Snatched Away in a Blink

Death In Harmony: Part Twenty-Seven of Twenty-Nine

Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the twenty-seventh chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

Snatched Away in a Blink

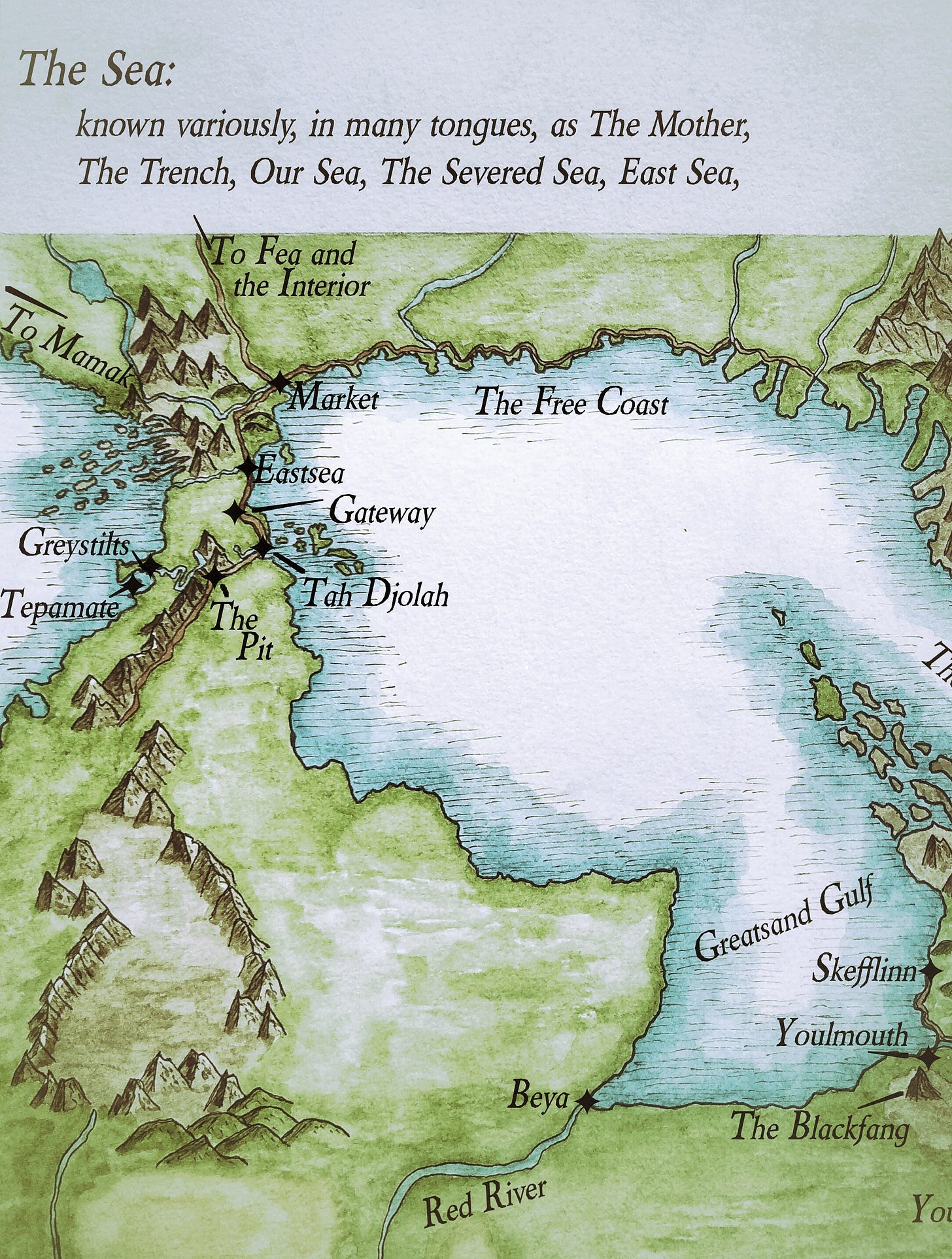

The Past: west of The Templelands

After changing his moss and feeding him, Flin changed Kadan’s clothes, for the first time since they had descended into the darkness below Youlbridge, all the while talking to him softly, singing snatches of song, and whispering of all they would do on the adventure ahead.

