Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the fifth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

The Maze Fighter

The past: to Youlbridge

After Rharsle’s death, Flin had travelled on alone, searching for something she remembered, always hoping to find her way home and always failing.

She knew that the winters were harsh where she had grown up, harsh and dark. In summer, the night sky barely dimmed, the sun merely dipping below the horizon, with only the very brightest scarce stars gracing the heavens. In winter, it was the opposite, with short, dim days and long dark nights, lit with countless pinpricks, constellations wheeling, the mournful howl of the wolves a constant song.

On certain nights, the sky would blaze with coloured lights, the Butterfly Dancers, her people called them, twisting, merging, bursting with colour and spectacle. She had never tired of them as a child, nor had any of the adults she knew. No matter how cold the winter they would all gather outside, silent, hands held and eyes teared, and not just with the chill.

She knew all this, yet still could not find her home. She knew the scent of the mountain air flowing down into the valley where her village hid, but could not follow her nose to her family.

Over the years, she had spoken to those taken in fighting and raids, or simply sold by their families into slavery. They would sit in kitchens and whisper of their homeland, yet few knew where to find it. Slaves were usually transported by ship, their route shielded from view, the stars shrouded by deck upon deck.

As was the local custom, Rharsle’s body had been washed, prepared, and embalmed, before being taken into the Countless Chambers, a vast underground labyrinth where, according to the priests, many hundreds of thousands of the dead lay in chamber after chamber, awaiting rebirth. At the time, Flin had thought the idea odd, but she had since encountered stranger rituals and had quickly learnt never to openly question ceremony or belief. At best, it was a swift ticket to receiving nowhere to sleep, nowhere to sing, but it could also risk a beating and thrown stones, or worse.

With no other viable option, Flin had taken the supplies Rharsle had bought and convinced herself she would find her way home, alone.

The cabin they had been due to share had been paid for and she had it all to herself, at least until the second night, when she attracted the attention of the ship’s navigator, a handsome man who spoke of distant shores and whispered of the scent of deep jungles drifting across calm, warm waters, lit green by strange underwater lights. He had thought himself a master storyteller as, she had later learnt, many sailors did, but she had disabused him of that notion, singing softly of the Tale of the Trees and, much later, telling him her own story, only gently embellished.

They had talked and laughed, and enjoyed each other’s company in silence too. She had been honest, as there seemed little point in being otherwise, telling him how she could not be the wife of a Starchaser and he had smiled, agreeing that it would not suit her. No one aboard seemed either surprised or upset by their intense, two-week relationship.

At the floating city of Nineteenth Harbour she had transferred to a swifter Seafolk vessel, spending a week sailing twice the distance in half the time.

Two months later, she had realised she was pregnant.

By then, she had travelled far inland, beginning her search for her home, realising just how difficult a task she had ahead of her. Money, bed and board were rarely an issue; she could sing for her supper, play fiddle or flute, arrange dances and teach the steps to a room of happy and, crucially, paying customers. No matter where she went she was confident she could exchange story and music for food and shelter, and often for coin or goods. She practised constantly, not just her music, but also her language skills, learning, adding to her knowledge whenever she could.

On the road she could hide her camp to avoid unwanted attention, steering her steps clear of any village that felt wrong, avoiding danger and trusting to her instincts. Yet she also knew it would be wise to pause to give birth.

Winter was approaching and a city was perhaps safer, a sensible place to stay. More people meant more money for less work; it was simple economics, as Rharsle had so often explained. Cities were where the most money would be made, where new stories and songs could be learnt or stolen from the competition, and where coin meant comfort; cities offered the opportunity for professional development in ways small towns or rural villages rarely could.

Her plan had been to find a comfortable and clean inn and stay there, playing every evening and perhaps twice on days of rest or ceremony. It made sense to have a base, for a while at least, and the more she thought about it, the more Flin knew it was the wisest thing to do.

