Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the thirteenth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

No Hero

The past: below Youlbridge

There was something there, in the dark, and Flin paused, ears straining to catch the sound again. She was sure it was not her imagination, not this time.

She and Kadan had wandered through the Maze, carefully, slowly, checking for traps, for any sign there was a way out.

After the impossibly heavy iron grille had fallen, she had wasted time trying to move it, first by lifting, then by searching for a hidden lever or mechanism. It was too heavy to lift and she had found no way of opening it, and she cursed herself for trying. She had been forced to run, deeply conscious she could set off another trap, when she had heard rapidly approaching voices.

Unless they found a way out before the lantern oil burnt away, they’d be forced to stumble blindly through the dark, hoping against hope to find an exit, they succumbed to another trap, or until their supplies ran out and they starved to death.

These lower tunnels and chambers held water aplenty, which was a mixed blessing. Flin had no way to boil it and make sure it was safe to drink, and her boots and leggings were soaked through. Several places had been flooded to knee height and the going had been slow, one foot constantly reaching forward to check for any sudden drop. Step, check, step, check. She hummed a simple tune as she moved, trying to keep herself calm, one two, one, two.

Flin walked further down a long, sloping tunnel, then along a level, wide corridor, its walls constructed from perfectly faced rock, each stone the exact same dimensions. At the end the corridor stopped abruptly, a spiral stair offering two simple choices, up, or down even further.

‘Let’s go up. I think we have gone down too far already,’ Flin whispered, and set off taking the steps, one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four. Her legs were tired and aching long before she came to their end: a short corridor, ending in a thick wooden door. She checked it carefully, but could see no obvious trap. It was unlocked and unbarred, and led out into a larger tunnel.

She paused and fed Kadan again, before they set off once more, still silently counting the tempo.

After a short distance, a shaft of light came into view and Flin approached carefully, slow and deliberate, pausing to listen closely. She was sure she had heard something, something in front of her, hidden in the dark, beyond the light.

There, again! A slithering sound, like a gloved hand being stroked across sanded wood. She was sure it came from something large.

‘I can hear you,’ she called ahead, softly, pulling back the bowstring slightly, arrow ready to loose into the darkness, but she heard nothing more, no reply.

Another wave of terror threatened to overwhelm but, somehow, she managed to regain control. She could not go back, she would go forward, sound or no sound.

‘No,’ she spoke firmly and loudly, ‘I will not let this beat me. No, no, no.’

Flin took a step towards the light, then another and another, slowly releasing the tension on the bowstring, her muscles still ready to pull back and release, her body angled just so.

The tunnel widened; she was sure this was a former gallery, one of those places in the Maze where spectators could catch a glimpse of the Maze Fighters, see who was still alive, who was injured, perhaps even witness a fight. Flin knew that sometimes doors were kept barred, movement carefully controlled by those who ran the event, only opening them to force a fight or encounter, whether the fighters themselves, or between participants and something bred with the sole purpose of killing them. The opening would once have been much wider, tiered seating spreading back from the edge.

She hoped the door ahead was open.

‘I guess it is,’ she whispered to Kadan, to the thing in the darkness ahead, ‘Otherwise, you would have starved to death a long time ago.’

Unless whatever she had heard could fit through a gap she could not. The thought was not reassuring.

Risking a glance up into the light, she saw clear, star-laden skies suddenly obscured by dark clouds, the specks of light reappearing, then vanishing once more. It took her a moment to realise the clouds were smoke—thick, black smoke. The city was burning.

‘Fuck.’

The wind must have swirled, changing direction overhead, as she heard the roaring of flames, accompanied by screams and calls, and violent, cracking sounds, then all was silent once more.

Only, she realised, it was not entirely silent. The slithering sound was there again, a whispering on stone, coming closer.

Flin knew the tales of the creatures imported, bred, starved, beaten, tortured and twisted, meaner and meaner, before being used in the Games. She had learnt and sung the songs, recited the stories of the greatest of the Maze Fighters, of the beasts they had to overcome. Wherever she travelled, she picked up new material, a new repertoire; audiences always loved tales of local heroism and events.

She whimpered. She was no hero.

‘Every Mother is a hero,’ she spoke the words aloud, the saying coming back to her from when she was very young.

The sound came closer, faint clicking now mixed in with the slithering noise, claws on stone. Flin drew back the string once more, bringing the fletchings to her cheek, resolve firmed, hand steady. Nothing would take Kadan. She may be no hero, but she would fight. No one and nothing would take her baby: she was a Mother.