‘We will rest a short time longer, then try and make our way up cliff and on to the north road, see how much ground we can cover before the sun rises. I think night time travel is safest, as she said.’ There seemed little reason to deny the fact the woman’s advice was sound, even if she had then followed it by vanishing before her eyes, even if, just a short time earlier, she had wanted Flin dead and Kadan taken—sense was sense, and there were precious few other options available, and none of which as viable.

After eating the rest of her food, Flin made another tea, drank it, then quickly packed to leave.

There was still plenty of time before the dawn and the nearly full moon would light the way, despite the veil of smoke still hanging between the mountains. The wind must had shifted a little, as she could smell the burnt, or perhaps still burning, city. She hoped the fire was out, hoped Youlbridge was saved, thinking how hope was an odd thing—it was only ever extinguished itself when people chose to let it be so, its flame would never die unassisted.

Flin kept to her own hope and regularly fanned its flames. She kept to the surety that she would escape with her baby, that they would somehow find her home and return to the mountains, valleys and deep forests she had known as a child, play with Kadan in the summer pastures, gather berries and watch eagles soar beneath them, while the fat marmots called above.

It would happen; she held to hope.

‘Let’s go, little one, time to walk once more.’

The trail they followed was not too hard to see, even in the night. Despite risking the bowstring to the damp, Flin kept it strung, two arrows held in the same hand that held the bow. She would not blunder into any threat unprepared, not again.

The woman’s directions were precisely as described and it did not seem long before Flin stood at the edge of the woodland, looking out at the road passing by. To her right sat the town of Alvidra Falls, where the bridge crossed the Youl, which then disappeared down the famous waterfalls in thunder and spray; to her immediate left, the road stretched behind her, back to Youlbridge. The other part of the junction led to the east, to her left, and the Templelands.

Before leaving the trees, she cut a thin hazel staff, with a fork at the top where she could rest her thumb. The bow was strapped to her back, beside the pack, blankets, and the bundled coat she had taken from the man who had tried to kill her.

To either side of the road, the trees had been cleared for a long bow-shot. Here and there, small structures and walls loomed out of the dark, various barns, sheds, troughs and folds showed the area was used for livestock, or crops, or both—yet she heard no sheep, saw or scented no cattle. The area was deserted.

The sky was clear, with the brighter stars shining through the light of the moon. The earlier clouds had cleared and Flin realised she could no longer smell smoke on the wind. Whether this was because she was too far away, or whether the fire had stopped, she did not know. The moon was bright and, out of the trees, showed more than enough for Flin to guard where she walked, where she placed her feet.

As she walked, Kadan strapped to her chest, the staff helping with every step, she realised she was following others. Many, many others. She saw no one, but the roadsides were strewn with odd items. Here, a small chest, burst open, sheets and cloth strewn around like angry, deflated ghosts; there a large wardrobe, standing neatly, as though the owner had decided to rearrange their furniture in a somewhat extreme fashion. There were other things, small items and larger, a whole cart, one wheel in pieces, bundles of clothing, rugs, sheepskins, an anvil, embedded on one side, deep into the mud by the road, a woven wicker ball beside it.

She paused, contemplating taking one of the sheepskins to use to sleep on, but decided she was already carrying too much weight. Her woollen blankets, coat, and cloak would be enough. Before she started walking again she bent down, the moon reflecting off a scrap of fabric and catching her eye. It was a small ribbon, no longer than her hand span and folded over in two. The material was expensive silk and, as she held it, she realised it had been owned by a child, two matching places one either side demonstrating where it had been pinched between thumb and forefinger, rubbed together for comfort. Somewhere, ahead on the road, a child would perhaps have had difficulty getting to sleep, missing their ribbon.

