Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the seventeenth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

Paid With Blood

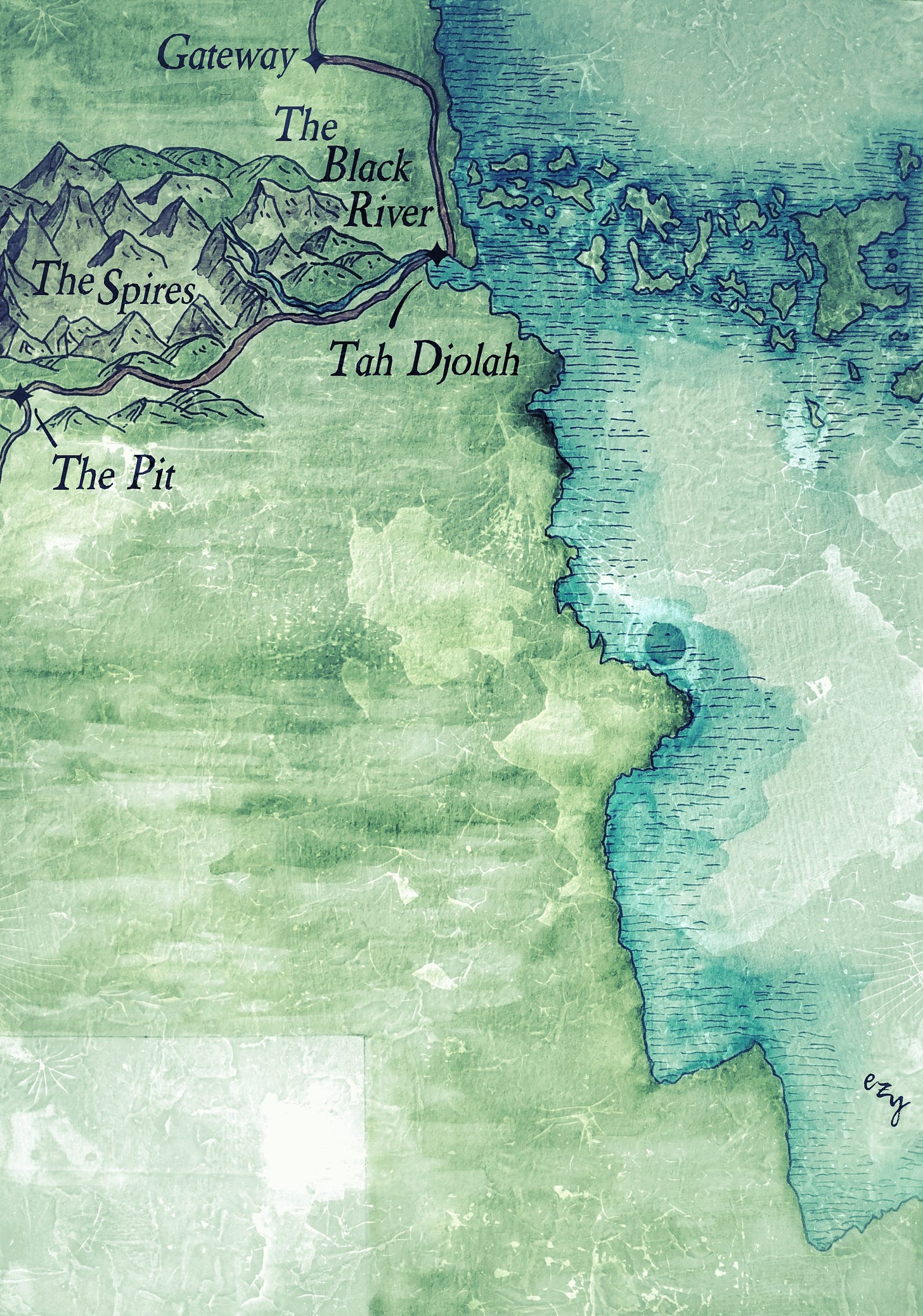

The Present: somewhere north of The Pit

For the first time in weeks, Flin allowed herself to take a moment of pleasure at the warmth of the sun on her face, at the scent of the forest, and at the sheer joy that she was still alive and, for a time at least, felt protected.

