Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the eighth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

The Way of Song and Story

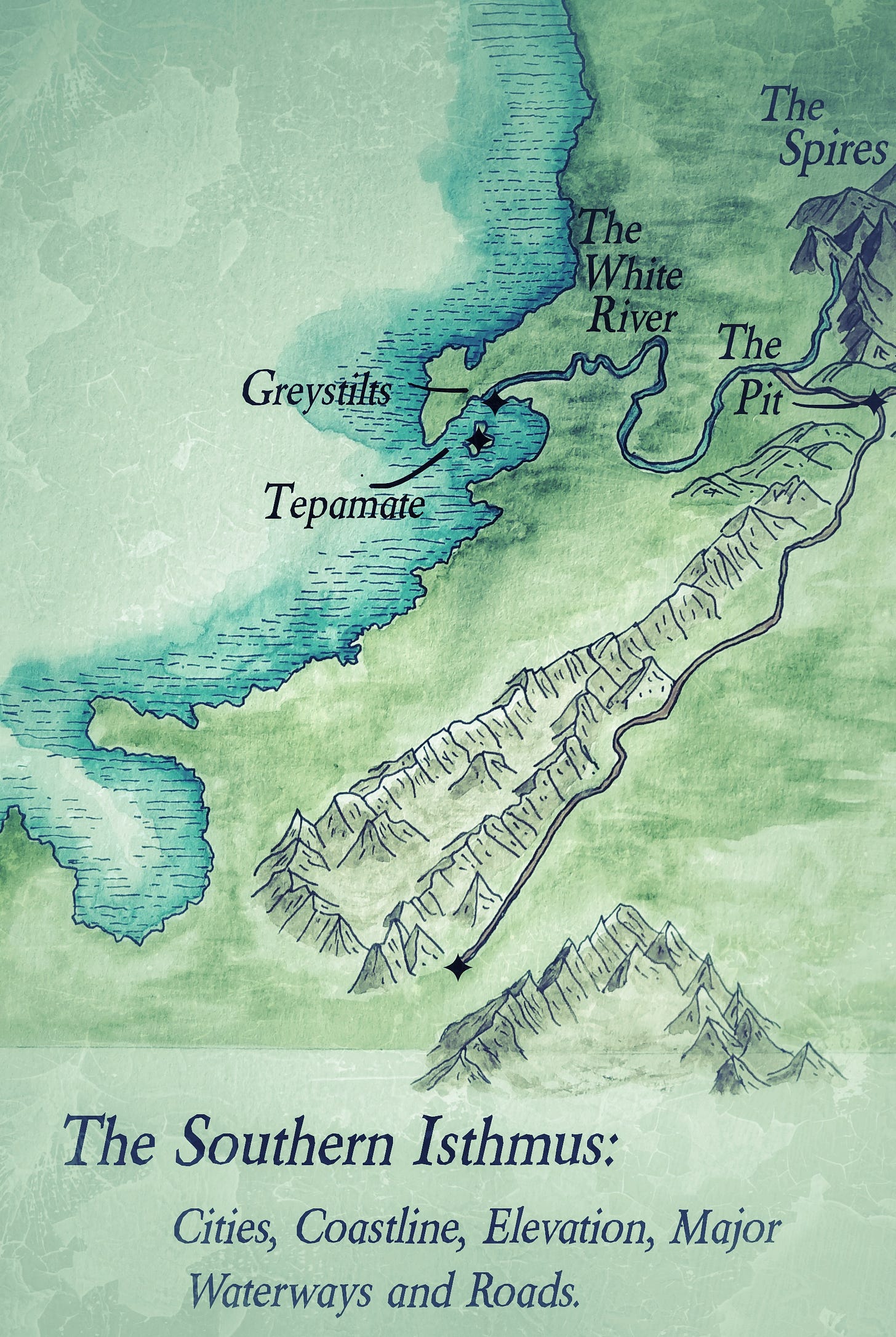

The present: somewhere north of The Pit

‘I think we will keep walking until the sun sets. We shouldn’t go on in the dark tonight, there’s too much traffic here,’ Flin gestured, pointing to the animal tracks with the spear, ‘and I don’t want to slip while running from a bull, I doubt you’d cushion my fall much, Fluff.’ She gently stroked the down on the baby’s head and kept walking.