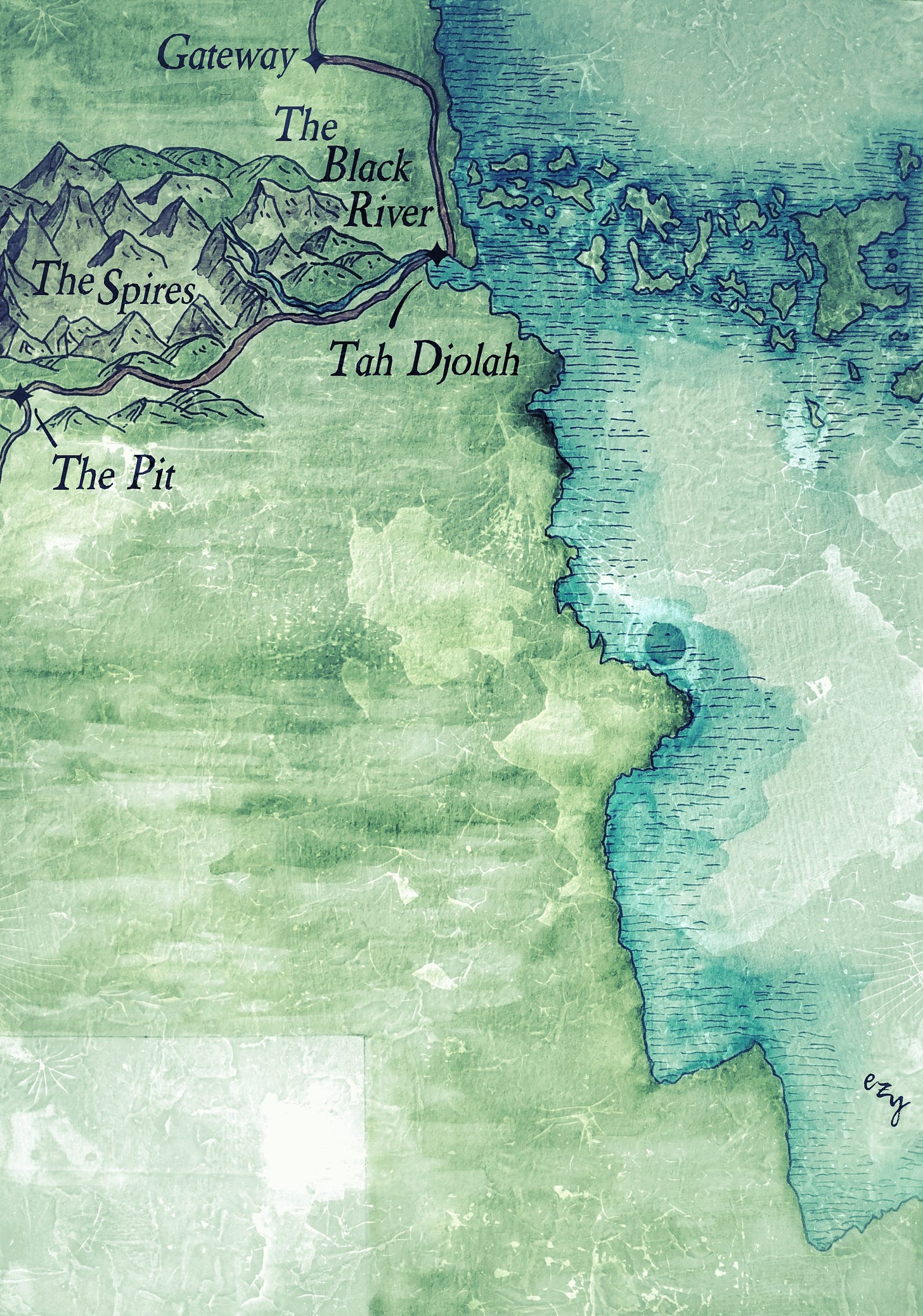

The present: somewhere north of The Pit

Flin quickly realised the trail she followed had once been a wide road. Hard paving stones and cobbles were buried beneath thick loam and the detritus of time, occasionally reappearing where roots had buckled the surface, forcing stones back into the light.

There had been no further traps, but she had not let her guard down, that was a beginner’s error and, despite what the stories said, in these situations, beginners usually ended up dead.

