Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the eighteenth chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

She Who The Dark Fears

The Past: Youlbridge

Flin stared, open-mouthed. It was better than she had hoped for and more. For a moment she remained silent, then nodded.

‘Thank you.’

‘Not thank us. Thank the child. Without that, you would wander and you would die. It will not be easy for you even beyond the walls, the city is not the same as a sleep ago, plague and fire and death.’

She nodded again, unsure what to say.

They moved off at a walk, the low ceiling forcing Flin to bend over, and her back quickly began to ache. She began to wish she was shorter. Three of the remaining four of her companions moved in front of her, with the other some distance behind, guarding their backtrail and, as they walked, she studied them as best she could in the dim light. Rharsle had taught her how to look, how to observe and memorise and, in her head, she began a beat, a cadence, adding words to a new song to remember, to be able to record this moment and return to it later.

These people, the Tanuthian, wore hoods which covered their heads and shoulders, but no cloak which, she assumed, would catch and hinder them in narrow spaces. Since she had been underground, she realised the temperature had been a relative constant, definitely not warm, but not too cold. Perhaps it did not get cold. She did not know.

The woollen hoods mostly blanketed their features in shadow but, from the glimpses she had received, she had seen pale faces and wide, dark eyes. Below a shirt of what she thought was also wool, they wore knee-length kilts, wide leather belts encircling their waists. Hanging from each belt was a pair of large pouches, angled behind them, larger than those normally worn by those above ground. One hip held sheathed blades, a shorter knife beside a longer, the other hip carried a tool Flin was not familiar with, a thick cylinder of metal with what looked like a sheathed pick head at the top, a broad chisel point at the bottom. She guessed it was useful for digging, but had no idea what it was called.

Long-fingered hands looked to possess serious strength; they might be short, but they were powerful, thick calf muscles clear below their kilts, wide feet with long, splayed, toes, clad in broad, metal-studded sandals. They moved with confidence and grace, relaxed in the low tunnel, even as Flin struggled with the shuffling, hunched skip she was forced to adopt.

She struggled to get a better look at their faces. They kept their hoods low and the angle at which Flin was bent did not help. Her back ached; carrying Kadan, pack, quiver, and instruments, as well as the bow and lantern, was a struggle. Still, she told herself, it was considerably less of a struggle than being alone and eaten by something which had just seemed to be fangs and long claws, or wandering around until her fuel ran out, to die in the dark, lost and lonely.

Instead of complaining, she kept her head down and her legs moving, one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four. Her song began to take shape, the rhythm of the doubled-over march tying it together. She would not forget this tune.

They walked on, into the dark, turning this way, then that, and it did not take Flin long to lose all sense of direction.

‘You can take a short rest here,’ the Tanuthian said, before adding something else in its own language. Two of the others went on ahead, one dropped back further into the darkness of the way they had come.

Flin immediately sat down on the tunnel floor, here a fine, dry sand. She was exhausted, her back was agony, her stomach muscles tight, but she was also relieved she had guides, to know she would make it out of the underworld was a powerful source of strength and stamina.

‘I think I trust you,’ she said, as she realised it was true, and was rewarded with a small bow, a simple dip of the head.

‘Thank you. We place high riches in trust, in truth. Not far to go. Dangerous now, others walk beyond the door.’ He waved an arm in the direction they were heading.

‘Others?’

‘Those who bring the disease, those who bring the holy people and chain them.’

‘Has the plague badly affected your people?’

‘No. We get sick, but it is not like you. We get better. We do not understand why those who bring the holy people want to give disease to the Above. They know it is carried by the rats. When you go, do not tell others where you come from. Bad news travels faster than rockfall and chokesand, and talk of plague faster still.’

Flin was silent, thinking back to the chained monk she had talked to, the cages of rats, and the corpses of the others.

‘Who would do this? Why kill this way?’ she asked.

‘Games, human, games. You have your Mazes, you enjoy the death. Others, others with big power, they enjoy different games, with even more lives lost. Always has been, always will. We are but beetles and rockgrubs to them.’

‘Who? What others?’ Flin asked. She wanted to say that she did not enjoy death, nor did many of the people she had met, but it seemed unnecessary; there were still those who did, and too many of them.

‘Rest, feed and change baby. It will be long time running for you when you leave. Those on the walls shoot anyone fleeing. You must move fast before the great torch rises.’

