November is usually a time of grey, of bleaching and the last of the chlorophyll leaching away as winter drags her blanket over all. Some stubborn leaves remain, to fall later in gale or frost, others have long gone, tumbled to drifts or pulled by rivulets into streams into rivers into the ocean. Everything is muted: burnt sienna, brown madder, burnt umber, brown ochre; names from the paints and pencils of childhood.

Yet, here , in the Alentejo, the opposite is happening. Summer was the browning, the hot sun and months with barely any rain drying all, water only available to those with long roots or clever placing near the streams and seeps. In the last week of October, with every passing day and, at times, hour, the hillsides and fields have greened: from olive green, through cobalt green, to the brighter sap green, avocado or mint, punctuated with the acid flash of citrus or the vibrant arc of a rainbow. These new shades are washed over the view, the land absorbing the rain and mist and cloud, the plants responding.

Our skies are no longer clear and blue forever, instead there are storms and showers, constant rain or sudden, tableaux of clouds and tapestry of greys across which are swept returning storks, our resident Bonelli’s eagle, or wintering hen harrier and red kite. Breakfast has become the time for birding, each morning seemingly providing a new sighting, something from the north, a snow bird seeking sanctuary, replacing those who have decided a sojourn in Africa is sensible.

The daylight hours are fading, true, but when I see photographs posted on twitter of a setting sun in the UK, I am reminded that we maintain longer winter days than much of Europe and, for that, I am grateful. Sun is a healing power to me, especially in the darker months.

The air is laden with the scent of wet earth, infused with growing things. The days of eucalyptus tang and drowsy cork oak warmth are gone, replaced by a wildness, a primeval sense of nature in charge, new growth and new, old magic. Spells whisper at the edge of hearing, each new blade of grass or tendril of vine carrying another word, another verse, and soon the emerald enchantment will be complete.

Hello

Well, this year has already lasted several millennia and it’s only November. It may be perverse and not-exactly-normal, but I actually like this. When time is s t r e t c h e d, then we are reminded what an incredible gift life actually is. We are born with this blank slate of indeterminable length ahead of us and what chalks we choose to record and decorate our personal stone is a marvel. It is never as easy as saying “we can do whatever we want with out lives”, that is far too simplistic and I have neither the space nor time to discuss all those variables which impact our lives but, what I can do, is acknowledge how often we waste time, how often we kill it.

The idea of killing time should be abhorrent. It is not time you are killing, but your own seconds, minutes, hours. It is not logical, yet we all do it. Again, the arguments as to why are too long for this space but, suffice to say, a part of it is the fact our brains need downtime to process things, to recover.

In my native UK there is a culture which revolves around a strange sense of pride in working yourself into the ground. Rest is viewed as for the weak, sleep is for losers, you can sleep when you are dead, and so on and so forth. If you proudly state how you got eight and a half hours sleep last night, you are viewed as odd but sleep should not be seen as wasted time. Rest is not killing those hours and days, certainly not when compared to some of the ways we find to spend this precious resource.

This year, for many, has been a long pause, a long recovery and ordeal both. I doubt there are many whose plans were not affected in some way, shape, or form and, I suspect, the coming months may well see things worsen still.

This was supposed to be the second newsletter you received this month, the first had been planned for the 2nd, the day before the US election. It was (is — as it is fully drafted) an examination of the idea of story as spell, the notion of a novel as prophecy, and fiction as a way to examine possible futures. In it, I discussed my own work, but also that of others (William Gibson got a mention or two), then went on to a long and drawn out personal analysis of why the world is currently where it is.

I decided not to send this. I suspect people are a little weary of individual takes on America, or how much influence other players in the game of politics have. I guess they do not need to hear yet another explanation that the climate doesn’t really give a shit about geopolitics, it just is, and it shall just be. I have hope, I always do, but I also believe there is a very high chance we will not get our collective act together in order to reverse, halt, or even slow the rate of climate and environmental decline and degradation in time to make a difference.

Perhaps I shall edit and send this piece at a later date, but perhaps not. Sometimes I write something and it is never read by others, yet the very act of writing helps condense and collate my thoughts on the subject, in such a way that it can then be woven into my other work. My stories are just that — stories — and I want them to be able to be read as nothing more than entertainments, as Graham Greene called his lighter work but, unlike Greene, I am happy to confess I work in important ideas into these tales. Not in a way that you might even notice, but I like planting the seeds of messages, placing small slivers of What Really Matters into a damn fine tale. The long, and often highly-political pieces I write for myself are just a small part of this process.