A part of her was tempted to turn around and head back to the large town she had passed through just before she had discovered she was pregnant. The inn she had stayed at had been clean and felt safe, but the town of Hazelhill was perhaps too small for her needs; she wanted to find somewhere with a constant draw, somewhere which was either a centre of trade or well known for something else, attracting new blood, new customers, eager to hear her songs and stories and part with their coin.

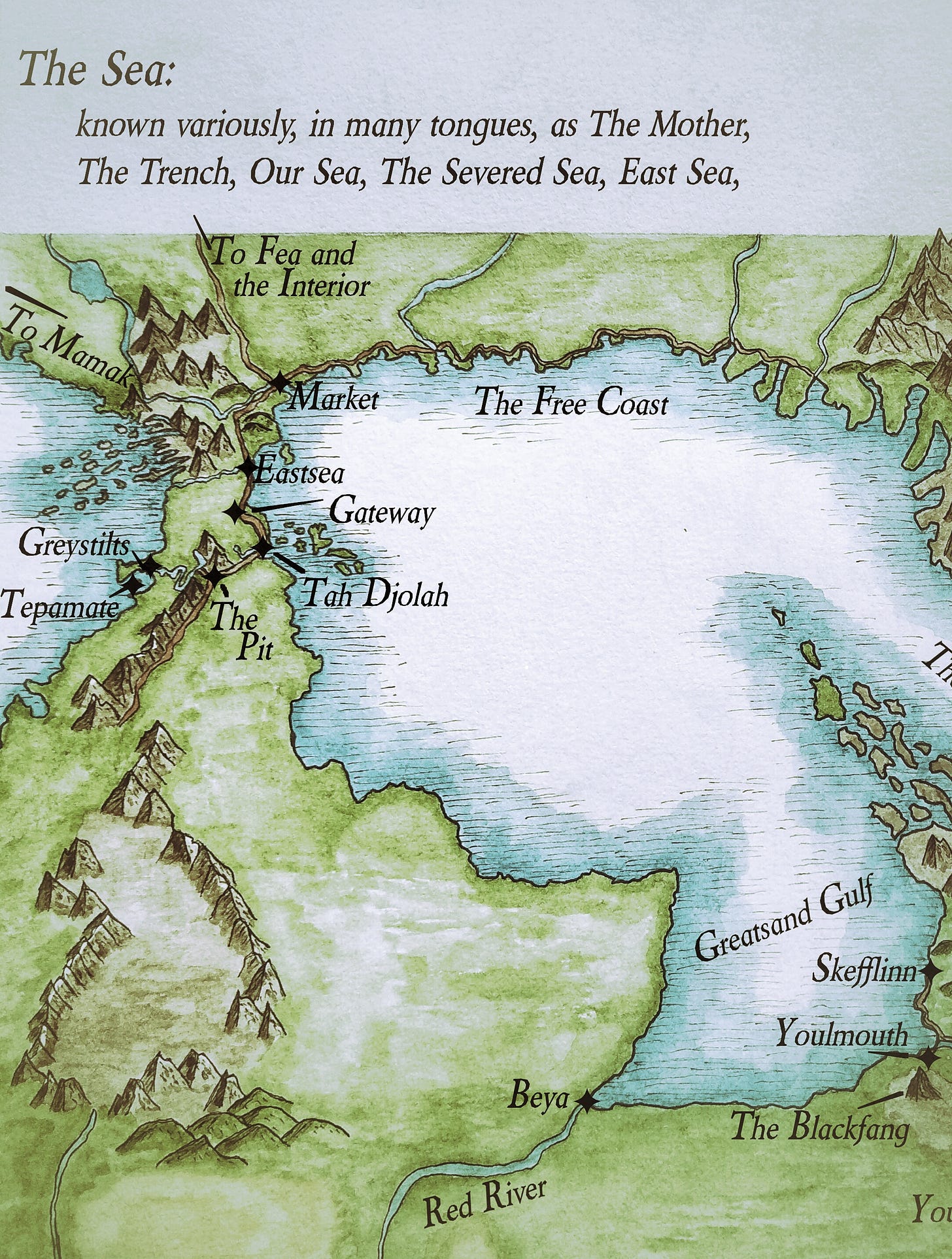

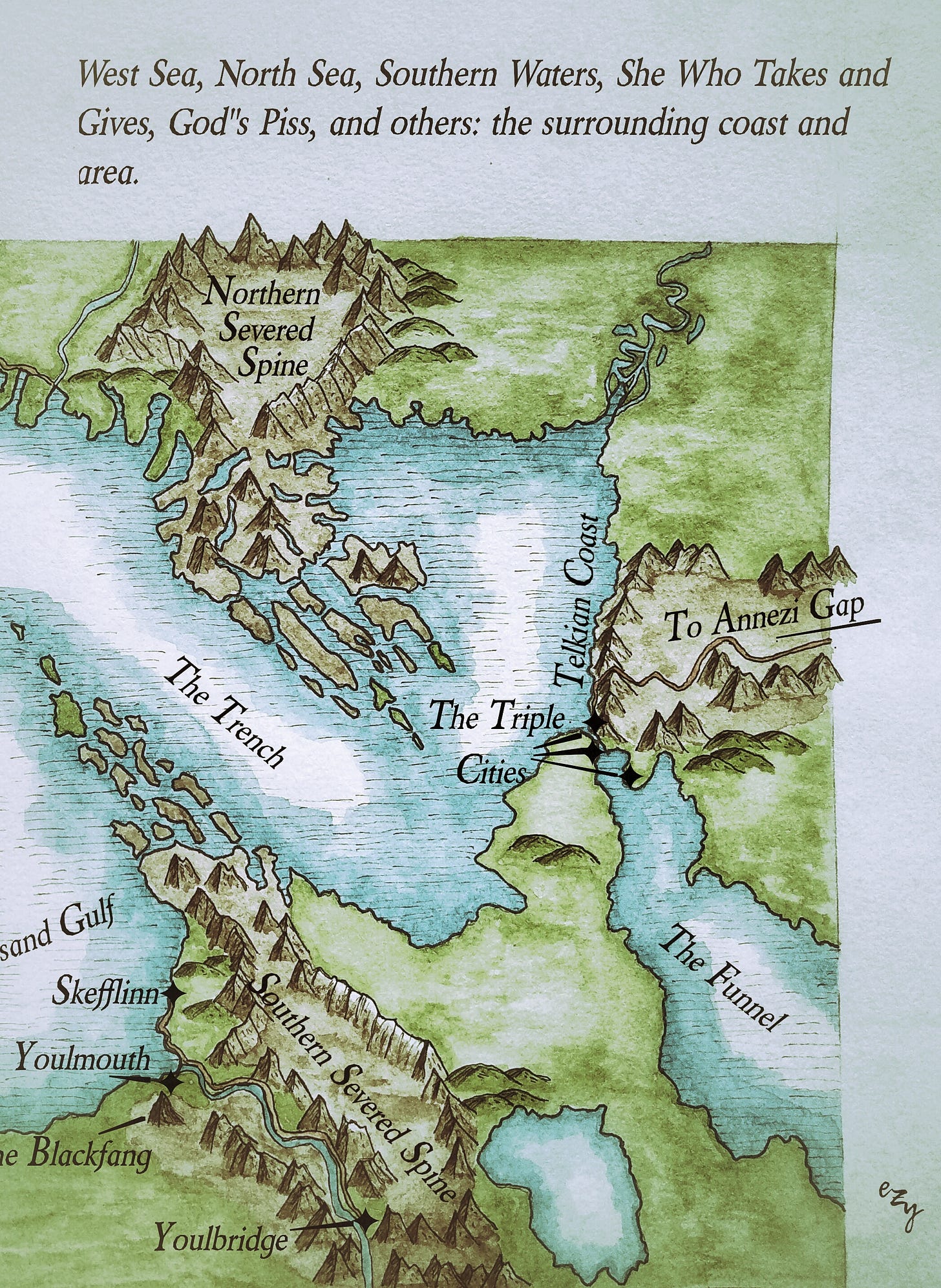

Flin even considered heading all the way back to the large port city of Youlmouth, but that would mean two months walking in the wrong direction. It did not seem right to go backward in her search for home. Instead she walked on, knowing that somewhere ahead on the road lay the city of Russetbrae-on-Youl, also called Youlbridge, also shortened to Russetbrae. Cities often had different names, she had learned, something which made finding her home that little bit harder than it already was. From what she heard, she knew Youlbridge would be a perfect place to rest for a while.