Flin did as instructed, waiting until Kadan was latched on and hungrily suckling before she spoke again.

‘Who did this? Why?’

The Tanuthian hissed a little, moving its hand up and down, before it replied.

‘You ask many things. Who did this? She Who the Dark Fears. The Trapper. The Weaver of Lives. She started the Maze, she started this city. She uses the Above for power.’

‘A woman? A human woman? She did this? What do you mean, started the city?’ Flin was unsure what else to say, the answer to her question made no sense.

‘She tells others to do, to do this, do that, pulls them here, pushes them there, down this tunnel, up those stairs. She is not human, no. Not for a long age or more. Perhaps never.’

‘Who could I tell? Who could help?’

‘None. No one I think. You will never meet those who could aid. She is one who plays games higher than us. One of those who… last. Her games are long, tens and tens of our lives. We stay away from these games as we can, our people do not wish to be a part of them. Better to hide away.’

‘But…’ Flin began, but her question was cut off by the return of one of the other Tanuthian. There was a rapid exchange of hissing and clicking.

‘We must go. Fast. Others come into the way we need to use, we must go. Swift again.’

Flin tucked Kadan away and rose to her crouch, wincing at the pain and wishing she could continue the conversation. Soon, she told herself, soon she would be able to stand again, then she could focus on fleeing from the city. There would be a time to think, a time to ponder, but not yet.

‘Here you turn off light. We guide you, but light may be seen. Be silent, trust my hand and eyes. We know these places. It will not be long and we must be silent.’

‘Thank you. Thank you for saving us.’

‘Thank your baby. I told you, we do not save, we leave.’

Flin nodded in reply, blew out the lantern and attached it to her pack with two leather straps, so it would not rattle or fall.

‘When we take you to the outside, you will need to move fast. Follow trail into trees, do not take the road. Stay hidden in day and run at night is safer. Great torch will rise soon, so you must find place to hide swiftly. Now, we go and do not talk more.’

Flin felt her hand taken and held firmly. She kept her head down low and followed where she was led. After a short walk they stopped once more.

‘We open this door and we are in tall space. You do not need to bend here, we move fast. Ready?’

She nodded and heard a hushed scrape of stone as another door was opened. She could see nothing, but she was led with confidence and care. The low tunnels they had followed since she encountered the Tanuthian had been stone and brick passages, narrow and tiny, perfectly sized for her guides. This tunnel felt bigger, made by man. She wondered whether the makers of the Mazes knew of the Underworlders, whether they found their tunnels and wondered where they came from, or whether they did not notice or care. She was glad to be out of the cramped conditions and stifled a groan as she stretched her back, something clicking, popping and cracking, loud in her ears.

Then they moved. After a hundred steps Flin began to realise she could see, initially not much beyond a lighter patch ahead, but it meant she was reaching her exit. A short time later and she could see the shadow of her guide, alone now, the others somewhere ahead or behind, silently disappeared. A bit further, and she could make out the walls and floor. Further still and Flin could see where others had walked, heavy booted, human feet, drag marks here, ruts from a hand cart there. She felt her guide squeeze her hand, then draw near to whisper.

‘The trail is to the right, down. When you reach the fork, take the right route, keep going and avoid the road and all others. There are men behind us, coming out soon, now go.’ The Underworlder gave her hand another squeeze and made to leave, but Flin held tight.

‘Thank you,’ she whispered. ‘My name is Flin, Flinders Jeigur.’

‘Dal Wel Maniker Fye. Go with speed and surety Flin Flinders Jeigur.’ Then he was gone, one moment there against the wall, the next pushing through another hidden doorway.

Flin did not wait, immediately setting off for the promise of freedom held in the patch of grey light ahead. She tightened the straps on her pack, her shoulder bag and Kadan’s sling, drew an arrow and a deep breath, then ducked out into the dying night, the first hint of dawn already blushing eastward.

She listened carefully, but could hear no one along the trail ahead. Behind her, above and behind, came the crackle, crunch, and roar of fire, calls and panicked shouts, the screams of terrified horses, bellowing of cattle, the chiming of bells, all eddying in the breeze, bringing smoke scent and scorched air with them. Looking around, before she entered the thicker tree cover, she realised she was where Mariea had told her she would exit, on the eastern side of the city, a double bowshot from the Sunrise Gate. She had travelled a much longer, more dangerous route to make it than she had intended.