This month has been very very busy, mostly with paid, day job work and, of course, refreshing election results every twenty seven seconds. I have a feeling the coming months will continue to be similarly busy, but I am hopeful that at least, by the time you read this, the time for refreshing those figures will have ended.

Free Books!

I had applied for two different group promotions for November, but one was sadly full. As it happens, this was probably a good thing, as it was due to be associated with the above-mentioned essay. As it is, I am part of a giveaway over at StoryOrigin, along with an outrageous 100+ other books, all for free during November!

Next month I am also enrolled in a giveaway, which runs until the 1st of January, 2021. This reminds me how much I still have to do before next year, and how I cannot rely on time stretching when I’d like it to. It would be nice to be able to manipulate time, but I suspect I am at its mercy like anyone else. As it is, I am also hopeful I will finally make a copy of Death & Taxes (and the bonus, A Clean Death) available for reviewers. I will contact those of you who have let me know you would like to be a part of my review team as soon as I have a definite schedule. In the meantime, if anyone else would like to be a part of this team, just reply to this newsletter and I’ll add you to my list.

On Keeping Notes

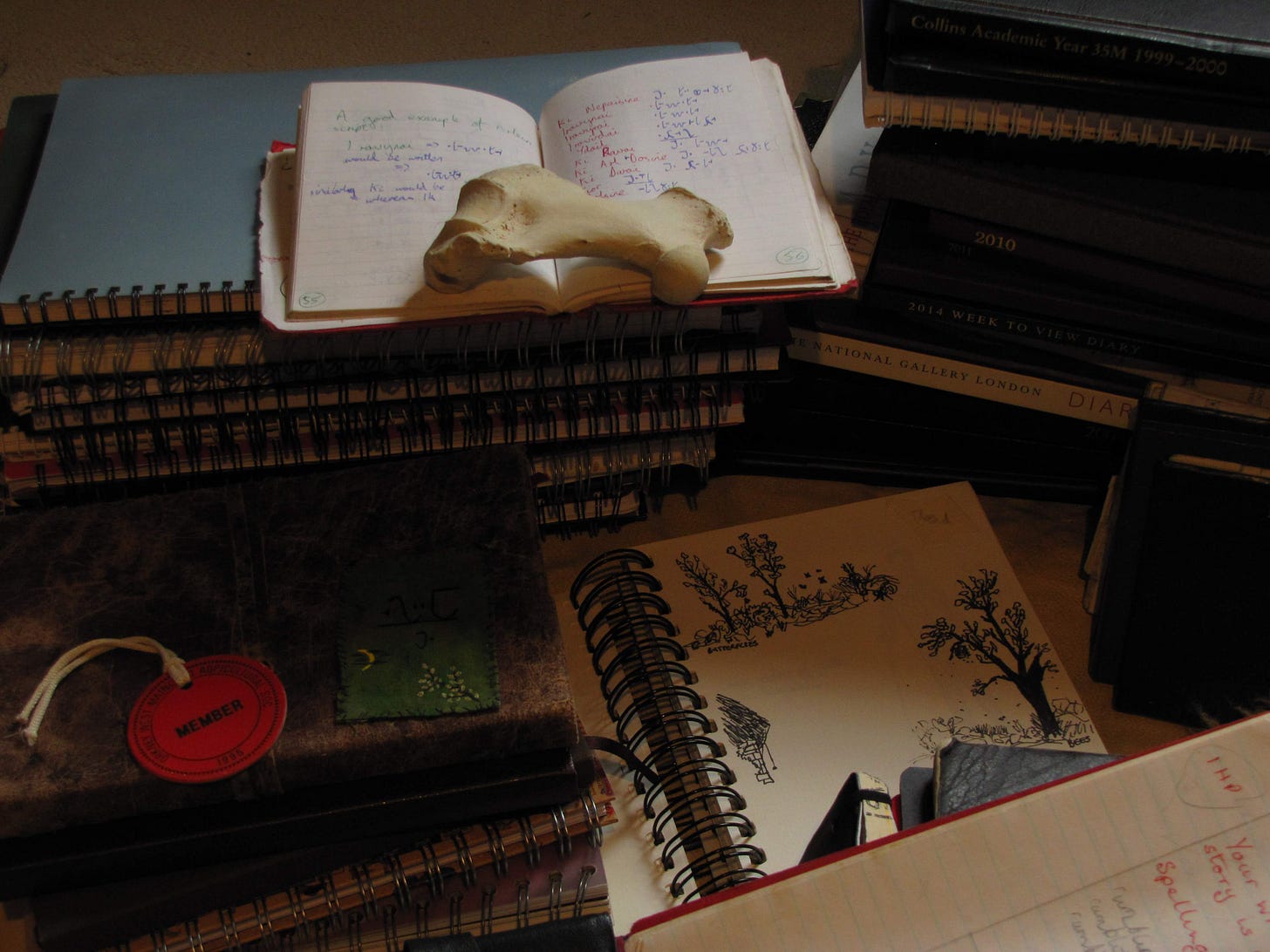

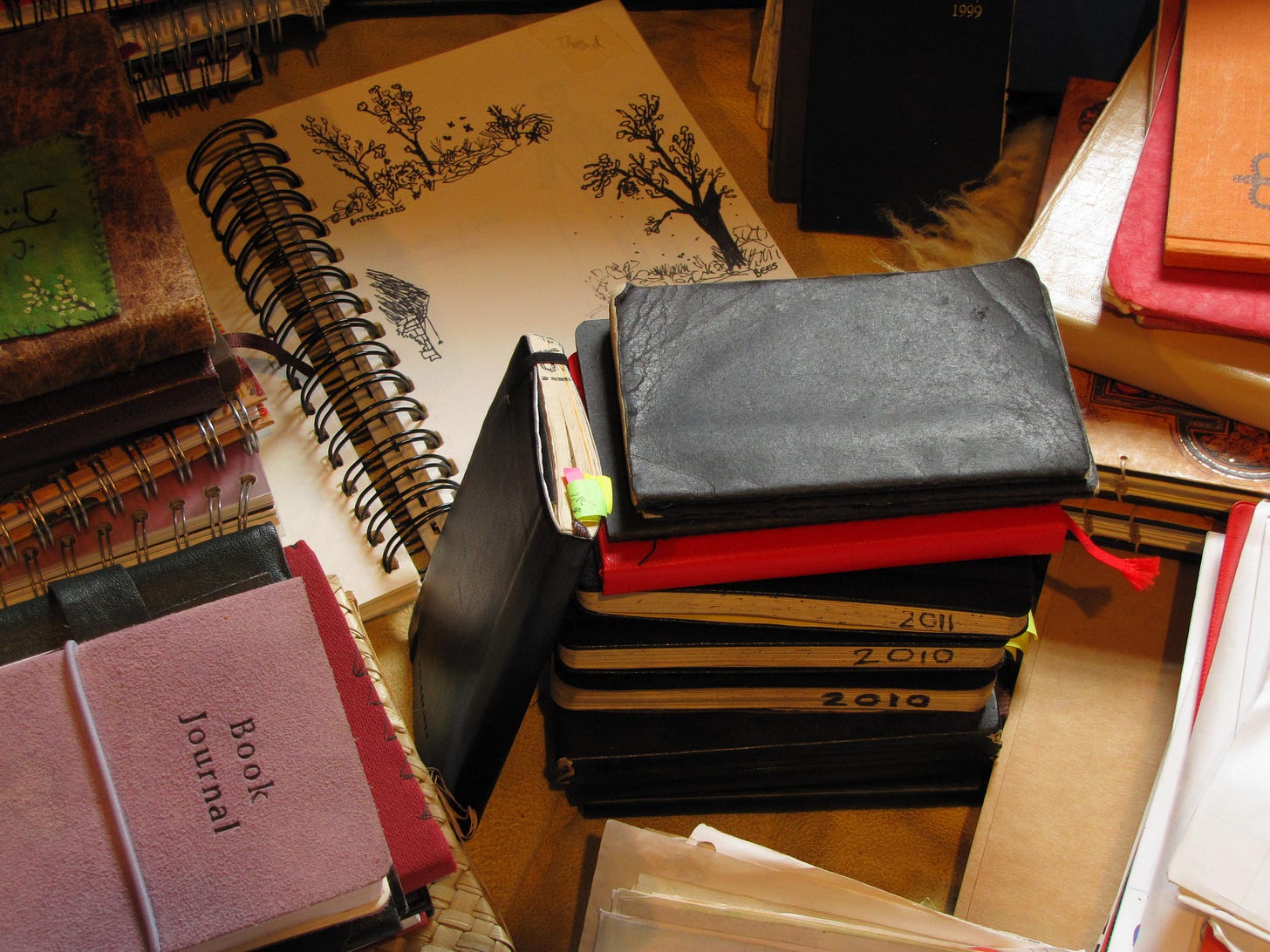

