A Certainty of Death

Death In Harmony: Part Twenty-Three of Twenty-Nine

Death In Harmony is the fifth in the Tales of The Lesser Evil and this is the twenty-third chapter.

Skip to the story by clicking here.

This is a fantasy series—not quite grimdark, but dark nevertheless—with complicated and believable characters doing their best to survive in a world simply indifferent to their existence.

To read an introduction to this novella, and the backcover blurb, click here.

If you love the story too much to wait each week, you can also buy the ebook of the novel, as you can the preceding four Tales (available in an omnibus edition).

If you enjoy this story and aren’t already subscribed, please consider doing so:

share this with those you know,

or like, comment, or restack on Substack Notes.

A Certainty of Death

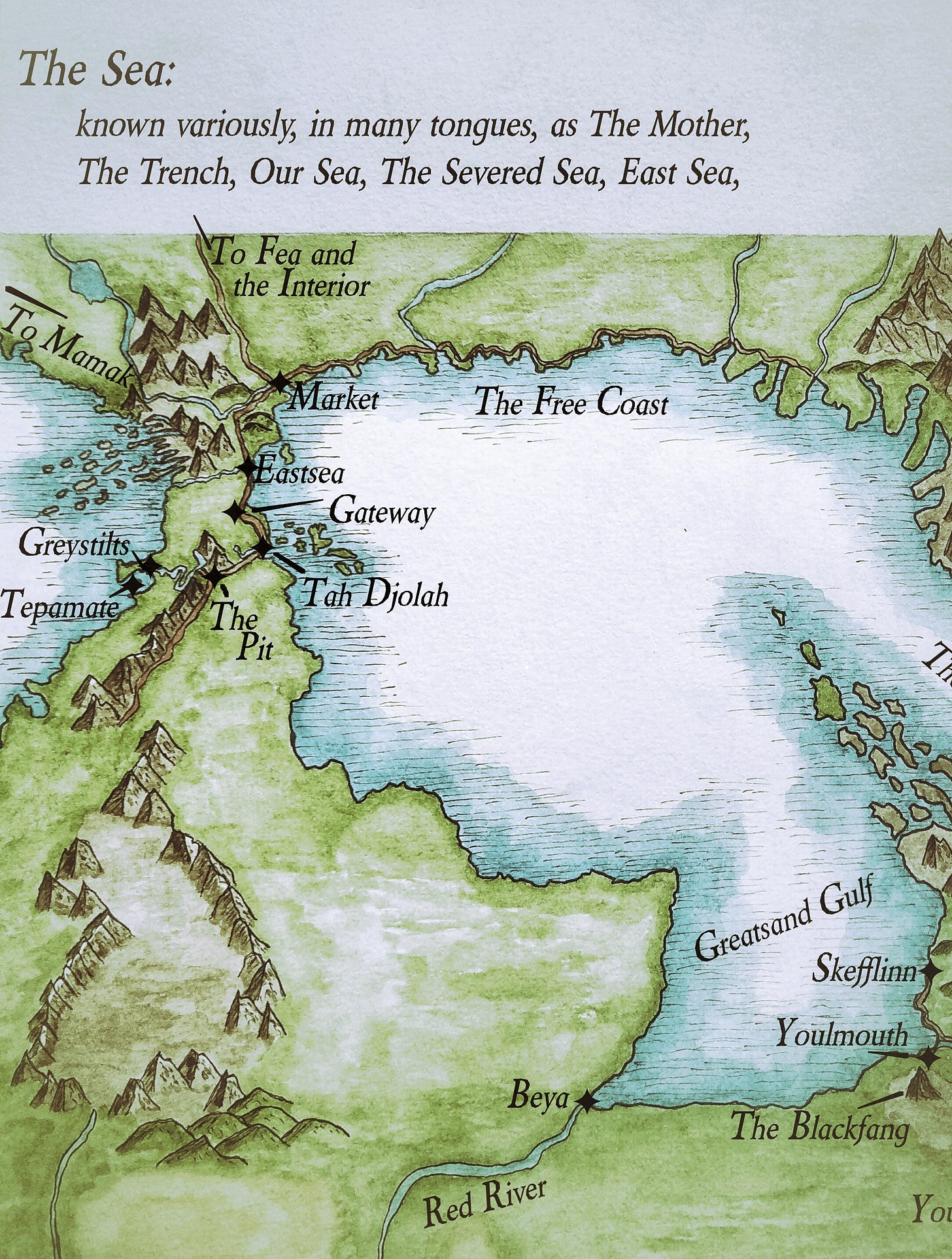

The Past: east of Youlbridge

The sloped streets and tall stairs of Youlbridge had strengthened and challenged Flin’s legs, after too long spent in the flatlands. She was glad of this; the trail she followed went up and down and up again, running high above the thundering gorge of the Youl, hidden below.

