Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the twentieth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

Twists and Turns and Fear

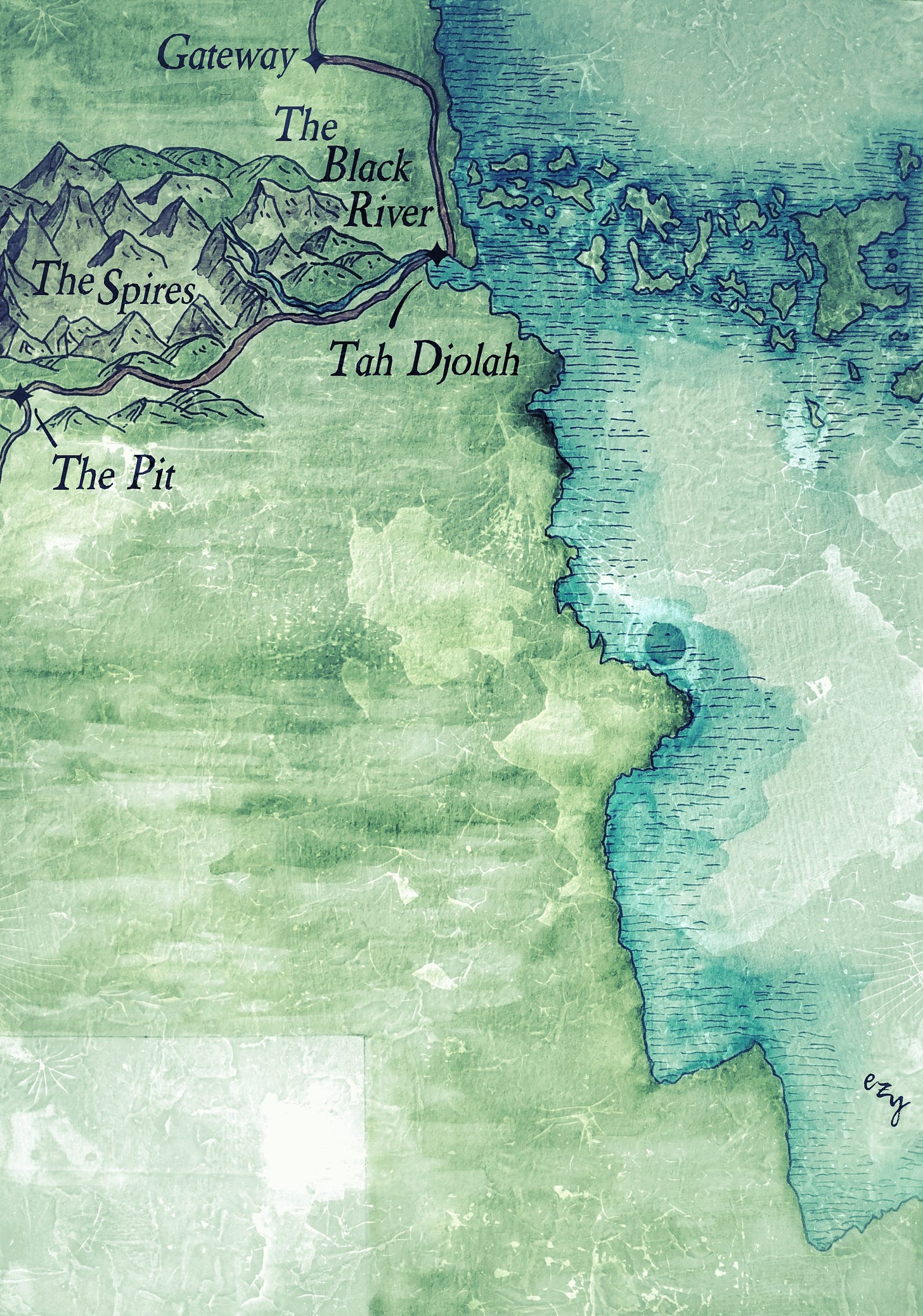

The Present: somewhere north of The Pit

The sun had risen higher, several handspans above the forest and the rim of the giant basin, and the day was already warm when they set off to track the man. Flin knew that this far south there were long summers and much warmer winters than those she remembered as a child. It had been years since she had experienced a cold, deep winter, with snows that covered all.

To the south the mountains shone, the angle of the sun catching high valleys, sharp ridges, darker hollows and deep ravines. Later in the day the sun would wash out these features, paint all in indistinguishable silvers and pastels. As she looked, Flin wondered if anyone had ever climbed to the tops of these peaks. The nearest did not appear to be the tallest, but she knew it was, and that it was sacred to the peoples of this corner of the Isthmus, human and otherwise. The peak was wreathed in mist at the top, its slopes creating a climate of its own; smoke-like and strange, the clouds parting to reveal flashes of bright cliff face and rich forest.

‘I never get bored of that,’ the other woman said, watching her, and surprising Flin, who thought she had been studying the ground for tracks.

‘Do you ever wish you could climb to such places, see what the eagles see?’

‘Yes, I do. And I do climb. No matter where I am, every couple of years I’ll make the effort, get to the top of a mountain. I did her,’ she waved at the mountain, ‘earlier this year. It was not easy, but it reminds me of how tiny I am and I like that feeling. Would you believe there are the remains of a building up there?’

