Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the twenty-sixth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

Dark Places

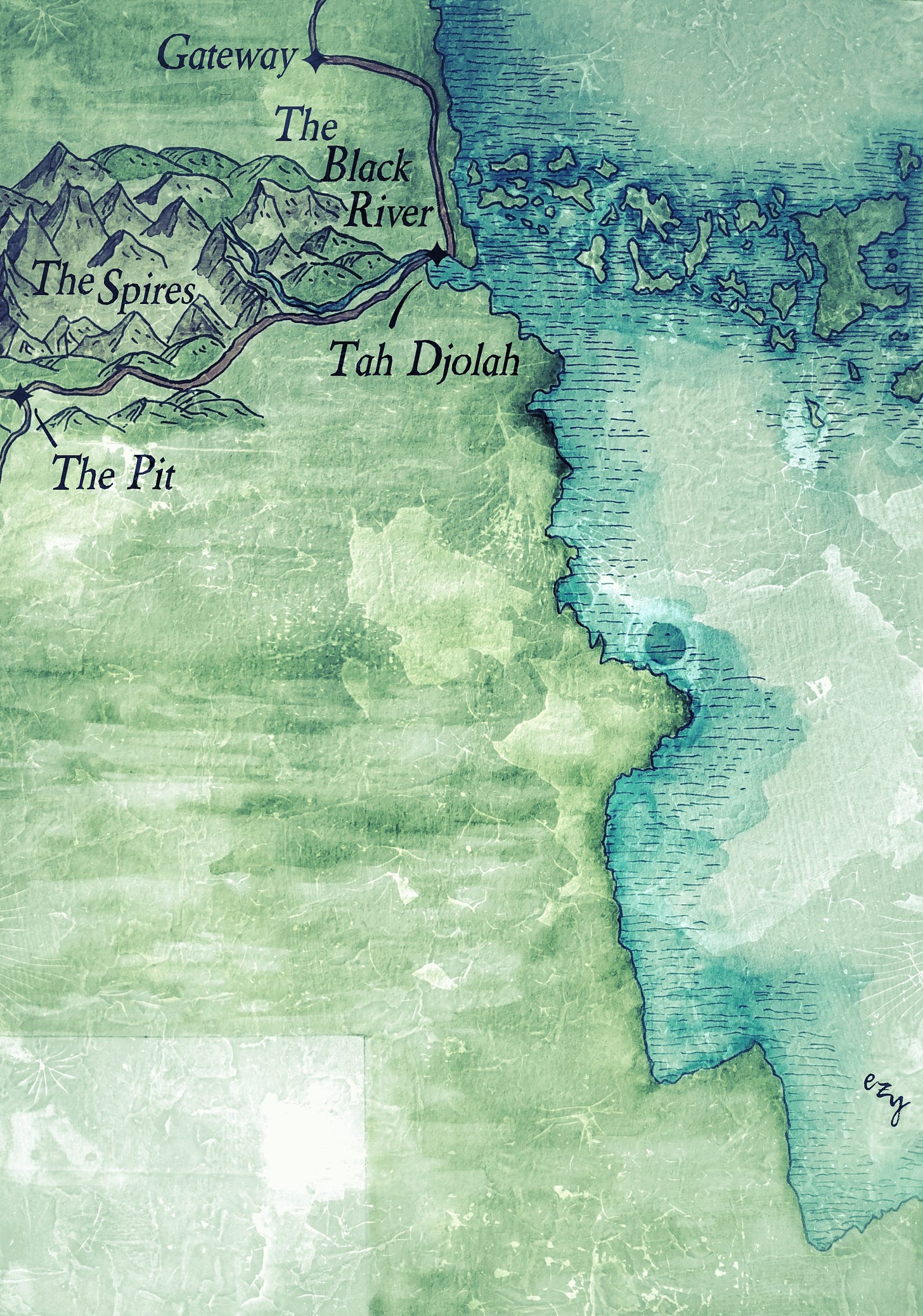

The Present: somewhere north of The Pit

‘There is another way to the top,’ the woman said, finally.

They had been silent for a time, laid on the ground catching their breath, recovering. Flin sighed, loudly and long and sat up.

‘How? Where?’

‘There are two other entrances into this valley. One is on the other side, to the west. It’s a waterfall which looks treacherous, but is actually a series of natural shallow steps and the grip is really good, despite looking slimy and slippery. This is how some of the animals get in and out.’

‘And the other way?’