The deep cut on her arm was a dull ache, her lungs tired and heaving, her legs at times no longer felt like hers—she needed to rest, and to rest soon.

She had not bothered to drag the corpses off the trail. There seemed little point; even a child would have seen the disturbance in the soil, found the blood, deep drag marks and heavy footprints, heels pushed hard into the ground. Instead, she had simply left them where they lay, moving as swiftly as her exhausted legs could carry her. She knew there could be others following her, but there was nothing she could do about it, beyond keep moving.

The air was damp and Flin was sure she would have tasted forthcoming rain, had her tongue not been constantly coated in the acrid smoke of the city. She hoped it would rain, rain would help put the fires out and, more importantly for her, it would help hide her trail.

The trees were thicker now, clinging to the steep slopes, roots questing over rocks, where they could find no way down into the earth. At times it was difficult to separate the two, each moss-blanketed and lichen encrusted, the edges often blurred, hidden by loam and last year’s leaves. A mosaic of life.

Flin had seen no way down into the gorge, no trail joining hers. She knew it was unlikely she would meet anyone on the trail: the road was easier to travel, and no one would be leaving the city in the daylight, no one heading there, unless they did not know it was sealed and had somehow missed the vast banks of reeking smoke overhead. Still, she desperately wanted to find cover, somewhere to refill her water supply, wash the blood from her skin and clothes, drink deeply and sleep deeper.

‘There is nowhere to get down,’ Flin muttered to Kadan as she walked. She paused, held on to a mountain ash and leant out to look into the gorge. She could not see the river, the way the rocks bulged and the trees vied for light meant it was still hidden. ‘No way at all,’ she said and began to push herself back, then paused. Below, perhaps twice her height below, and at first invisible, was a faint trail.

It did not look wide, nor did it look easy to reach, but it was a trail, and it went down.

‘Do we risk it?’ she said, her eyes casting around for a way to get down but, beyond climbing, there did not seem to be any other way. Maybe she had missed something further back on the trail; she glanced back the way they had come. It was a difficult choice, return, or go on, watching the path below get lower and lower, until there was no way she could get to it.

‘We go back,’ she said, ‘If I missed it, others would too. We need to sleep—I need to sleep.’ Kadan murmured against her in reply, which she took as tacit agreement.

This time she was careful to leave as few footprints as possible, trying to walk not on the trail, but skipping from rock to rock, root to root, as best she could. She knew her subterfuge was imperfect, but it was better than nothing. Every so often, she would look down, to see if the way was easier.

They backtracked about a third of the distance she had already covered before the narrow path below became almost accessible. The drop was barely her height and, by using two prickly but solid holly bushes to hold on to, Flin was able to scramble her way down. She hoped the route led somewhere and was not simply a deer trail which eventually rejoined the path above.

It was slower to travel on the narrow ledge. With every step, Flin was very conscious of the distance to the river on her right, how a slip here would be fatal. Every so often, she spotted clear evidence of deer, goats, or sheep, and guessed the trail had been made by them, rather than people. The thought was reassuring. She knew the gorge here was wider than further upstream, where the Falls of Alvidra channelled the flow into a narrow spout, the famous bridge high above the plummeting chute of water, carrying the road to the south and west.

‘Let’s hope we can get up before the falls,’ she said, stroking Kadan’s head with her free hand.

Down and down they went, the roar of the river getting closer and closer with every step. The first few drops of rain began to fall as the trail levelled, still some distance above the high water mark of the channel below. Flin guessed that, with the melt-water in spring, the gorge would be a torrent, carrying trees, boulders, and anything else unlucky enough to be caught up in the crashing waters.

After a short curve, Flin walked into a wide, natural amphitheatre, a bowl cut from the rock on all sides. There was a level area with a rock sand beach, tangled with driftwood and strewn with detritus and, behind this, tucked upslope under an overhang of rock, was a cave mouth.

‘This is exactly what we need little one, exactly.’ Flin could already feel the warmth of her blankets and a fire, a hot drink and food in her belly and her sleeping baby beside her. She smiled, perhaps someone, one of the Gods of luck, was themselves smiling down on them, after all.