And, for a time, it was.

She arrived in the early fall, with the trees and loam scented with approaching winter, drifting, tumbling leaves dusting her during the day, and frosts sending delicate tracery across her cloak as she slept. Youlbridge was reached at just the right moment, with the first snows blanketing the mountains to the south and west and the broken reflection of the Hunter’s Moon dancing in the swift mountain river that gave the city its twin names.

In the years she had journeyed with Rharsle, Flin had never lost her sense of wonder. Each and every city was different and a marvel in its own way. Cultures varied, languages changed, even the races of the Talking People differed, but they all loved music and song, and those who played instruments, told stories, or sang were generally always welcomed.

From a distance, Youlbridge rose from the river valley like a vast outcrop, its walls blending with the local stratified rock from which it was quarried. Rooftops were mostly clad in thinner stone slates of the same material, often themselves clothed in moss and lichen. The city was angles and facets, thick wooden shutters to keep out the bitter winds and driving snows of winter, bridges and walkways were everywhere, each lined with a tall wall to ensure no one was blown off to the streets below. In places rooftops almost met above the alleys and narrow streets, taming the worst of the weather, preventing it from savaging those who passed below.

The city sat astride the Youl, which was navigable to this point, but no further, the docks were on one side of the city and swift rapids on the other, bridges, towers and even elevated streets braiding the flow of the river just before it met the flatter valley downstream. The whole was embraced by a tall city wall, the most complete set of defences she had seen, towers and turrets and just four gates to enter. A second set of walls encircled the docks, like arms extending from the city, welcoming the ships and barges.

The streets were some of the cleanest Flin had walked. Shortly after her arrival, she learnt that the city was built on the ruins of an older place, a place that still existed below, deep down, with whole buildings and neighbourhoods all buried beneath those above. Many of these old places were reused as sewers, the waste washed away every spring with the snow-floods, channelled through a clever network of tunnels, canals, and sluices. The guardians of the city, the Council of Eleven, would order the river to be diverted into overflows, which did no damage to the thick stone walls of the present buildings, as the water scrubbed away the build up of detritus beneath the streets.

Many other cities had old, damaged sewer systems, the money which should have been spent on repairs going towards vanity projects or good, old-fashioned corruption. Some cities had no sewers at all, just a polluted river, or coastline, or a reliance on rainfall to wash away the filth of thousands of people and animals living together in close proximity.

Youlbridge really was perfect. A clean place to give birth, safe behind massive fortifications, with trade flowing through the city gates and, with it, travellers bearing new stories and songs, heading to the Templelands, or into the mountains to the west, or north to Youlmouth. The road also continued south, but few passed that way any more.

Flin took barely any time to locate an inn, or rest-house, as they were known in the city. The pair of women who ran The Maze Fighter were better hosts than she had ever dreamt she would find. The inn was not as large as others but, being close to the southern gate, it was popular with travelling adventurers, whose requests for story and song were varied and interesting. It also gave her a chance to ask more questions, try and find clues as to where she was from, and work out where she must head once her child was born and old enough to travel with.

The Maze Fighter was named after the once-per-five-years games, in which the greatest fighters and craftiest thieves, the strongest and the swiftest, the most cunning, the smartest and, often, the greediest were attracted to the city, in search of glory, fame, and riches. After proving they were worthy through a series of tests and challenges, they drew lots and entered the underground places through one of four doors, named for the four tallest peaks surrounding the city. Then they were in the Maze.