The woman led them along old streets and roads, some of which had a wide path worn into the vegetation, animal trails repurposing, routes reclaimed by their passage. Others had been recently cut away and cleared, bushes cut down and stacked here and there.

‘We cut down some areas, to give a better idea of the layout of the city. Now, here we are. We can stop here.’ She waved at a building which remarkably still possessed a roof.

There was no door and Flin waited to move inside. She was enjoying the sun.

‘We use this, and a couple of other places, to store things we find. You are welcome to take a look if you wish? One day, maybe, we’ll be able to sell some of it.’

Flin’s natural curiosity was piqued and she poked her head through the entrance, noting how thick the walls were, how tightly the stonework sat. This city had been built to last, yet it was entirely lost from memory. The thought was melancholy and an idea for a song appeared in her head. She hummed a couple of potential bars which seemed to fit, as her eyes became accustomed to the gloom.

Once she could see better, she noticed rough shelving lining the walls, little more than logs notched and fit together, each holding a substantial number of objects. A stairway in the corner led up, and every step was similarly covered.

The woman walked to the opposite wall, untied, lifted, and pushed back a panel of thin sticks, revealing a large gap in the stonework, which allowed the daylight more space to penetrate.

Flin propped her spear against the nearest shelf and stared. The items were astounding.

‘Can I touch them?’

‘Of course, just try not to break anything. Although these have lasted fuck knows how long in the ground, or in ruined buildings, so they’re mostly quite tough.’

Flin nodded in reply, distracted by all she was seeing. She picked up the nearest object, a small carving of some sort of mouse, life-sized and made from white marble. Each detail was incredible, from tiny ears and eyes to individual hairs scratched in the surface of the stone.

‘That brown? That’s not dirt, that’s the remnants of paint. All the carvings of animals we’ve found were once painted and, we think, all in exactly the right shade.’

Flin looked at her and back to the mouse, lightly rubbing her thumb over the carving. It was exquisite.

‘It’s beautiful.’ She carefully replaced it and trailed her hand over the rough wood of the shelf, looking at each piece displayed.

There were other carvings of stone, more small animals in white marble, bowls, candlesticks, and items whose original use Flin could only guess at, smooth stone and rough, red-veined or green, flecked or solid colour, no two pieces alike.

She moved to the next set of shelves. Here were pieces of broken glass in an array of sizes, panels mostly whole, some etched with geometric designs, others fragments, all in more colours than Flin knew was possible.

‘These are incredible,’ she said, then her gaze fell on the shelf below and she drew in a sharp breath.

This shelf held more glass, but these were vases and vessels, bowls and jars, all whole and intact.

‘We think they had been stored in crates, maybe ready for shipment when, well, whatever happened to this place,’ she waved her arm around, ‘happened. We found them all together in a cellar, partially buried beneath dirt, some cracked or chipped but the majority whole.’

‘Each of these is worth an absolute fortune! I’ve never seen work like this, I’ve never even seen some of these colours in glass, the craftsmanship is astounding.’

The woman smiled but did not reply.

The other shelves contained a variety of objects, some of which she had no idea what they were, some she could identify, and others she could guess at a use, then her gaze fell on the last shelf and the items it held.

She knelt down, one hand on the baby’s head, the other hovering over an array of carved pieces of bone and shaped ivory.

‘I guess you have a better idea of what these are than we do?’ The woman asked, crouching down beside Flin. ‘We thought that they may be…’

‘Pieces of instruments. Components, fret boards, inlays, tuning pegs, nuts, saddles.’ Flin picked up a peg and studied it, ‘These are very finely made, very fine; they look as fresh as when they were first carved, they’re, well, they are remarkable.’ Her fingers twitched slightly and a shiver ran through her arm and she carefully, and very deliberately replaced the piece where she had found it. The temptation to sweep everything into her bag and run was strong; with these pieces, she could make a beautiful new flute, a fiddle, a kora, and still have components left for spares, or even other instruments.