Twice, she had heard large animals on the trail ahead and, twice, had made enough human noise to ensure they moved off into the forest. Sometimes, when she thought about it, she was sad that animals instinctively seemed to be aware of the danger presented by humans. She knew it was not the same with all the Talking Races, some of whom had very different relationships with animals, more peaceful partnerships. Perhaps there were places where humanity had not ventured, had not taught the animals to be afraid, but she knew she would not find her home by seeking them out. Boncliff had been on the edge of the wilderness, but the animals she encountered as a child had still tried their best to avoid the villagers.

Flin was relatively sure she had lost her pursuers. However, although she had walked a considerable distance since freeing the wolf, she was painfully aware that the trail she presently followed left little difficulty for the tracker; if the dogs recovered her scent, then they would close that distance fast. Once she had crossed the bridge into the graveyard, she had been limited in her choice of direction then, after she had exited and found the crater, she had only two real choices to follow. It would not take an expert tracker to find her, and she silently prayed for rain to wash away her scent and dusty prints. The sky, however, remained blue and clear and the sun hot.

She heard the waterfall before she saw it, not the roar of a fierce rain- or snow- laden torrent, but the gentle splashing song of a shallower channel. Flin entered a large open space, grasses replacing the thicker forest she had been walking through. Several small deer stood watching her from a safe distance and, overhead, she saw large birds catching the warm air rising from the cliff edge to her left.

The trail went straight to another large obelisk, tall and dark against the sky and, beyond, was another bridge.

‘Whoever these people were, they certainly liked their bridges.’ The baby twisted in the sling and looked up at her, as though puzzled by the sound of her voice, seeing her for the first time. He smiled, then kicked and pushed against her with his legs. ‘You want to stretch a bit? Me too. How about we find somewhere close to camp, maybe see what food I can collect?’

They walked to the bridge, Flin pausing to study the giant stone marker in the middle of the trail, tracing a hand over the sun-warmed stone, worn smooth by large animals scratching and rubbing against it. Nature always found a use. There were fewer markings on this stone than she had observed on the other and she guessed it was simply a way-marker, although why anyone would import a strange, non-local stone to create such a thing, she was unsure. In her experience, ancient cultures made as little sense as modern ones and, in her travels, whenever she queried such things, she was usually rewarded with a variant of the answer, ‘It’s just the way.’

Why did the people of Youlmouth cover their faces with masks? Why did those in Tah Djolah always eat with their left hands? What was the significance of the open-palm greeting in Beya? When did it become customary for those in Annezi Gap to depict a crescent moon above their doorways? All these questions were answered and translated the same, no matter the language: it was just the way.

Flin was delighted to see a large, lone fig tree, the only cover between the marker and the river crossing and, as she got closer, even more thrilled to see several ripe fruits on the ground beneath. Once she had picked the ants from them, she ate three, then placed others in broad leaves she collected from the riverbank, tucking the neat packages into her haversack.

The bridge was wide, sturdy and strong. On the upstream side it was well worn but still solid, the thick pillars smoothed by centuries of waterflow. It was low but wide, as though it had been made for carrying heavy waggons crossing the shallow, tumbling river. After she crossed, Flin followed another animal trail along the edge of the watercourse, towards the great crater. She wished she knew more about how rocks worked, as she could not understand why this river flowed down a series of steps, almost like the strange formations she had seen in certain caves. Looking down, she wondered if this was a good place to climb, but some of the rock looked exceedingly smooth, polished by the actions of water and pebbles carried in the flow. There were fish in the water, small and darting, then a larger, chasing the others. She knew how the minnows felt.

Flin was thirsty and tired and drank her fill, remembering Rharsle’s explanation that the best way to carry enough water was inside you, refilling her battered canteen once her thirst was slaked. She needed a new canteen. She needed many new things. Much of what she had left behind she could make herself, given time and the right materials, but she knew she had to be sure she was no longer pursued before she did so.