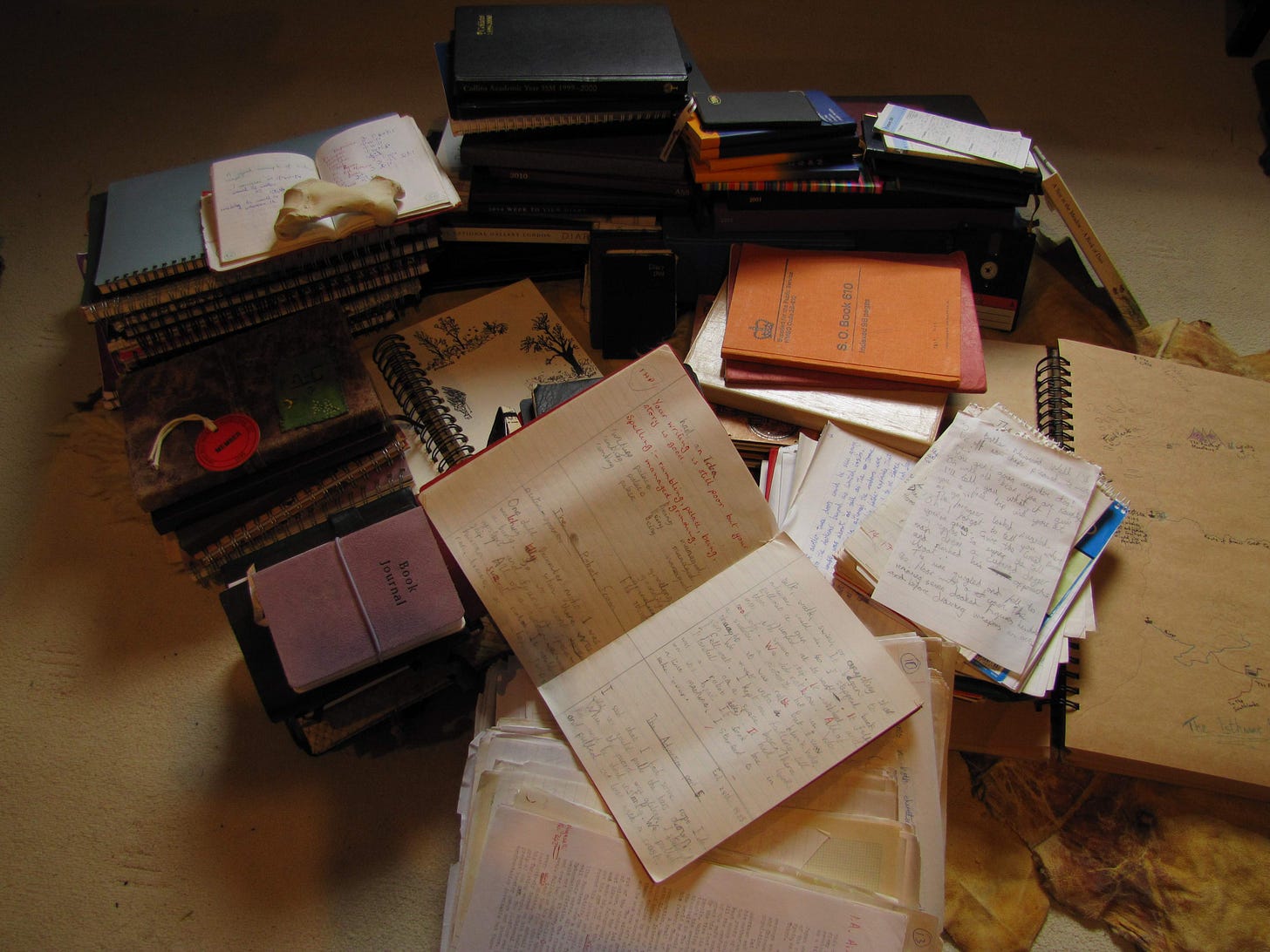

I am at the end of a notebook. There have been times in my life where a notebook barely lasted a month, but my current effort (Lemome dotted grid, cork cover, a gift from my sister Lydia, and family) has been in use since it was gifted to me in May 2018. At that point, we lived in Thailand, but were on a camper van adventure through France, whizzing through England, and then up into Scotland. We had no thought or intention of moving to Portugal. Now, I suspect there’s a realistic chance that the cork came from somewhere in The Alentejo. There is even a cork processing factory on the outskirts of our village. Maybe it came from an oak I know. I like that thought.