‘Please tell me your name,’ Flin said, ignoring the question, ‘it feels odd, not knowing. How did you come to be out here?’

‘Later, Flin, remember? We’ll do all that later, once we’ve got this out the way.’ She gestured to the ground and tapped the quiver at her hip. It held the five arrows Flin had watched her select, each with a wickedly sharp flint point and striped fletchings.

‘Why stone points, why not steel?’

‘Stone is less likely to rust out here, easier to maintain and much easier to find and replace. We made these and, I think, it’s sharper too. And we didn’t have to carry any steel heads.’

Flin had heard other archers say the same thing and she nodded in reply, thinking back to the times she had carried a bow. Over the years, her skill had improved, simply due to the need to supply herself with fresh game. Sling and bow and trap, the three had kept her alive when all her supplies had gone and fruit, fungi, nuts, seeds and plants were out of season.

‘Are you sure we still have the trail?’she asked, as the woman returned her gaze to the ground, moving with purpose once more.

‘Yes. Look.’ She stopped again and pointed to a moss-covered log but, despite all the time Flin had spent increasing her knowledge of tracking, she could see nothing. ‘There.’ The woman pointed closer, catching Flin’s baffled look.

There was a tiny fracture in the moss cover, as though it had been parted and put back together again, almost perfectly.

‘And there.’ She pointed again to where a leaf had been pushed onto the forest floor, impaled on a sharp thorn below.

Flin nodded; the woman’s skill far outweighed her own and, for that matter, the man who had taught her. She forced herself to stop looking too far forward, to stop considering what or whether the woman could or would teach her. There was no guarantee she would even let her live. Instead, she concentrated on the matter at hand.

The man had continued in his direct charge to the city’s centre. At first, he had barely deviated from a straight line, crashing through undergrowth, scrabbling over fallen trees and leaving an easy trail to follow. Then he had slowed, picking his route carefully, hiding his passage as much as he could with an arrow in him. Flin guessed he had initially fled, trying to put as much distance between himself and the woman who had shot him and killed all his friends, as swiftly as possible.

She was tired, but fuelled by adrenaline, by hope and by sheer will. She tried to remember when she had last been blessed with a good night’s sleep, when she had last felt truly rested, but she failed. Holding her hand in front of her face, she marvelled at its steadiness. If she still had her kora, she could play it perfectly, no matter the stress, the strain, no matter what horrors she witnessed. She knew she was born to play, molded to entertain, and the fact she had spent the last moons fleeing one disaster after another made her sad. It was such a waste of time, a waste of music, of song, of dance and story and love. She ground her teeth. She’d had enough of running.

They had started tracking the man at the glade where he had been shot. The ground was scuffed and patched with darker soil where he and his companions had bled, and where his companions had died. Their killer had dragged the stripped bodies off into the undergrowth, but Flin had still looked. A part of her wished she had not, their wounds and expressions would remain behind her closed eyes for a long time. She felt she owed it to herself to witness their deaths, recognising one of them as the man who had sold her dried rice and beans, another as the farrier who had grudgingly replaced the worn shoes on her horse: the horse she had been forced to abandon, along with almost everything else she owned.

She felt no pity for the men, no sadness at their passing. They had wanted to take her child and wanted her dead, and she wanted neither of those things. She did still feel a sense of loss over her horse, fiddle, gear, and supplies, however. She had loved that horse and fiddle.

‘At this rate, we’ll reach the centre soon, before the sun is highest.’ Flin was interrupted from her memories as the woman spoke, ‘I hope he moves away from the line he is following though. Honestly? I really, really don’t want to get too close to the middle.’

Flin was silent for a moment, wondering how to phrase her question without making it seem as though she thought the woman was more than a little crazy. She began to twist a hair loose from her head, then paused, drew a breath and opened her mouth, but was cut off before she could reply.

‘You’ll see. I can’t really describe it. It spins in your head, it shows you things that aren’t there, twists the way you think about life. Look, some years ago I broke my leg, thought I might die, then I thought I’d never walk again. This is worse than that feeling. Much worse. It gets in your head, spins…’ she trailed off.

‘I think I understand.’

‘How can you? It’s horrific, it’s…’

Flin took a step back at the woman’s sudden anger.

‘Have you seen the Maelstrom?’ she interrupted, ‘Have you been close to the centre line of the Ribbon?’ The memory swiftly kindled a surprising rage of her own, then she paused, breathing deeply, allowing the woman time to answer. When nothing was forthcoming, she continued.

‘No? I have. I went with a friend, a long time ago. What you are describing sounds very similar, it’s colours in your mind, something at the corner of your eyes, memories that might not be yours, twists and turns and fear, constant fucking fear. My friend lost himself there, went too close. So yes, yes I think I understand.’ Flin did not mention how the experience had affected her, or how she had been so lucky. She reached a hand toward the pouch at her throat, then stopped herself.

The woman was silent, mouth still open. Then she nodded.

‘Good. So let’s hope we don’t have to get too close to the centre then.’

‘Let’s hope.’

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.