Flin put it in her pocket, and continued, a little saddened, the weightless ribbon heavy inside her coat.

She followed in the footsteps of those fleeing plague, running from rumour and death, hoping to find a safe place somewhere in the Templelands, perhaps with relatives or friends, perhaps as a refugee. On her travels with Rharsle, she had seen similar roads, similar detritus, broken and sad figures trudging through the hours of day, sleeping in ditches or under scraps of unsuitable fabric. It was always the same, with those who fled disaster carrying too much and taking the wrong things: their grandmother’s intricately-carved sewing chest, a heavy tapestry which had been in the family for generations, an ornate wardrobe. Disaster did not care who it made refugees, it did not care that they were forced to leave, forced into choosing what to take and what to eventually reject, sometimes only after the damage was done—the extra weight breaking their cart, laming a pack animal, or worse.

Disaster just was—it did not care.

Flin suspected the Templelands would be more welcoming than many other places she had seen. After an earthquake had destroyed one town, the next had refused entry to the hungry thousands, after famine and locusts had ripped through a harvest, those fleeing and searching food had been stoned and forced from the road.

Disaster just was, it did not care and, in her experience, neither did people. Better to protect their own, why feed a stranger?

‘Because,’ Rharsle’s voice travelled across the years, when she had argued the same, trying to find the right in what she had seen, to justify the actions of a violent crowd, ‘one day, it might be them who needs feeding. It might be them who needs a roof as the snows fall and the ice bites. There are places where hospitality, and the respect of a stranger, are still held in high esteem, places where we are all safer as a result. One day, everyone might lose everything. Anyone lose anything. Remember that, Flinders, remember that we could easily have all snatched away in a blink, a click of the fingers.’ He snapped them in front of her face. ‘You are lucky, your skill with music and song and story should be able to feed and clothe you, no matter what. Others are not so lucky.’

Flin walked on, thinking about the movements of people, nearly always humankind. Why was it that the other Talking Races did not seem to throw out refugees? At least not that she had witnessed.

Beyond the cleared space, beyond the fields and low walls, the forest loomed and followed, keeping pace with her every step, a dark comforting presence. Flin had always felt at home in the trees, felt protected by them, rather than lost and in danger. Several times, when she thought she saw movement ahead on the road, she thought of running to the relative safety of the tree-line, but held back. Here, a stray dog digging into a mound of fresh earth marked with a simple stick marker. A child-sized mound of earth. There, an owl, taking off from the ground, where it had swept down unseen and unheard, to snare an unwary mouse. The dog growled at her as she passed, hackles raised. It was thin and hungry and mean. She gave it a wide berth and it returned to its digging.

Flin felt like a mouse, she felt that there was always something above and behind her, ready to come down and take her life or snatch Kadan. Her fear was not as great as it had been, but she still knew all could change on the turn of a heel, or the drop of a hat.

She could not stop thinking of what she had seen, of the woman, of the monsters, of the men she had killed. For some reason, she thought most of the lion, of her deception, her laughter and scream. She had felt utterly helpless at that point, totally drained and accepting of death, at peace.

Flin walked further and began to see small camps, off the road, mostly at the halfway point to the forest. Most people feared the trees, feared what lived in them, but they also knew they were not safe from other travellers. Instead of hiding in the woods, they had pitched their makeshift tents, awnings, and tarps just far enough away that they thought they would be invisible in the night. Before the moon had risen above the mountains, they probably had been.

There were no fires, but she did see people still awake, protecting their family as best they could. She knew that, the more nights that passed, the more distance they walked, the less this would happen. Sleep would claim them, exhaustion would overcome their protective instincts, the adrenaline would wear off. Then the wolves would strike but, in her experience, it was never actually wolves, but other people.