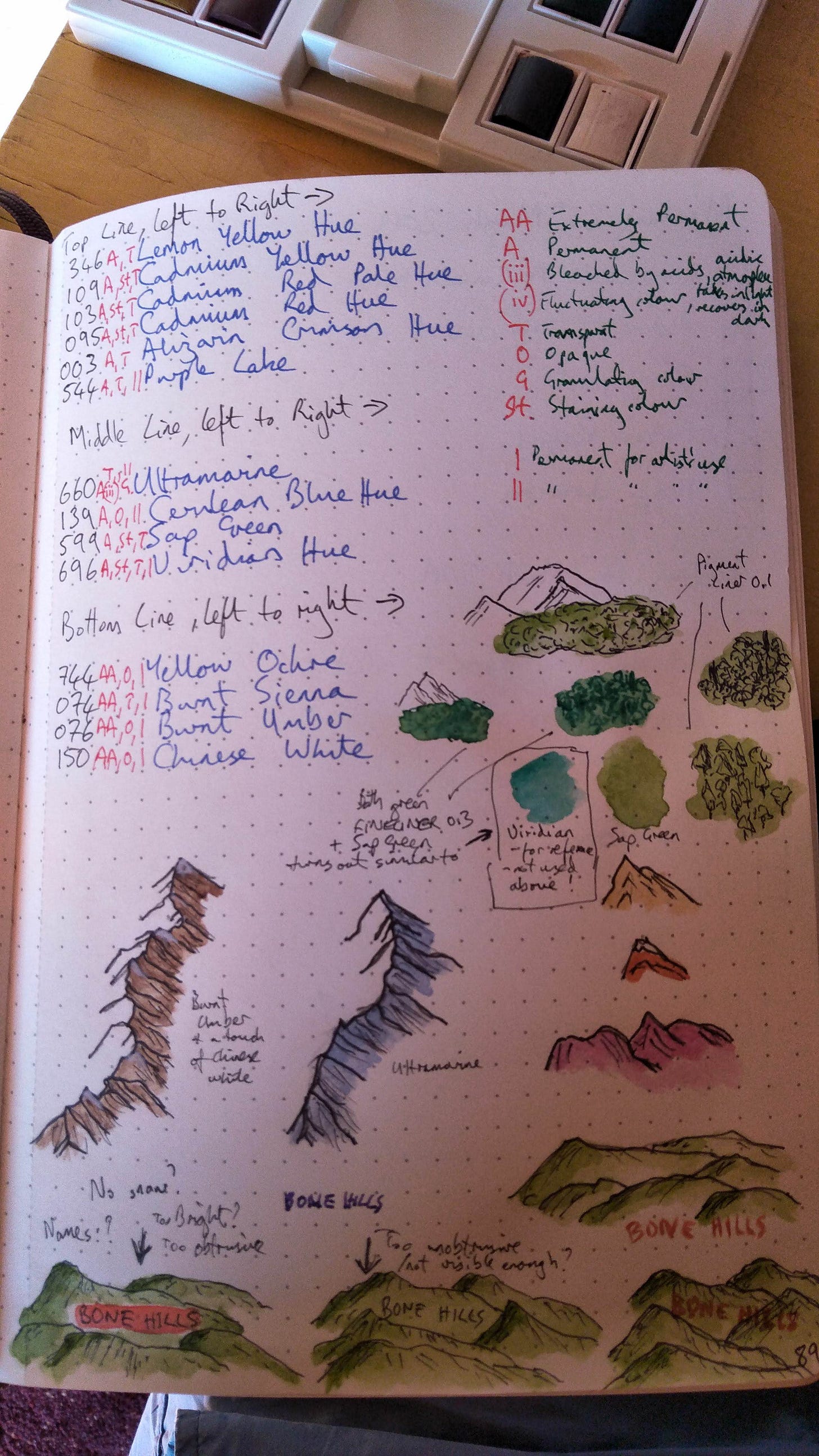

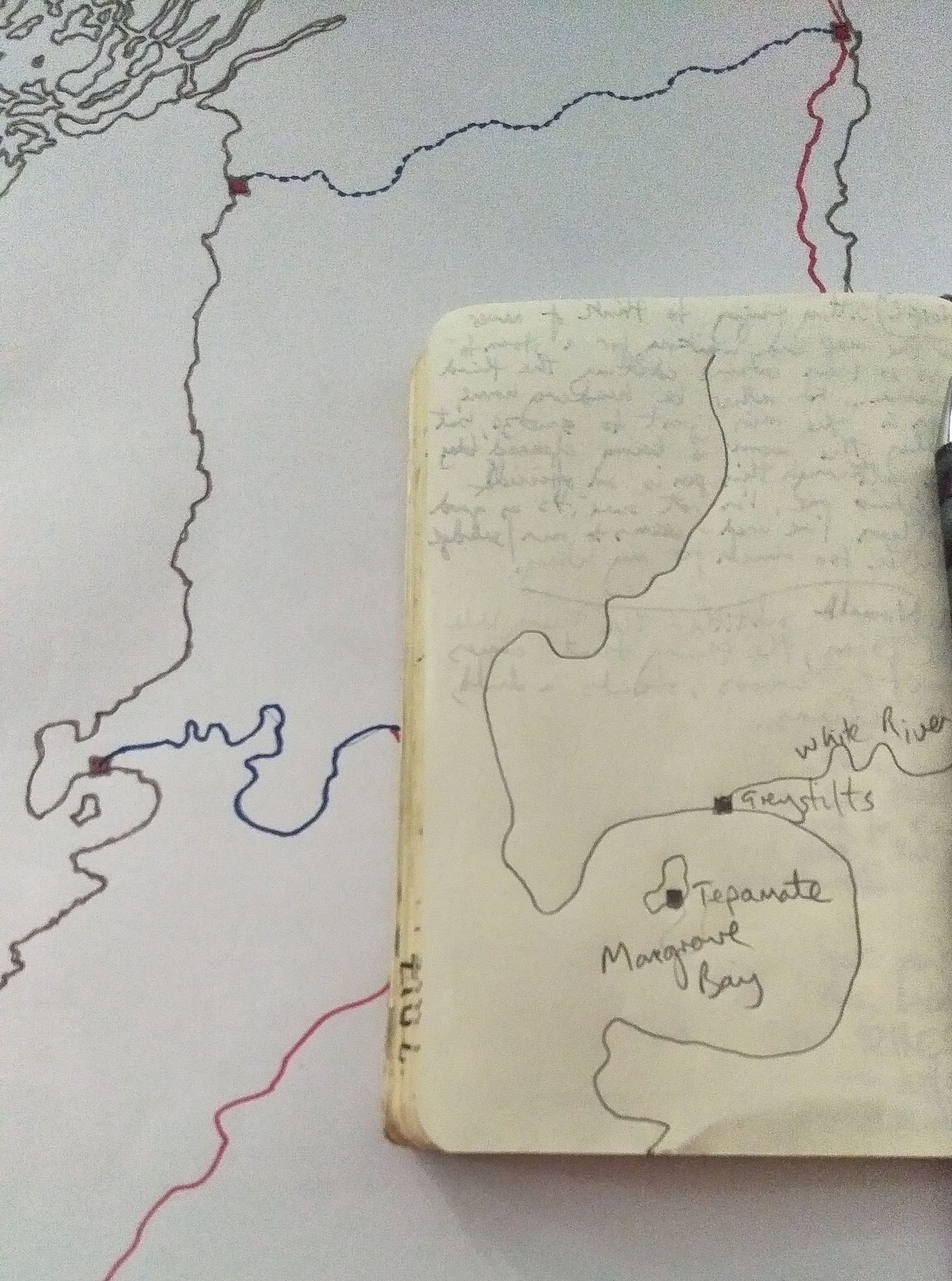

This notebook contains thoughts, musings, ideas, yes, but mostly it is for tracking day-to-day activities, as well as sketching maps and visual notes which are harder to translate digitally. I use a note-taking app — D-notes — on my phone and, of course, have several Scrivener projects backed up on my laptop, Onedrive, and Google Drive. Try as I might with pocket notebooks, it is just easier to record my fleeting thoughts on my phone and, I’d argue, that bit safer. The notes are themselves backed up on Google Drive.

One thing I would like to do, if I ever have time, is to transcribe all these notes on my phone by hand, perhaps into a dedicated Moleskine or similar and, conversely, take digital photos or scans of every page of every journal.