‘Harder, hidden, and dangerous. But also closer to where we need to be. When we found it, we removed the last of the stair you descended, made sure we secured our front door.’ She stood and winced, stretching, ‘I’m getting too old for this. Come on. Let’s go and get it done.’

Flin also stood, also stretched, and also winced. She hurt all over: her hip was burning, her cuts itching and sore. Most of all, however, she was simply exhausted; it had been a very long time since she had felt truly rested.

‘If you decide not to kill me after this, can I sleep for a whole day, please?’

The other woman looked at her hard, then surprised Flin by smiling.

‘Assuming we don’t kill you, I’m sure my friend would be more than happy to look after the baby for a day while you slept. Now come, I want this to be over, then we get to decide what to do with you.’

They moved quickly through the forested ruins, the woman following trails she clearly knew well, and Flin following closely. Twice, they paused, listening carefully, but each time Flin had no idea why they had stopped. The second time this happened, she explained,

‘There are more dangerous things than aurochs here. Daytime is usually safer, but it is always best to check.’

After that, the warm sun seemed to cast a lot of shadow, dark places that Flin’s imagination populated with lions, with bears, leopards, Soultakers, cannibals, giant snakes, Twigs, the Forest People, and the angry, vengeful dead. In her experience, it was better to imagine the worst, then be pleasantly surprised when it failed to materialise and kill her.

As they walked, Flin realised her head felt clearer, her thoughts sharper than they had been for a while. Having someone to talk to, someone who was not going to immediately kill her, helped.

The woman stopped again, and motioned ahead at a fallen log.

‘We need to go around, this is another of our rude welcomes.’ She gestured at what Flin initially assumed was simply a dead standing tree, before she noticed the carefully placed and hidden ropes. She still could not see the trigger, even knowing there was a deadfall there. From their size and placement, it was clear the two logs would smash together with terrifying force.

The pair reached the cliff faster than Flin had thought they would. They appeared to be further south of the stair she had taken earlier in the day, what seemed a lifetime ago. Here, the trees and undergrowth stretched right to the stone, thick and dense, seemingly trying to escape up the rockface, with plants, shrubs and even whole trees growing out of cracks and fissures, vines and creepers wrapping all.

There was no way Flin would have located the door on her own, it was simply impossible to see, even when she was standing almost upon it. A veil of cascading ivy covered a shadow, which was just like all the other shadows, only it wasn’t.

‘Here,’ whispered the woman, ‘Let’s go in carefully. We try to discourage things from sleeping here, but sometimes they are stubborn.’ She pointed to a pile of scat near the entrance, which Flin guessed might have been from some sort of bear. It was mostly full of the stones of fruit, but there was enough hair matted within that she knew whatever had deposited it also ate flesh.

As they entered the dark, Flin realised she had no idea how they were going to see, and her memories of other dark, unlit places threatened to overwhelm. She took a deep breath but, before she could voice her fears, a spark, then a bright lantern flame lit and warmed the interior, dispelling shadow and flooding all with light.

‘That way,’ the woman pointed to Flin’s right, ‘there is a tunnel which takes you back into the city—that’s how we found this place. But it’s not stable, and there are a couple of places where it could collapse at any moment, which is why we were very happy to find this entrance.’

Flin looked at the steps heading down, then lifted her gaze and studied the space she stood within. There were three other exits to the round, domed chamber: two were door sized hollows, leading into wells of shadow at either side of the space, the third a stairwell leading up, carved into the far wall of the room. There were carved glyphs beside each shadowed exit, images and pictures neatly spaced between lines cut in an ancient and forgotten alphabet. The stairwell had no such carvings.

One image, to her left, she recognised, a taller figure among shorter, each of whom was dressed identically, her memory of the Tanuthian filling in the detail of the clothing, the chisel end on the tool they carried, and the shape of their faces. Another showed seven humans standing opposite seven others, the groups dressed differently, strangely. She started to move to look more closely, but the other woman turned, blocking the lantern light from the images, then placed it on the ground, as she strung the bow. If Flin survived, then there would be time to look more closely, time to examine and piece together stories and song. If she survived.

‘I assume we take the stairs?’ she asked, once the woman was ready.

‘Yes. We haven’t gone very far down the other two tunnels, after finding a much neater and technically beautiful trap than our crude efforts. One day, maybe, once we can figure out how to disarm the trap, then we might have a better look. Come on, I hope your legs are still strong—it’s a long climb.’