She knew she had been right about not returning to the south. The Pit would certainly replenish her depleted purse, not as quickly as if she had flute, drum, fiddle or kora, but singing, leading dances and storytelling was always enough to earn coin, if you were good enough. And Flin was definitely good enough.

But The Pit had almost killed her and those men, those angry men with their imagined debts and misguided sense of ownership, were unlikely to have quickly forgotten her. Even in a city of that size, the risk was definitely too great.

East to Gateway? Then north to Eastsea? This was perhaps a wiser option. The wild forest would thin out the further towards the dawn she walked, as long as she kept the jagged peaks of The Spires to her right. Rolling, forested hills eventually gave way to flat plains, with farms, towns and villages along the way. Vast plantations and farms, growing vines laden with grapes, oranges, lemons, berries and other fruit, rice, nuts, poppies, hemp, and cannabis covered much of the area to the south of Gateway, stretching along the Great South Road on the way to Tah Djolah.

Flin knew she would have to walk for anything up to thirty or forty days, pushing through wild and dangerous forest with no roads and few pathways, before she reached the first tiny human settlements to the east: trading posts for trappers and hunters, small resupply stations, mining towns, all fortified with stockades and militia to protect them from those who did not want them there, those who already called this forest home. Maybe only twenty days if she got very lucky. Just twenty days, maybe. It was tempting, but it was also the direction any pursuit would guess she was most likely to take.

Which left two, much tougher, options, assuming she disregarded building a home out in the middle of nowhere and raising her child alone in the wilderness.

She could walk west, all the way west, then turn south at the coast, avoiding the White River, Greystilts and its labyrinthine canals, and their direct trade connections with The Pit. Instead, she could hire a small boat from one of the fishing villages that lined Mangrove Bay to take her directly to Tepamate. A long and very difficult journey: the coast was wild and rugged, with inlets, bays, cliffs and broken ground for many days journey.

The last time she had seen the city of Tepamate, she had been returning from the thousand thousand islands of The Ribbon, islands that stretched as far north and as far south as could be travelled. The waters had been calm and clear that day, and the bright sun had illuminated the sunken city stretching in every direction around Tepamate. That very evening, as soon as she had secured a room, she had crafted a new song about the experience, singing it for a whole month before it was stolen and no longer hers alone. That was the way of song and story, they did not belong to the creator any more than they belonged to the listener. They were wild things, never tamed, like the ocean, rarely showing the same face twice.

Flin knew she could easily live out the rest of her days travelling The Ribbon and barely scratch the surface of what was available to see. The Countless Isles were a maze, every small settlement different to the last, fiercely independent, yet sharing a common bond through precisely this sense of freedom. She knew she could tell her stories and sing her songs, grow old and fat and raise the baby in relative safety, maybe even find a good man to share her intended bad old age.

But she would never find home there and, even after more than two decades, she had still not lost the hope of finding her family, her own people. As much as she loved the islands, they would never be home.

Finally, there was Westsea. She knew the whaling port well, having sailed from there after spending a winter in small and smoky, whale-oil-scented taverns. The whaling fleet would take a few passengers as they headed north every year, dropping them off at what was often their last watering and supply point: the town of Mamak, to the north of the Fjordlands and the Skerrysea. From Mamak it was easy to either head inland to Fea Little and the other free cities of the Interior, or back out west to the northern Ribbon, as she had, all those years ago.

‘Names! Cities! I have no idea which is best,’ Flin said, and the baby looked up in silent response. ‘All compasses point south. Everyone knows that. But I don’t know which way to go. A long time ago, before the Ribbon, before the Reversal, when the world was fresher and Gods walked amongst us, there was a time when the needle pointed the opposite way, then came…’ She cut herself off with a disgusted sound. The baby was not a suitable audience for such a tale.