She picked up her pace and almost skipped into the cave. Too late, she remembered her childhood in the foothills and forests, and how many times she had been told to never, ever, go into a cave unprepared or unannounced. She skidded to a halt on the beach, right in front of a neat and clear set of tracks heading into the darkness of the interior. A large cat, heading in, but not out: a very large cat.

Flin began to back away, her hand reaching into her pocket to take out the bowstring, before a deep cough froze her to the spot. The darkness parted, revealing a wide, tawny head and a thick, luxurious mane.

‘Fuck,’ she whispered.

She had only ever seen a lion this close once before, and that had been at the vast market in Annezi Gap, safely secured behind thick iron bars. Who would have bought such a creature, she did not know, but she had felt sad to witness the sagging, once-proud head, covered in scars, one eye missing, the other dull and unfocused, its fur had been damaged, as though eaten by moths, and Flin had known it did not have long left to live. It had been old, mistreated, and ill.

The animal standing in front of her, mouth slightly open, pink tongue visible, tasting her scent, was nothing like the other. This was tall, covered in fur which shone with health, both orange eyes bright, sharp and focused in a wide head, thick muscles rippling with every small movement. Its paws were huge, the tail behind held straight out, like a rudder on a boat, a tuft of black fur at its tip. This was a creature at the height of its power, confident in its ability and ferocity. The mouth opened further, sharp and strong teeth parting.

Flin knew she could not string the bow and nock an arrow in time and she was sure the lion could easily leap the distance between then in one bound, as soon as he chose. She was going to die. She knew it, with no doubt at all. Yet, instead of bringing terror, she simply felt a deep, deep peace and time slowed, lazily turning over into something else, something bigger than her, larger than fear. In a corner of her mind, she wondered if she had endured too much over the previous night, that she could somehow no longer function correctly. Where was her terror? Her mind was blank, clear and calm and, into this space, came a distinct memory.

‘If you can’t make it, fake it, Flin,’ Rharsle’s whispered voice was close to her ear, the scent of the smoky room clear in her memory. It had been her first time telling a story in front of an audience and she had frozen in panic, playing the fiddle, or her kora, or even singing was one thing, but a story? That had felt like another level of performance, everyone hanging on her words alone. ‘They do not know you are scared, they do not know you have not done this a hundred times before. Just pretend, it is what we all do.’

The memory was strong, and Flin surprised herself by laughing out loud. She drew an arrow and pretended to quickly fit it to the stringless bow, then pointed it at the lion, still laughing loudly, willing it to go.

She took a step forward and it fled, spinning on its hind legs and leaping away faster than she had thought possible, tendons straining, tail outstretched and waving from side to side for balance as it swiftly ate the distance with long bounds.

Flin fell to her knees, her laughter turning to tears, then turning to a loud, wordless, undulating scream. Rharsle would have flicked her ear, telling her to never scream, never risk her voice like that. It was the first time she had done so in years and she felt a floodgate of emotion opened without warning, everything that had happened to her suddenly breaking free and pouring out in one long, wrenching, shuddering howl.

She wiped her eyes and dripping nose on her sleeve and stood, feeling oddly embarrassed and, less oddly, deeply relieved.

‘Well,’ her voice broke and she took another breath before continuing, ‘Well, I’m sure no one listening would have thought that was a person. Let’s check the cave and get a fire going, just in case your furred friend comes back.’ Kadan looked up at her, eyes wide and bottom lip protruding and slightly quivering, as though he too wanted to cry. Flin realised it was the first time her son had heard her scream, or even raise her voice, ‘I’m so sorry little one, I didn’t mean to scare you, just, you know?’ She was unsure he did know, but kept talking as she strung the bow, lit the lantern, and nocked an arrow—for real this time.

The cave went back only a short distance, but it was dry and sandy, with a clear depression where the lion had been resting. Soot covered parts of the rock, with partially-burnt logs scattered here and there. Flin guessed the cave was used occasionally, but had perhaps been flooded a moon or more ago, when the river had been at its highest in the spring melt.

It did not take her long to gather the burnt logs, bring in a stack of the driest driftwood, and light a fire. Then she set about making a camp, for the first time since she had given birth. Old habits and routines were so ingrained that she soon had her blankets ready, food cooking, and a hot tea at hand as she fed Kadan and, within a short time, they were both asleep.

Many thanks for reading.

Go to the next episode here.

Go back to the previous episode here.

Head to the introduction and contents page here.

Or read more about my fiction here.

The Falls of Alvidra!