She led the way, lantern held low in her right hand, illuminating the steps in front of her and those in front of Flin. Her other hand held the bow and the remaining two arrows.

The spiral lead up and to the right, carved from the rock itself, with a central, solid core as wide as Flin was tall. It was was impressive and old, very, very old, each step curved in the middle, where many feet had worn away the stone over the years.

‘Does this go all…’ she began, before being interrupted.

‘To the top?’ the woman paused the climb, turning slightly to face Flin below. ‘Yes. Look.’ She pointed to the walls, where Flin could make out shadowy carvings, similar to those in the chamber below. ‘This was not a stair to get to the top. It was a stair to go down, to the chamber and tunnels below. The tunnel into the city is newer, and I suspect this stair was repurposed after the city fell, before being forgotten again. There are places where the steps have been repaired, so watch your footing.’ She drew a deep breath, panting slightly, ‘Now, let’s keep the talking to a minimum, there are a lot of stairs to climb.’

Around and around they climbed, Flin using the wall to steady herself on more than one occasion, feeling where ancient carvings told tactile tales beneath her fingers. They passed a place where the original stair had crumbled and been replaced with fresh steps, barely worn and neatly added to the existing stairwell. She wondered if the stones had been carried up, or down. Either way, it was a considerable undertaking.

Her legs began to burn, then shake. The thought that they would have to descend, assuming all went well at the top, made her knees feel even weaker. She knew she still retained some of the spring in her legs, forged in the mountainous country of her childhood, where flat areas were rare, and every walk meant going up and down, over and over. The Pit had helped, the vast spiral and stairs building stamina, as had staying in the great towers of Eastsea before.

Flin’s thoughts drifted, seemingly trying to discourage her mind from the pain. Would the other woman really be able to tell her where her home was? Would she help, could she finally have an idea of where her sisters, her baby brother, and her parents lived? It had been so many years since she had left, so very long, and so far away. The thought that it was likely some of her family were no longer alive was always present, the idea that they might have died when she was searching for them filling her with a constant nagging guilt, as though it was somehow her fault she had been sold to Rharsle. Her baby brother could easily be a father by now, several times over. He would not know her, not at all.

The drifting of her mind definitely helped mask the pain in her legs, each thought smoothing her steps, burying them in larger issues which had, for so very long, played through her thoughts with little chance of a resolution. She knew she was fixating on the simple fact the woman currently tending her baby looked a lot like her, her accent tickling memory and reigniting hope—and she also knew this was foolish, at best, and potentially dangerous. Even assuming she could survive this, there was no guarantee the woman knew the way to her home. None at all. She tried to think of something else and instead found her thoughts flitting back to the stairs she had climbed and descended in her life: those beneath Youlbridge, those on the side of the mountain of Taura Furnace, or those near Annezi Gap, carved into the cliffs and haunted by Sprites. Stairs, and the climbing of them, never got easier, either physically or, apparently, mentally.

She began to consider the simple act of going from one step to another as a form of meditation, accompanied by a wearying, burning pain, perhaps some form of redemption, or cleansing, then the woman stopped so suddenly Flin almost collided with her rear. Her finger was on her lips.

‘There are just a few more turns of the spiral, then we come out,’ she whispered. ‘We emerge in a tangle of fallen trees, behind a large pile of loose rock, about three arrow flights from the top of the other stair. If the wind is on our side, we might be able to get close enough before the dogs scent us.’

Flin nearly swore; she had somehow forgotten about the dogs. She hoped they were simply tracking beasts, and not bred to attack. She hated hurting animals, it somehow seemed more cruel than hurting other humans.

Instead, she nodded, and whispered back,

‘Will you shoot him?’

‘Yes. I have no intention of a hand-to-hand scuffle on the top of a cliff and, I guess, you don’t either. Besides, I want to know all about you before making a decision on what to do with you, and that would be hard to do if you are mangled at the foot of the cliff.’

Flin nodded in response. She knew she still held some cards for that coming discussion, some things which she could bargain with, but she also knew this was the endgame, the show of hands coming at her fast.

‘Let’s go. Move carefully and slowly, don’t make any sudden movements,’ the woman said.

Flin drew her knife and followed, refraining from replying that she knew very well how to move quietly, to sneak and to stay safely hidden, thank you very much. Most of her life had been a never-ending combination of these things, after all.