Mariea had told her to head to the road above and to her left, and keep going, but that had been before the fire, before she had learned of the guards shooting anyone leaving. Flin felt she could trust the Tanuthian, and picked her way through the rocky, scrubby tumble of the slope above the deep gorge of the Youl, eyes now accustomed to darkness easily picking out the faint trail.

Then she was amongst the trees and moving confidently, pausing every hundred steps to listen for a few deep breaths, before continuing. The trail led along the hillside, hugging the ground and initially neither going up nor down, before it began to climb.

At a gap in the trees, Flin paused: something had changed. It took a heartbeat to realise it was flickering light reflecting off damp tree trunks, light from behind her, opposite the dawn. She turned and looked and her mouth fell open at the sheer scale and horror of Youlbridge burning.

From this distance, she could see that the whole of the Sunrise District was on fire, strong winds fanning the flames, the nearest buildings and city wall silhouetted black against apocalyptic red. It was horrific, it was terrible, awesome, mesmeric and strangely beautiful. The clouds reflected the glow, a dull, sooty orange covered in sparks, as though a billion fireflies danced in the night.

She could not help but wonder if Youlbridge would survive this. Plague and fire both, a pairing which may kill the city, or may cleanse it to be reborn. She knew of other places, other songs, where ruin only led to renewed growth. Could the city rise from the ashes, or would it become less, nothing but a memory of a moment in time. She knew those songs too, often no longer tied to a known place, only the words and tune remaining, sometimes even the name long gone. On her travels she had found many such dead places, whole villages abandoned and ruined, towns falling back into nature, their songs silent, lost as their people were scattered, or worse.

She returned the arrow to the quiver and removed the bowstring, coiling and placing it in a waxed pouch, before hiding it away in a dry inner pocket. The air was damp and keeping the bow strung would risk damage.

It was hard to turn away from the terrible view, but Flin forced herself to move along and quickly came to the fork in the trail her underworld guide had mentioned. She did not hesitate, taking the clearly less-travelled lefthand route, still hugging the slope above the gorge. Finding tracks and roads was easy for her, they seemed obvious where others often lost them, all roads except the one which led home.

Her mind concentrated on the task, one foot in front of the other, listening every so often and sniffing the air, checking in front and behind, but it seemed there was no one else on the path. The Youl below took a turn to the south and she found she could no longer smell the smoke, although it still towered over the hills behind her, thick and high, before scudding away east and merging with the clouds.

Mariea had told her to take the road east and then south, before switching to the higher pass back north, skirting the city through the meadows and farms which stretched along the valleys and slopes west of the Youl. Head to Youlmouth, she had said, then take passage anywhere she wished.

Flin was unsure whether this was still a wise plan. It would mean crossing both the river and road, risking patrols, even in the upland farms, and she did not truly want to return to Youlmouth—it seemed a backward step.

The alternatives would take her and Kadan away from Youlbridge faster, if by more dangerous routes. After the junction to the western hills, she knew the road continued south, following the Youl for a day’s walk before it split, one branch crossing the river and continuing south-west, shadowing the flow, the other heading east, up into the Templelands. She did not know where the river came from, few people had travelled that way for a generation and it was said something dangerous and powerful had claimed the area as its own; what, she did not know.

The Templelands were dangerous in their own way, tiny mountain kingdoms, each with a temple complex at its centre, each devoted to a different way of living, a different deity. Some were as small as a single valley, with a village or two and perhaps a dozen devotees, others were holy fortresses, commanding a pass and multiple valleys, with several towns supporting them and many hundreds of priests and adepts.