As though her thoughts had summoned them, she felt a drumming of hooves, first through her feet, then echoing within her ears. They were somewhere behind her on the road, getting closer, fast. Many horses moving swiftly through the night was never good news, and Flin cast around for somewhere to hide. There was nothing perfect but, as luck would have it, another wardrobe—the third she had seen—stood off the road, one door held at a wild angle by a single hinge, the other still closed. It was not ideal, but it would do, and she ran to the shadowed darkness within, finding it lavender scented and surprisingly warm, pleased she could easily fit within, even with her pack on. She left the open door as she found it, crept into the darker side, and waited, heart pounding, mouth dry. She was sick of fear.

From her hiding place, she could see a small encampment on the opposite side of the road, a simple three sheets strung around a cart, a large carthorse standing off to one side, head down, one hoof slightly raised. At that distance, the silvered moon shadows were deceiving, but she watched as the drumming woke someone in the camp, who then woke the others. She could just about hear frightened voices, trying to be quiet, but terror and despair raising their volume, the chamber of the wardrobe catching and amplifying but distorting the words. The urgency in their tone was not enough; Flin knew they were hastily discussing fleeing to the forest but, by the time they fell silent, all standing huddled in a group, it was too late.

There were around ten of them, although Flin could not be precisely sure, perhaps twelve, cantering towards the group, wearing the uniform of the Youlbridge Guard. They gave the people no chance, barely slowing, their horses smashing into fleeing bodies, trampling them where they fell, curved swords, lances, and spears doing the rest. Men, women, children, all dead.

It was over quickly, screams silenced, moans cut off, lives ended. The horsemen regrouped nearer the road, controlling their mounts with their knees as they cleaned weapons, checked edges, several taking pulls on flasks, eating handfuls of food from pouches, resting the horses for a time and all the time talking quietly amongst themselves like any other group of workers, just doing their job.

Kadan slept, and Flin prayed to every God she had heard of that he stayed asleep.

She could smell the horses, catch tendrils of the tang of coppery blood, hear the Guard openly complaining within earshot of their commander. They wanted to go back to the city: they were tired and worried about their families, their homes, the patrol had been long enough already.

Yet they also had their orders and continued to prepare to follow them. As she had heard before, in other languages and other places, the Guard always loved to complain, no matter the situation.

Some of them dismounted to urinate, squatting or standing by the roadside, but one of the men walked directly to the wardrobe. Flin resisted the urge to scream, sure that her pounding heart would be loud enough to hear, that Kadan would wake, or that he would simply look inside.

She lost sight of him, but heard his stream of piss against the wood beside her, could smell the remnants of whatever spiced food he had eaten earlier in the day. Her hand crept to her knife, knowing she would stand little to no chance, but preparing to fight nevertheless. Her armpits were once more wet with sweat, her thighs clamped tightly together, muscles tense.

‘We go on, clear as many of these as we can before dawn.’ The woman who spoke was clearly in charge, perhaps their Sergeant, ‘You know we cannot risk being seen to do this in the day; and look, I don’t want to sleep out on the road any more than you do. How about this? By first light, we will be on our way back to hot food and warm beds in the barracks at Alvidra Falls.’ The announcement was followed by a chorus of appreciation. ‘Now, let’s go. Natt, put that poor excuse for a cock away and saddle up.’

The others laughed and the man who had urinated against Flin’s hiding place walked back into her field of view, his back almost within touching distance. Flin held her breath.

‘Sure Sarge,’ he said, beginning to turn towards Flin, ‘Just let me kick this over and…’

‘Now, Natt, mount up and ride, or I’ll personally kick you over and piss on you. We ride.’

The man grunted in reply and was swiftly back in the saddle, and the whole patrol moved off at a trot.

Flin waited, too scared for a time to move out of the wardrobe, shaking and feeling deeply sick. Then, she stepped outside and threw up, waking Kadan in the process.

The Guard were supposed to protect, and she knew the saddest thing of all would be that these men and women would have been told they were doing precisely that—protecting others by killing anyone fleeing with potential plague. She knew they thought they were doing the right thing, that they thought the alternatives would have been worse, or more dangerous. Refugee camps bred disease in their squalor, and letting those bearing the plague run elsewhere risked retaliation from others.

The route to the Templelands would be even more dangerous than she had thought.