This close to the top, the stairs were considerably more worn, channels and grooves showing where rain and storm had carved patterns into the treads, hollowing, redistributing, sculpting. Movement on the walls made her shrink back, the lantern light catching a moving tableau of fur and leathery wing, thousands and thousands of small bats staring back at them, unwilling to move into the brightness of the day, irritated to have been disturbed. She was glad they were both moving carefully, slowly.

After the bats came several large spiders, each in a web along the wall, each web holding several bats, one or two still flapping feebly, others shrouded within silken strands, waiting to be eaten, paralysed. Flin thought she knew exactly how they felt.

She realised the light was changing, the sun intruding into the shaft, day returning to her eyes. The woman shuttered the lantern and hung it from a wooden peg protruding from the wall. The daylight dimmed, but there was still enough for them to see the way ahead.

Here, the steps were covered in more detritus, twigs, leaves, and bigger branches and things moved in the loam, scuttling, scratching and scurrying away from the heavy tread of the women, making Flin long to be out in the open. Centipedes, beetles, other spiders and even a single, swift snake, all headed for darker corners and cracks, but Flin still trod very carefully, squinting down at where she placed each foot, eyes as wide as she could make them, pulling in as much light as possible.

Then they were out, the daylight blinding, even after its gradual appearance. Both the women stood still, waiting until they could see properly again, crouched among a den of trunks, branches and creepers. The pile of rocks seemed to be ancient detritus from long ago. Perhaps a building had once stood here, or perhaps it was simply rubble from the stairwell.

The woman pointed, and Flin followed. It did not take long to rejoin the trail, now covered in several bootprints, dog tracks and, here and there, the lighter imprint of her own, earlier passing. From the view, and the trees they passed, she realised the steps must not have been entirely vertical, as they were closer to the top of the stair than she had thought they should be. Another short distance later and they could see two dogs, curled on the trail with their backs to them, ears twitching, noses occasionally raised to the air. There was no sign of the man.

The woman paused, crouching, silent and shadowed, a part of the forest. Then she nocked an arrow, drew back the string, and released. At first, Flin thought she had meant to hit one of the dogs and had missed them, then she realised the woman had aimed beyond the pair, deliberately targeting the brush and trees. Both animals leapt up, yapping and barking, then howling, heads pointed further up-trail, tails wagging, moving back and fore with the ferocity of their warning.

Only one arrow left, but the ploy worked.

A man appeared from the stair, attention firmly fixed in the direction the dogs were indicating, a long knife naked in his hand. He was wearing leather clothing, buckskins worn with time and use. He was clearly a woodsrunner, knee-high boots, several pouches on his belt, and a small haversack over one shoulder.

The woman moved slowly to nock the final arrow, then she pulled back and released, with little time to aim, yet the shaft flew true and caught the man solidly in his back, burying itself deeply. He stood for a moment, raising his free hand to his chest then, slowly, he dropped the knife and sank to his knees.

They moved, the bow discarded, knives out ready. The dogs were concerned and began to bark and growl as they saw the approaching women but, despite the snarling, despite the raised hackles, Flin knew they were simply scared.

‘They won’t attack. I don’t think they’re bred for that,’ she took a closer look at the animals, both of which were thin, both of which carried scars, scars which looked man-made, ‘and I don’t think they were well treated.’

The man had not moved from his knees, his hands initially both raised, then slowly falling to his sides. The dogs did not attack, but held back, keeping their distance.

When they reached the man, it was clear he was already dying.

‘He’s drowning in his own blood, he doesn’t have long,’ the woman said. She stepped forward, knife ready to end his suffering, then paused, looking at Flin and back again to the man. ‘Tell me, why did you try and take this woman’s baby? Why did you follow her for so long?’

Flin took a step forward, but stopped at the outstretched arm and sudden words from the woman.

‘That’s close enough Flin, I want to hear his words, while he can still just about speak, come any closer and I won’t give you a chance to tell your own story. Understand? I am in your debt, and I do not want to hurt you, but I will if I am forced.’ She looked back at Flin and added again, ‘Do you understand?’

Flin stopped and nodded, her mind racing. She knew the woman was a better fighter than she was. If she ran she knew she would make it, there would be no reason for the woman to follow. But she would have to leave Kadan, have to leave her whole life, and she could not do that. She could fight, maybe there was a chance, but then she would have to take her child from the other woman, and run, hard, again. Running, running, always running. She was tired of running. No, she could not risk Kadan.

Flin sat down hard, and waited.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.