‘Like the glass, we found them together. I suspect they were also packaged for transport and trade.’

Flin nodded in reply, stood and slowly moved to the items on the stairs, unable to stop herself glancing back at the ivory and bone—it was almost too tempting.

Each step held several animal carvings, similar to those on the shelves, white marble, traces of paint and exquisite detail. There were creatures she recognised, whether lizards, small mammals, or birds, then there were others she had never seen before: a bird with a strange, upturned bill, a winged lizard, a frog larger than any she had ever witnessed, bigger than her head.

‘Now look in that.’

Flin reached out to the rough box the woman pointed to. Inside were tiny objects, individually wrapped in dried moss. She picked one out of the soft fibres and unwrapped it, holding it up to the light. It was also made of white marble, and was also a carving of a creature, only this was a small beetle of some sort, still bearing a trace of green paint; she chose another and found a bee, a third was a centipede, each leg sharp and perfect.

‘They’re all perfect. And they’re all the right proportion and the right size, aren’t they?’ she asked, as she carefully replaced the carvings.

‘Yes. For some reason every single statue or carving we’ve found in the city is the exact size and shape of the real creatures. Every one of them. We think they were all painted accurately too. Come, look at this,’ she said and beckoned.

Flin followed her to the opening in the wall, a part of her mind still thinking about the carved ivory, another, larger portion, wondering what was happening to the men who were chasing her, and what was happening to the naked woman.

She stepped out into a wide courtyard. A large tree grew out of the roofless building opposite, shading the far corner, the air filled with the calls of small chirruping birds flitting between branches. The space had been cleared of undergrowth and debris and was now mostly filled with a selection of simple, lean-to shelters, extending out from surviving stone walls. The other buildings that had once surrounded the courtyard were mostly ruined, gaping holes and piles of rubble all that remained of their grandeur.

In the very centre of the area stood a statue. It was humanoid, clearly of the Talking Races, but nothing Flin had ever heard of. It was a giant. She walked over and stood beside it, looking up. Her head barely reached the waist of this figure, its legs were the size of her torso and its arms considerably larger than her legs.

‘You think this is accurate too?’ Flin asked.

‘At first we thought it was just an outsized human, then we cleared the creepers and noticed the differences. Look at the face and hands.’

Flin looked; the hands were huge, the fingers different, bones longer, knuckles wider, but what was most surprising was that when compared to the others, the forefinger on each hand was tiny, half the size of the finger next to it. The span of each was vast, something the artist had captured perfectly. Like the other statues, this one was also white marble.

The head was in some ways similar to that of a human, but with a pronounced brow ridge, sharp cheek bones, small ears, thick neck and an underslung jaw. Long hair was tied back to keep it from the face, and fine, incredible craftsmanship gave the impression some strands had escaped. The feature which set it apart was the nose, which was flat against the face, barely extending beyond the cheeks, spreading wide and flared around the large nostrils, as though the stone was forever trapped inhaling.

The statue was naked and clearly a grown woman, despite her thick brow.

‘There are animal statues larger than this, including several I have no idea what they are, but this is the biggest of the Talking Races. I wondered if it was an Abriki, but from what I’ve heard, their hands and noses are more like ours.’

‘They are. It’s not an Abriki. Do you mean to take these statues out, get them up the cliffs? How?’ Flin asked, hand resting on the stone thigh. She could not begin to fathom the engineering needed to move a statue of this size, let alone hoist it up the cliff.

‘We shall see. We have not decided anything definite yet.’

Flin looked back from the statue to the woman, realising that for a brief time she had forgotten her fear, put the fact she was being hunted to oneside. She knew nothing of this woman, yet here they were, discussing ancient carvings. Something tickled her mind and she paused in the reply she been about to voice, mouth open, frowning, and changed what she had been going to say.

‘The City in the Circle.’

‘What? Go on.’ The woman waited, knowing there was more.