Even as she thought this, considering all those tales where farmers’ children discovered they were secretly of elevated descent and were subsequently suddenly wise and capable beyond their years, a distant scream from somewhere behind her sent birds screeching into the air, a huge flock wheeling overhead, wings black against the blue skies. Flin was sure it had been the trap she had avoided, and her pursuit had not: farmers’ children, beginners’ error. Assuming all six of those she had seen on the stair had made it to the bottom without injury, that left just five, minus the man still screaming.

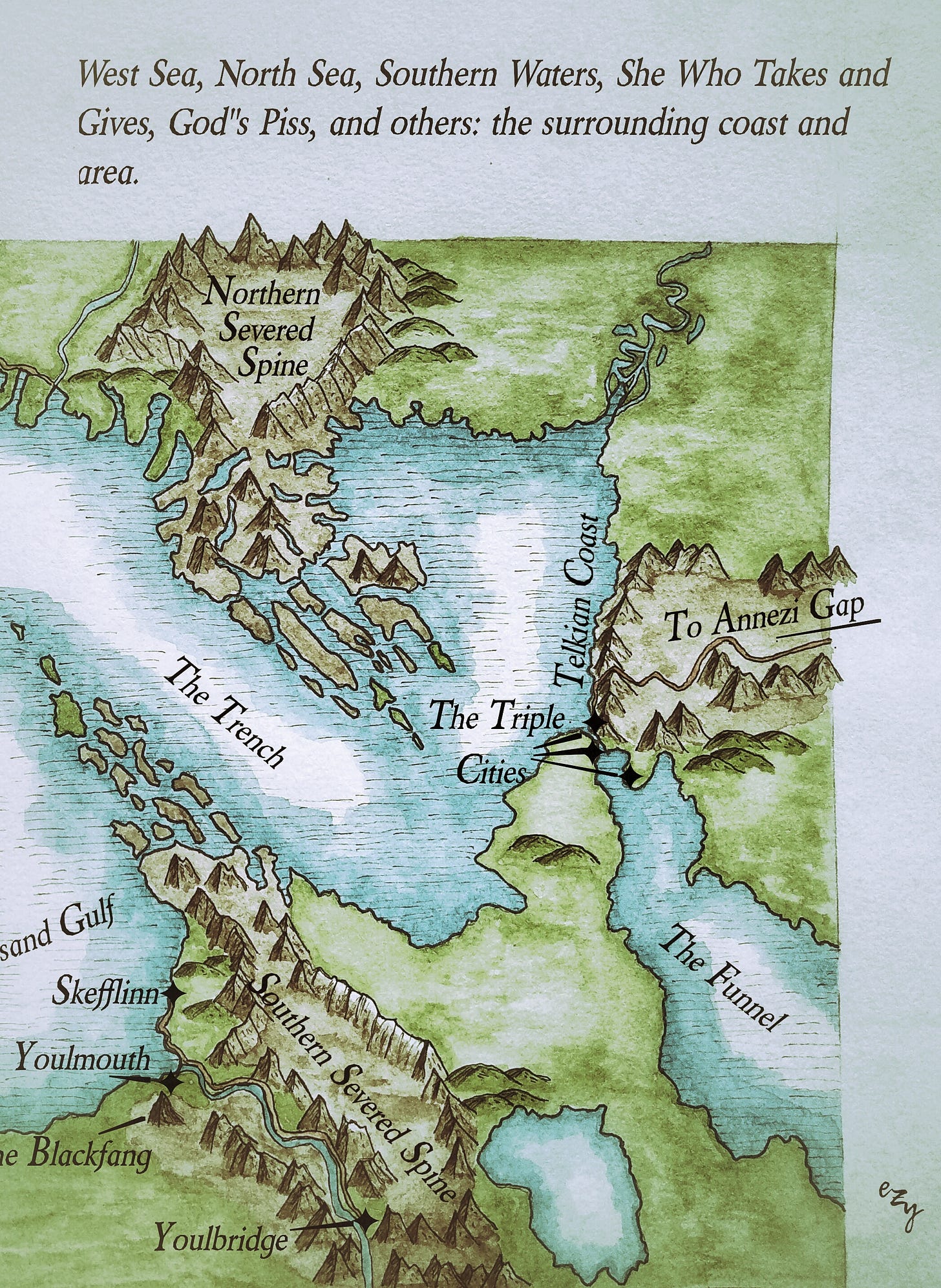

Just five men, and she was certain they were all men. Their village had been unlike anywhere Flin had ever visited or heard of, run by a solely male group, the women docile, curiously silent, with timid eyes which rarely left the floor. Before her hasty retreat, she had seen more than one bruise on the few women she had encountered. In all the other places she had ever visited the village council was always mixed, sometimes led by a man, sometimes by a woman, often with no leader at all, just a majority vote. It was the same whether it was the Motherhood of Trade in Eastsea, the Seven Fingers in Annezi Gap, The Pyramid in Youlmouth, or the smallest mountain village in the Severed Spine mountains. People worked best together; all of them, regardless of gender.

