra windows in the sloping roof and small, barred windows at ground level, indicating a cellar or basement. Five floors was a very rare and rich establishment. Most inns she had visited were lucky if they had a set of stairs. Usually, all Flin would find was a ladder to a shared loft, space allocated on a first come, first served basis, sometimes with straw pallets, other times simply bare wood or a covering of rushes. She had stayed in other inns where there were comfortable bedrooms, sometimes even individual, unshared, beds and she guessed The End was one of these. If she could play here, it could prove a very comfortable stay.

The sign hanging above the broad, red-painted door showed a rough sea, with a stylised version of the inn standing alone on a rocky headland, the volcano looming above, red lava flows streaking its flanks. She crossed the street for a closer look. Above the red door in the picture she saw the same sign, painted in miniature. A repeating idea, each smaller and smaller, onwards into infinity. It seemed a strange touch and, for some reason, made her feel a little uncomfortable.

‘Come in,’ the voice from the street behind her made her jump. She had not heard the man approach, ‘I am Albin and this is my mother’s place.’ He walked to the door and waved Flin closer. ‘We are always keen to add to our entertainment bill, but then you must already know that if you are here. Come, come in.’

Flin followed the man, Albin, through the door he held open with his hip. In each arm he carried a large basket, each brimming with produce. She wondered whether the cuts of meat or the vegetables had been brought in by boat, or raised or grown somewhere on the island. The nuts had certainly been imported—there were definitely no trees on Taura Furnace.

If the sky was ever to clear she knew she should be able to see the great chain of The Ribbon to the west, to the north and to the south. Tall peaks, pounding waves, an unknown number of islands disappearing into the great ice sheets of the north, or the vast ocean of the south. The sailors had told her the nearest islands were scant hours’ sail away, given good winds or a powerful galley and, the further into the chain you went, the less windswept and barren the islands became.

Flin was about to close the door when a tremor ran up through her feet, the wood vibrating beneath her hand. Birds shrieked and leapt into the air everywhere she looked, dogs howling from every direction.

‘Come in. It’s just Taurie; she’s grumbling about the change of weather. Come on, The End is solid, well-built, we’ve stood here for centuries and it’ll take more than a little shaking to dislodge us.’ He smiled and Flin smiled back, giving the streets a last quick glance before shutting the door on the cacophony outside.

The man she followed was not tall, nor was he short. He was neither fat nor thin and Flin had to look closely to see what colour his hair was. She had met such people several times on her travels, they could pass unnoticed in any room, passing no comment and gaining no attention. It was a peculiar thing and, in the right circumstances, a useful gift. The last such man she had met had tried to kill her—which had certainly gained her attention.

‘Here we are. Tell me, who may I say is here for an audition?’ he asked, laying the baskets on a scarred table.

Flin realised she had so far not said a word to the man and smiled at him, launching into her prepared speech. She knew she would get better at the local language, she always picked up new tongues within weeks, but it was always wise to have something ready.

‘My name is Flinders Jeigur—Flin. I can play my fiddle or flute, my drum or kora, and any other instruments you can hand me. I can sing, fast and slow, joyful or melancholic, I can lead dances quick, and dances tender, in groups and lines, circles, singles, or pairs. I can tell stories comic, epic, folk, or my own, I jest, I share the news, I weave a web of my own travels and ways. I make people laugh, I make them weep, I make them gasp, never let them sleep. My tutor was Rharsle Tren the Eloquent and...’

‘Rharsle Tren the Eloquent?’ The new voice came from above, descending the wide stairs to Flin’s left, ‘Now that is a name I have not heard in years.’

‘You knew Rharsle?’ Flin asked, smiling widely. This was not the first time she had applied to play in an inn, only to find she was walking in the footsteps of the man who had taught her, the man who had paid gold to take her from her family. It always gave her hope that she was on the right track, that she was heading home.

‘Oh yes. Back before Albin here was born, Rharsle spent a winter in The End. We got on very well. He was captivating, could enchant a crowd better than almost anyone else I’ve ever met, before or since.’ The woman reached the foot of the stairs, ‘I am Ana, I am lucky enough to run The End. Come now, let’s head into the smaller taproom, it will be empty at this hour, and we can talk, eat, and listen to you.’

Flin nodded and followed the woman, who gently patted Albin on his shoulder, thanking him for bringing the food and finding Flin. He smiled in reply. It was clear this was a happy household which, in Flin’s experience, meant the inn would be a good one. Happy staff and happy owners meant a happy ambiance. She relaxed for a moment, just a little, then remembered The Maze Fighter and Sarah and Mariea. Again, the memory of Youlbridge brought a sharp pain in her chest and she turned her attention to Ana, concentrating on the details, pushing the pain away.

Ana was the opposite of her son—where he was invisible in a crowd, she stood out. Her thick, lustrous hair was arranged in complicated braids and twists, piled atop her head and sporting several ornaments and exotically coloured feathers. Although lighter than Flin’s, her skin was still darker than that of her son, making piercing green eyes stand out from a face which had held enough smiles to leave a trail of their passing around her eyes. Where Albin was of an average height, she was short, although her hair made her feel a more imposing presence, as did the way she moved, confidently, in control. It was clear she was someone not to be trifled with.

Flin laid her bags and coat on a table and joined Ana and Albin at another. Ana rang a little bell on the wall, ordering some tea and toasted bread and jams from the young woman who entered, listened, nodded, bowed, and left without a word.

‘That was Omena, she doesn’t say much, but I’ve never known her get an order wrong. Now, tell me, how is the old fox Rharsle? I miss him.’

Flin drew a breath, this was a conversation she had experienced more than once, and it was never easy. In her life, talking of death was always either the death of Rharsle, or a death in a song or story. She had never known anyone else long or well enough. In some ways, she liked this—she did not know which friends still walked the earth, and which had returned to it, and each lived on in her memory. Her son, Kadan, was the sole exception to this rule, and she never spoke of him.

She took a breath and told the story, her story, not the whole truth, but a version of it. Throughout the telling, Kadan remained a constant presence in her mind.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Read more about my fiction here or map making process here.

If you have enjoyed this, please consider subscribing to ensure you do not miss the next chapter:

Share with those you know:

Or leave a note or comment—I always reply, although sometimes it can take a while to do so!

If you really love this story and wish to support my work in a financial manner, but do not want to subscribe, then you can also leave a tip of any amount here:

Tis an hour prior to midnight. Taken me many weeks to reach this space to start another journey with you Alex. My eyes now are a bit cloudy but I will try to read and make a few notes. Must be a glare to need wood protectors for the eyes like in the arctic circle. Not to have protection can cause blindness.

Was delighted to see this land this morning 🙂