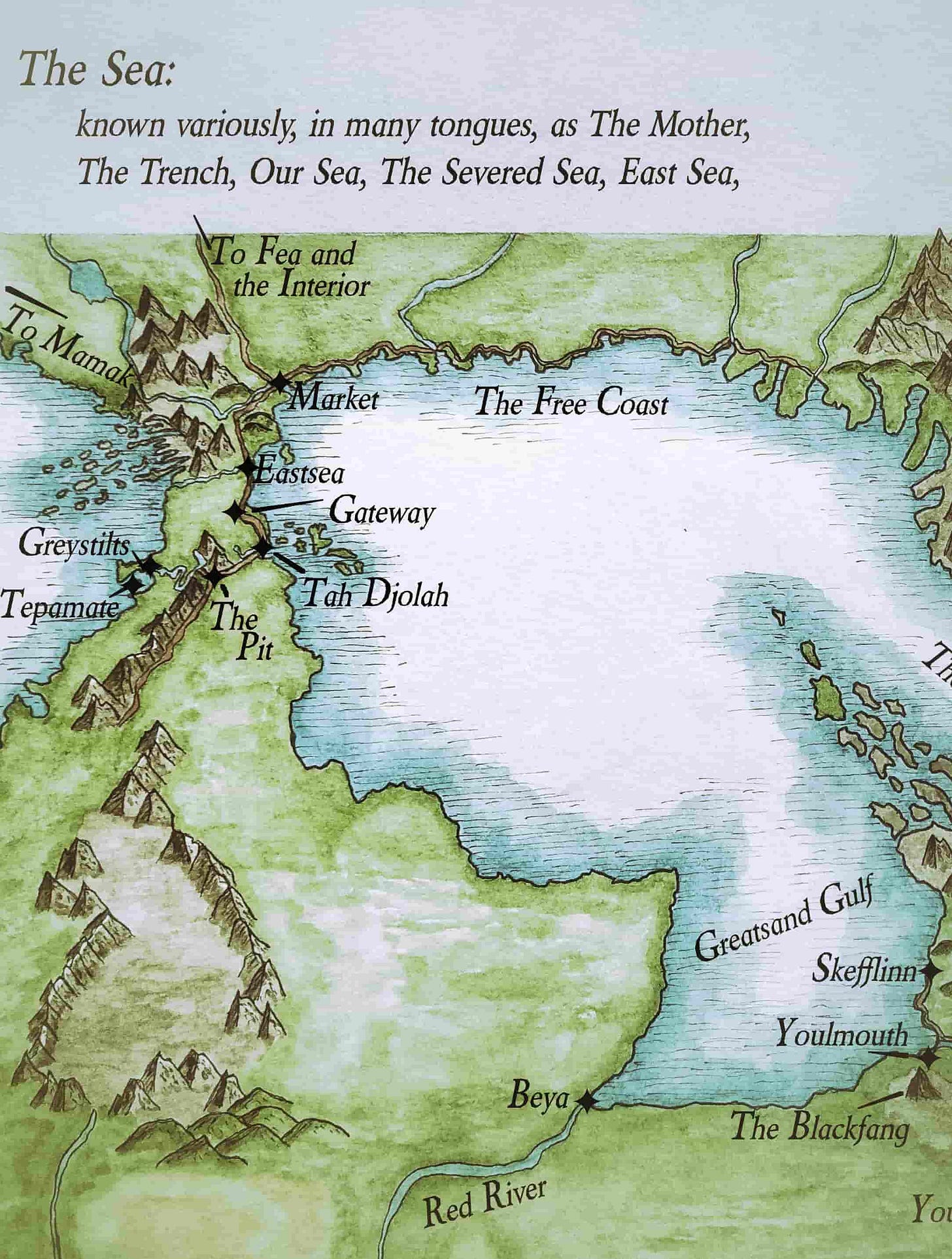

Different religions and different rules meant different dangers, yet a woman with a baby, a performer with a baby at that, would surely be safer than the average traveller. Flin was unsure what lay beyond the Templelands, although she had heard there was a vast lake, teeming with life and supporting many large settlements. Beyond that, a long journey to the coast and Funnelside, from where she could take a ship, perhaps north and west, to Eastsea.

‘I think we go that way Kadan, what do you think?’ Kadan, as was usual for the baby, did not reply.

Flin felt a momentary thrill at the thought that, one day in the coming months, he would reply. There was so much she longed to teach him, to share, not just the songs and tunes which gave her life meaning and purpose, but also how to find safe water to drink, how to harvest an ants nest, how to stay warm or stay cool, all those things she had learnt on her travels, all those tricks and skills to stay alive, in a wide variety of environments.

She drank from her nearly empty waterskin and sighed. She was tired.

‘We will go to the Templelands, little one.’

The wind swirled and eddied, bringing with it a stronger scent of smoke and a raised voice. Somewhere, back the way she had come, a man was talking, close, too close; Flin ran.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

I'm really intrigued by Kadan's significance....