The Maze was altered each time, walls added and others removed, traps laid, doors locked or concealed and some reopened. Creatures were imported, bred, hidden in dark places, and left hungry in the days before the games. Most of the tunnels and chambers that made up the Maze were blocked from the spectator’s view, but important junctions, areas full of interesting traps and beautiful treasures, angry and starved animals, confrontation zones, and a few other locations, were within cleverly-designed arenas, the walls of which were too tall and too slick to climb, but afforded the paying public fantastic views from above. A handful of these places even had thick viewing windows of very, very expensive glass or polished sheets of rock crystal, ringed by stalls, benches, and the din of the constant betting and cheering above. These areas were well lit below, so the spectators could always see the action, day or night.

There were no rules in the Maze and nothing was forbidden.

There was only ever one winner and, some years, there was none. The solid and ornate exit door, known as The Champion, was located in a final, huge arena, and only opened when there was a sole survivor. The guards who patrolled inside some of the walls, checking on the progress of the contestants, would often engineer a final battle, a winner emerging into the arena, blinking at the bright sunlight after many hours underground, ears ringing from the roaring crowds towering above them, only for the door ahead to be slammed shut and bolted as another entered, the two forced into one last battle. Sometimes, the organisers released a final, special creature into the arena, or waited until there were three or four fighters to fight one another. Alliances could not succeed.

When she initially heard this, Flin thought that it would have been the worst of ways to die—to see victory and freedom, only to have it snatched away. The guards shot any other survivors who arrived too late, sometimes they flooded areas, or released creatures from their designated zones. Only one winner.

The Maze Fighter stood within a bowshot of the exit to the Maze, The Champion itself being visible from several of the windows. For most of the five-year cycle, the inn attracted a certain clientele: merchants, wanderers, adventurers, those who were passing through the city. It was far enough from the more reasonable markets, cheap housing and even cheaper entertainment that it prevented unwanted guests of a less-than-desirable calibre.

For the last three cycles, the inn had housed several of the contenders for the Maze, which was both an honour and excellent advertising. It also helped that their oft-extravagant bills were paid for by the City itself, the whole process a vast business, bringing in coin and wealth, much of which was then reinvested in the following games, or into the city: repairing roads and public buildings, digging new wells, paying the local guard, and even funding not one, but two free hospitals.

Looking back later, Flin realised, those days, from her arrival in Youlbridge to when her child was six month’s old, were among her happiest memories.

The winter was cold, but the city did not suffer. The light snow that fell that year was cleared from the roads, which were then strewn with grit and crushed rock-salt from a nearby mine, a practice new to Flin. The innkeepers were pleased, less snow meant more footfall through the passes in the mountains, more footfall meant more money. Some years, the snows were so deep barely anyone visited the city for two or three months.

Food was plentiful, even in deep winter. Youlbridge had experienced generations of peace and the wise leadership of the Council of Eleven meant stores were laid down in times of surplus, maintained for those winters when the weather was harsh and trade routes were blocked.

The following spring the floods were less fierce than normal, briefer and passing quickly. The villagers and farmers along Youlvale were pleased, short floods meant they could plant earlier, perhaps securing a two-harvest-summer, as happened once every fifteen to twenty years.

Flin gave birth to Kadan, a strong healthy baby boy named for his father, surrounded by the kindness and affection of the innkeepers, Sarah and Mariea, and their four daughters, all of whom were incredible: supportive, kind, understanding and full of love. She felt immense joy at being accepted into their family, but also a deep sense of loss and sadness at the fear she may never find her own parents and siblings, Kadan’s family. Somewhere, out there, he had grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Yet it was reassuring and comforting to be reminded there were still good people in the world.

Then all that changed.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

Just so you know, I am still mad at you for this story and will never forgive you.

I love how you've written this story, interspersing the fear Flinn has when being chased with her contentment in Youlbridge and the desperate search for her home.

Also, thanks for telling us who her baby daddy is; I assumed it was Rharsle this whole time. :)