She knew Westsea was the safest option as a place, she had contacts there and had left on good terms, but the way was not the easiest. Perhaps the most dangerous physical route of all her options, as rough as the coast south and much longer, it was also the least likely direction any sane person would travel. Weeks and weeks of wilderness travel with no other humans for countless days of travel or, at least, none that she wanted to meet. As with most wild places, there were tales of blood-drinkers, cannibals, skull-worshippers and worse. There were also the stories of other Talking Races, some friendly, others not so kind. The Twigs would avoid her, she knew that much, but the tall, silent, and rarely-seen Forest People were known to persuade travellers to not cross lands they considered under their protection. Sometimes, such persuasion proved fatal. Then there were others, the whispers of terrors even the cannibals avoided.

‘No. I, we, we’ll risk it. Everyone loves songs, right, little one? Even those who’d like to cook you must love to dance? We’ll follow this circle around, then strike out somewhere north-west as soon as we find a decent trail. Yes?’

The baby did not reply but Flin felt better.

It did not take long to find a decent place to make a camp: a tumble of fallen trees, vast trunks twisted together, forming a barrier to wind and any potential rain, not that the sky gave any hint of precipitation. Underneath, it was cool and mercifully free of snakes and insects. Flin cleared what leaves had filled the space, then blocked one of the two ways in with fallen branches, snapped off and pushed into the earth to form a barrier. Behind this she piled more branches, twigs and armfuls of moss, loam and leaves. Soon it was windproof, a snug nest for them both to spend the coming night.

She left the baby sleeping in the hollow and checked her handiwork. No one would see them, even if they were close, it looked just like a natural collection of debris, no axe scars or the bright flash of freshly cut or broken wood to give them away.

To the front of the shelter she built up two more piles, giving her a route in, but preventing anyone from seeing in. She had no intention of lighting a fire in the night, but she did gather and store firewood and tinder, in case a large predator found them. Everything was bone-dry and it would not take long for her to kindle a fire as a last resort.

Flin also collected some small branches and twigs to carve into traps. As she had gathered her shelter materials, she had seen signs of smaller game, trails too low to have been made by anything big. If she was lucky, she might have some meat in the morning. The temptation to head back to the river and build simple funnel fish traps from the rocks was strong, but she knew that once the sun set the night arrived swiftly: better to stay, carve the trap pieces, and feed the baby.

As she worked, she sang, a song of the early evening, when the light is drifting away from the day and all is calm. It was an old song, one she had known from her childhood, from before Rharsle claimed her. She had not shared it with the baby before, and he seemed to like the tune.

Flin fed the baby on a mixture of chewed-up fig, blended with powdered jerky and a little water. He was hungry, and enjoyed the sweet fruit flavour. She changed him once more, marvelling at how often he seemed to need his moss swapping, and made a mental note to collect more when she set the traps.

Once fed, she sang to the baby again, all the while cutting notches and sharpening points, making enough for four simple deadfall traps. She had learnt her traps and snares from her grandfather, and had been bringing rabbits, hares, mink, marten, and other creatures back to the farm long before that fateful night at The Dancing Shepherd.

The light of the day was fading as she left the sleeping baby, the birdsong was strong and a chorus of insects provided a counterpoint. Flin set the traps swiftly, action long-practised needing little thought, then she walked back, eyes peering into the gloom, gathering moss and more fallen fruit on her way.

At their small camp, it was even darker, the deadfall and brush cutting out the little light left. She could not see to pick insects out of the fruit she had collected and briefly considered lighting the fire, before she held back. It would not be wise, better to wait until the light of morning. She still had most of the figs she had collected earlier and ate them, licking the sweet juice from her fingers, before chewing on some strips of hard jerky and relishing the sensation of her first relatively full stomach in days. She twisted a hair around her finger, but resisted the urge to break it free.

As she closed her eyes, Flin listened to the sounds the infant made, small sucking noises and tiny sighs, and it terrified her. Such a small thing, so fragile, so breakable. He was such a good little bundle, barely protesting, barely screaming, rarely even crying. She finally fell into a broken sleep, and dreamt of more terror.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

Very nice! I am getting "into" it.

I've read only two excerpts but am really enjoying your writing. I am wondering if you have read Ursula K Le Guin's the Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. I feel like your work is in line with her ways of thinking about narrative. Thanks for sharing your work here.