As she listened to the hooves disappearing, wiping her mouth and trying to calm her breathing and heart, she decided on the best course of action.

‘We go to the woods, little one, we stay within the trees. Horsemen won’t go in there, at least not far, and not at night. Too risky for their legs.’ She looked across at where the encampment had been and briefly considered taking the horse, still tied in place, but now very much awake and straining at its bonds, ‘No, too easy to track, too big a target, too risky in the woods.’ She took a mouthful of water and swilled it around her mouth, before spitting it out and swallowing another, ‘Let’s go.’

Kadan looked up at her and then closed his eyes, quickly falling back to sleep.

The distance to the trees felt a very long way indeed. Flin passed the small camp and tried not to look at the shadowy mounds on the ground, some far too small. She did not need to check the camp for anything, she was well supplied and prepared for a long journey, with plenty of money and food, but the habit was tough to push aside. One man’s waste or loss was another’s treasure.

Once she reached and entered the shelter of the trees, it did not take long before she found a trail running parallel to the road. Maybe it was used by deer, maybe it was used by those who did not want to encounter the Guard but, either way, it would still be safer than the road itself. Here, she could run and hide. Here, horses were useless and arrows less likely to find their target.

There was just enough light to see by the moon, the canopy allowing shafts of pale silver to fall here and there. Flin noticed the forest cover itself was more sparse than was natural, and Flin guessed it was regularly visited for lumber, for cordwood, for scraps for the fire, fungi, nuts, berries, and medicine. The forests of the world, no matter where she had travelled, were all used in the same way: grocery, apothecary, and builder’s yard, all in one. But only so far, only so deep.

And there was good reason for this.

The forest, during the day and visited in numbers, was full of friends, a place of gift and reward. At night, however, it could be a very different matter. People did not normally enter the deep woods alone, and certainly not after dusk. There were reasons for this, reasons that each human village and every town and city had rules and regulations about how far into the woodlands their residents could hunt, or gather, or fell. There was a reason many places had barely grown in generations: expansion at the expense of forest cover was simply not an option.

People believed the Gods protected the forests, Flin knew, no matter where she had travelled, it was the same. Sacred places, with vast, ancient trees, were home to others, full of life behind every trunk or leaf. When she had been a child, her father had shown her the leaf of a gnarled and twisted oak, its crown white and stag-headed, the branches beneath still healthy and vibrant. He had explained how much life was within this one tree, how this could be multiplied many, many times over, within eyesight alone. He had talked of the cycles of growth, shown her the loam and the decay below the tree, the places where squirrels had buried acorns, then forgotten about them. The leaf had been home to something eating it from inside the structure, a freckling of galls, some sort of powdery mould, a caterpillar, and a tiny spider. And she was sure she had missed something.

Flin had spent the rest of the day climbing the branches, examining every leaf she could, every crevice of bark and every hollow. She counted until she ran out of numbers, and counted still. Every child she had known had been given the same lesson, shown how much life was there in the woods, and taught of respect at the same time they were taught how to use it as needed. The key was balance—push too far one way, and the Gods would come to punish.

Later, she had learnt more of the other Talking Races who made their homes in the woodlands of the world: the Twigs, whose tiny prints she would search for in soft mud, the tall Forest People, the slow and gentle Herders, the Bearmen, and others, some mere whispers of legend, some tales to scare children—the Great Witch at the centre of her thorny labyrinth, the Lost Child, the cannibals, the feral tribes, and more. She was not sure she believed in the Bearmen, or that there were those who ate trespassers, but she knew the stories nevertheless.

‘We’ll still be safer here, rather than out there on the road,’ she whispered to Kadan. ‘Still lots of time to cover some distance before we make camp, and I want to be as far away from,’ she paused and gestured, ‘from them, as quickly as possible.’

She looked back through the trees once, but could barely make out the open space, let alone the bodies strewn around the cart, cooling in the chill of the night, all traces of their life leaving them as nothing more than decaying meat. She kissed Kadan gently on his head, ‘Let’s go.’

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.