Five men standing between her and freedom, six if she included whoever was still screaming, seven if she added the man she assumed remained with the dogs. The screaming stopped abruptly.

Maybe not seven.

Ahead, the trail began to show more stones poking through, as though the old road was reasserting its dominance the further into the forested ruins she travelled. Flin continued, and a short time later heard the sound of running water. At some point in the past, a stone bridge had crossed a shallow river, but the five elegant arches no longer stretched across the water, whose course had shifted, cutting into the bank and across the trail.

The water was not deep and flowed clear, some kind of fish visible beside the opposite bank, tails flicking now and again to maintain their position, heads facing upstream. Flin’s stomach growled loudly, but she knew she did not have time to try and catch any food, not yet.

‘Mummy can easily find this again, when the men are gone,’ she whispered to the baby.

She was sure he had grown heavier on the flight from the village: her shoulders’ ached, despite being used to carrying weight. Perhaps it was simply that she carried the infant differently, holding him closer, protected. Perhaps she was too tired, in need of sustenance and rest. She thought of the last time she had led a pack animal, many years earlier, trying to remember what it felt like to walk long distances unhindered, the open road ahead, instruments cased, food in her bags and coin in her purse. It felt a lifetime ago.

After pulling off her boots, Flin waded across the water, using the spear to help her balance. The river came no higher than her knees at its deepest point but, looking at the undercut banks, she suspected that the tranquil flow would become a raging torrent after heavy rain.

Despite the rising air temperature, the water was still cool and refreshing for her hot feet. Long years of walking, sometimes with boots, sometimes sandals, sometimes barefoot, had left the skin hard and calloused, tough and relatively impervious to all but the sharpest thorn or stone. She could not remember when she had last experienced a blister.

The bridge was wide enough for wheeled traffic and strong enough to support elephants laden with freight, utilitarian beyond a pair of humanoid statues at either end, faces long worn by rain and now unidentifiable. Flin had seen ancient cities and encountered enough ruins to know that some stones wore away faster than others; the statues seemed to have been carved from the local limestone, the blocks of masonry for the bridge from something harder, imported. Once, this city had been rich. Now, it was forgotten.

She walked out of the river and followed the trail, which once again rejoined the old road. Clearly, animals had long ago learnt that this was a good path to travel; tracks of various ungulates were visible in the damp, churned mud: different sized deer, wild pigs, and something larger, perhaps buffalo. Here and there, she could see where they had paused to drink, not crossing the river, simply turning back around, to return from where they had come.

Ahead, the road forked in two, each route now flanked by low stone walls, with taller, still-standing fragments of masonry visible everywhere. Off to her right, Flin could see what initially looked like a stone outcrop, but was perhaps a building, to her left a suspiciously straight line of trees with a distinct gap between them—another road or street.

The ground rose to her right, whereas the left-hand route seemed to continue at the same level. Barely pausing, she chose right, the advantage of being able to look down on anyone approaching too good to miss but, before she continued, she ran down the road to the left, leaving deep prints, before carefully cutting back across to the other trail, treading only on rocks and masonry. As with all her recent attempts, it was a crude misdirection and would only fool them so long, but she knew every little helped her cause.

Five or six men.

‘Mummy can do this. I can do this,’ she whispered, ‘I will do this.’

As she moved, still trying to limit any possible trace of her passing, the question of who had set the trap at the entrance to this ancient city kept turning around in her head. Perhaps a trapper or hunter, looking for pelts or food, or a treasure seeker, raiding the ruins for gold, jewels or other riches. It was likely it was someone who really did not want company, ranging far into these wilder places.

Whoever had set it, Flin was aware, and awareness was a start. Better to be as wary as she possibly could be.

The trees to either side were old, gnarled and thick. The stonework she could see was worn by centuries of weathering. Whatever had happened to this city had happened a very long time ago. She stopped, looking down at a patch of damp mud; the footprint in front of her was not old, not old at all.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

Oh no! I'm so nervous!