Last year, when we were in Europe but still paying rent on a place in Chiang Mai, we received the news that our house had been flooded. To cut a long story short, the landlady’s uncle had cut down a number of plants and trees outside the house, then left them in a big pile overnight, blocking the drain. The house lies at the bottom of a hill and, with that drain blocked, the water from a heavy rainy season storm had nowhere to go but inside. Although we were subletting the place, we did have things stored there, including, yes, you guessed it, some journals of mine.

I like beautifully crafted things that work, whether the Osmiroid italic fountain pen I received as a gift when I was seven years old and still use today, its nib perfectly worn to the slant of my hand, or another notebook gifted by Lydia, with a powerful, moving and wholly-applicable inscription. This particular notebook was used for Big Thoughts, as I recorded a difficult period in my life, using said fountain pen to do so, sometimes in black, sometimes blue, sometimes purple, noting down ideas and directions I wanted to follow, dissecting how to do this. It was, essentially, where I planned my route to leaving the UK on adventures.

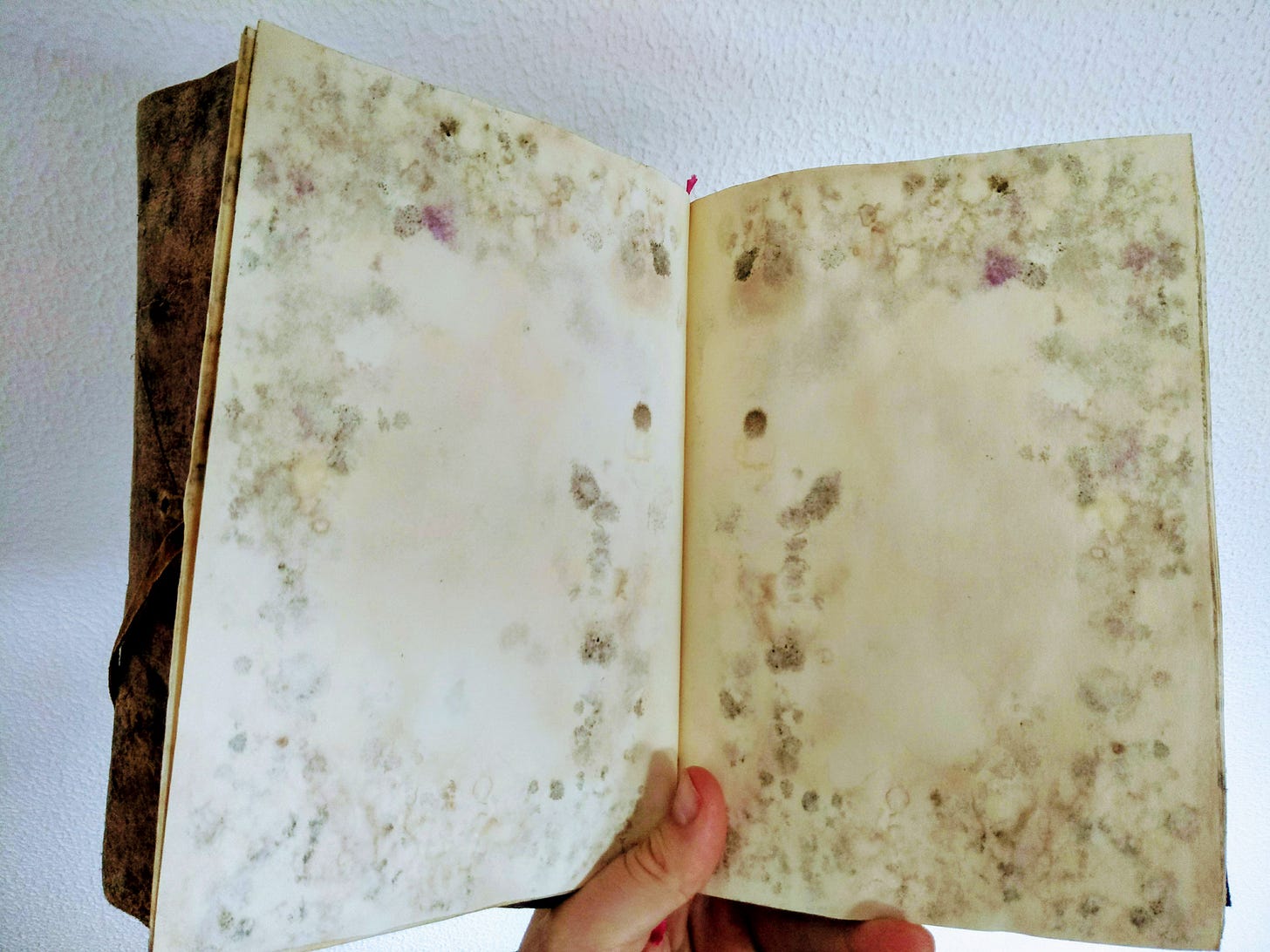

The notebook was soaked through, my words — and that inscription — disappeared into the jungle heat and humidity of the rainy season in northern Thailand.