Flin ran her finger up and down the scar on her forearm as she thought, the movement briefly waking the baby, who made a contented gurgle before going back to sleep.

‘It’s an old, old song, the remains of a lay from goodness knows when. Rharsle, my teacher, said it was about the fall of a beautiful city, all marble and sculpture, song and laughter, trading in wine, in knowledge, and in art, protected from a central tower by a powerful magician. It goes on to mention words similar to fall several times in the eight stanzas he knew, something I had assumed was not literal but now,’ she waved her hand around her, ‘now I am not so sure.’

‘Can you sing it, tell me more?’ A frustrated expression crossed her face, emotions clearly playing against each other, and she held up a hand, ‘No, wait. Let’s wait until later and we’ve decided what to do with you. If we can tie this place to a name though…’

‘Then you will make more money when you sell things.’

The woman nodded and Flin knew she had another bargaining chip, another chance at safety.

‘Yes. We would.’

‘But you’d lose it all, all this.’ Again, Flin gestured, ‘It would be impossible to take these to a city, whether Eastsea, The Pit, or Tepamate, without drawing the wrong sort of attention. Others would learn your secret, follow you—or worse, find the city and kill you, then strip it bare. You’d lose it all in a year or two.’

‘Yes. We would.’ She repeated, then added, ‘Or we might, we can both be rather persuasive, when needed. But, if we found the right items it would not matter, we would be rich beyond our wildest dreams.’

‘Maybe. And what are your wildest dreams? Buy a farm, a tavern? A villa on the South Road? Maybe a Spirefloor in Eastsea? Or a palace estate outside Fea Little? And then what?’

‘You are very well versed in geography.’

‘I have travelled a long way to try and find home. A long, long way, over a long, long time. I know many stories and many songs, but you did not answer my question. What would you do with that wealth? How much would it take to feel safe from the wrong sort of questions?’

‘Well versed in geography and astute with it. I would rather have the option to do what I want with the money, than not have that option at all. I’ve spent enough years scrabbling around in ruins, in the dark, down at the bottom of a hole or in freezing mud, before I found the clues that led us here. Do you know what it is like to be poor, to have to build yourself up from nothing? To have debts, terrible debts that can only be paid with blood?’

Flin did not answer and they stood together in silence, each woman looking at the other, then back to the giant figure. A pair of yellow butterflies danced across the courtyard, flightpaths intersecting as they wove a repeating pattern, before landing on an outstretched marble finger.

‘What are you going to do with me? Us?’ Flin asked, twirling a stray hair around her finger, then tugging it loose, spinning it between thumb and forefinger, ‘I know you said to wait until later but, the thing is, I feel safer here now, with you, than I have in a very long time.’

The baby stretched out his arms and woke as the woman looked at Flin, a strange expression on her face, then cleared her throat and replied.

‘You should feed your baby.’ She turned away.

Flin looked at her back for a moment, before returning her gaze to the statue. The butterflies had disappeared. She stared into the eyes, wondering what they would have been like when the statue was painted. What colour were the irises? In what direction was she looking? Had the sculptor carved her from life, or memory? Had they even been friends?

She sighed and sat down, back to the giant’s calf. She had heard tales of huge people, who lived in the lands to the far north, hunting similarly giant creatures who made their home on the plains and deep forests beyond the Interior. She had always assumed they were just tales, as she had assumed the Bearmen were not real. When she had seen her first Abriki, she had been shocked that the stories were true. When she had stood at the bow of a Seafolk vessel and watched the vast towers of Eastsea approach, she had been surprised that their height and magnificent size were every bit as immense as the songs said. When she had sailed into Tepamate, watching the sunken city gleam beneath the waves, when she had travelled the Ribbon, witnessed true magic and barely survived the experience, she had still doubted other tales, still wondered which were fiction. Maybe all stories were real, truth easier to digest when it was carefully wrapped in fable.

Flin raised the baby and sniffed. Time to change him again. Her movements were automatic, mind lost in thought.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

I love this story so much. I'm going to be very sad when it's finished. Flin is such a cool character!