I had sealed some pages, as I sometimes do, with masking tape — hiding things and thoughts that are best locked away. Not because they contain anything untoward or bad, exactly, but they represented a period of thought which was difficult and to be regularly reminded of that is not the best thing for my mind-state. I wonder whether these sealed thoughts survive or not, it is difficult to tell without opening the pages and, quite frankly, there is no need to do so, but holding the paper to the light suggests they may have done. Instead, I think I shall use these stained and warped pages for something else, a special project. But what, as yet, I am unsure.

I have cleaned the book as best I can, leaving it in the sun to kill any spores, but it is no longer the thing of beauty it once was. It has grown, it has gathered scars, aged and worn. It has become something new, something beautiful for different reasons. The pages still contain flowers I have pressed, now firmly melded to the paper, too fragile to remove. They are decorated with what at first I took to be mould, then realised was actually mostly ink, from where it took my words and pooled, forming new, unplanned patterns. These also have a strange beauty of their own.

Practically, the lesson I should have learnt here is to either always use waterproof ink or, at the very least, to photograph or scan my pages as I write them. There are other lessons too, lessons of understanding, loss and acceptance.

One of the worst things to happen to writer is to lose words. If you have read my piece on books, you will know that the works of Laurie Lee’s are important to me. When he was in Spain, filming with the BBC in 1969, his diaries covering the period 1935-1937 were stolen. The events of this time formed the memoir As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, published in 1969 — and the reason Lee was in Spain with the BBC. The final volume of his autobiographical trilogy, A Moment of War, was not published until 1991, and a major part of the reason behind this length of time was due to the loss of his diaries, and his desire to accurately portray and paint his involvement in Spain during the civil war. From when I first learn of the theft, when reading Valerie Grove’s biography; it was an idea which frightened me, something to whisper to the writer on the darkest of nights, or perhaps Halloween, “Your words will disappear, they shall vanish, be stolen from you”. A true horror story.

And then the horror happened. The loss was painful, of course it was, yet it was also less difficult than I had imagined it might be, and the pain was brief. Those words had served their purpose, the planning and ideas and directions I had set had been followed. I felt a curious sense of acceptance.

When we write, when we keep notes, perhaps we should accept we are not really ‘keeping’ anything. There are so many variables in life, so many chances for those words to vanish. We are merely caretakers, until time, or tide, sweeps all away. The key point, for me, is that it is important to build on the ideas and thoughts I record, to keep moving, to keep distilling and refining, a chemical process bubbling away in the head, the raw ingredients notes, imagination, lateral thinking, creativity and an acceptance that sometimes the experiment takes longer than planned. It is common for journalists to suggest writers seek immortality through their work and, I suspect, this is partially true, but story — true, deep story — has a habit of twisting away and becoming a thing of its own, it cannot be tamed or pinned to a page. Eventually, the words detach from the writer and go free, like Beowulf, or the Epic of Gilgamesh, author-less into the world and time. I actually like this idea. Story is more: it is a way for our species to connect the dots, to rationalise and theorise, and to be a part of something other, something vast.

I am still going to photograph every page of the cork journal, however.

Finally

There are sections of this newsletter missing, notes and drafts which remain just that — time may have stretched this year, but it seems that as the year sighs to a close, it is speeding up once more. I have more I want to say, more to share, but it will have to wait for now.

When you receive the next scheduled newsletter, I will be in France, assuming borders remain open, flights fly, trains roll and curfew and lockdown allow. Then there will be the issue of getting back here, to Portugal, even without the looming dread of a no-deal Brexit. Interesting times, indeed.

As I write this final paragraph, ‘our’ stork has returned to the nest nearby, displaying and clattering, defying the rain and sending a promise of spring to come. And spring will come.

Needless to say, the photographs accompanying this piece are of my journals, and mostly recycled from an earlier piece. Time presses on.