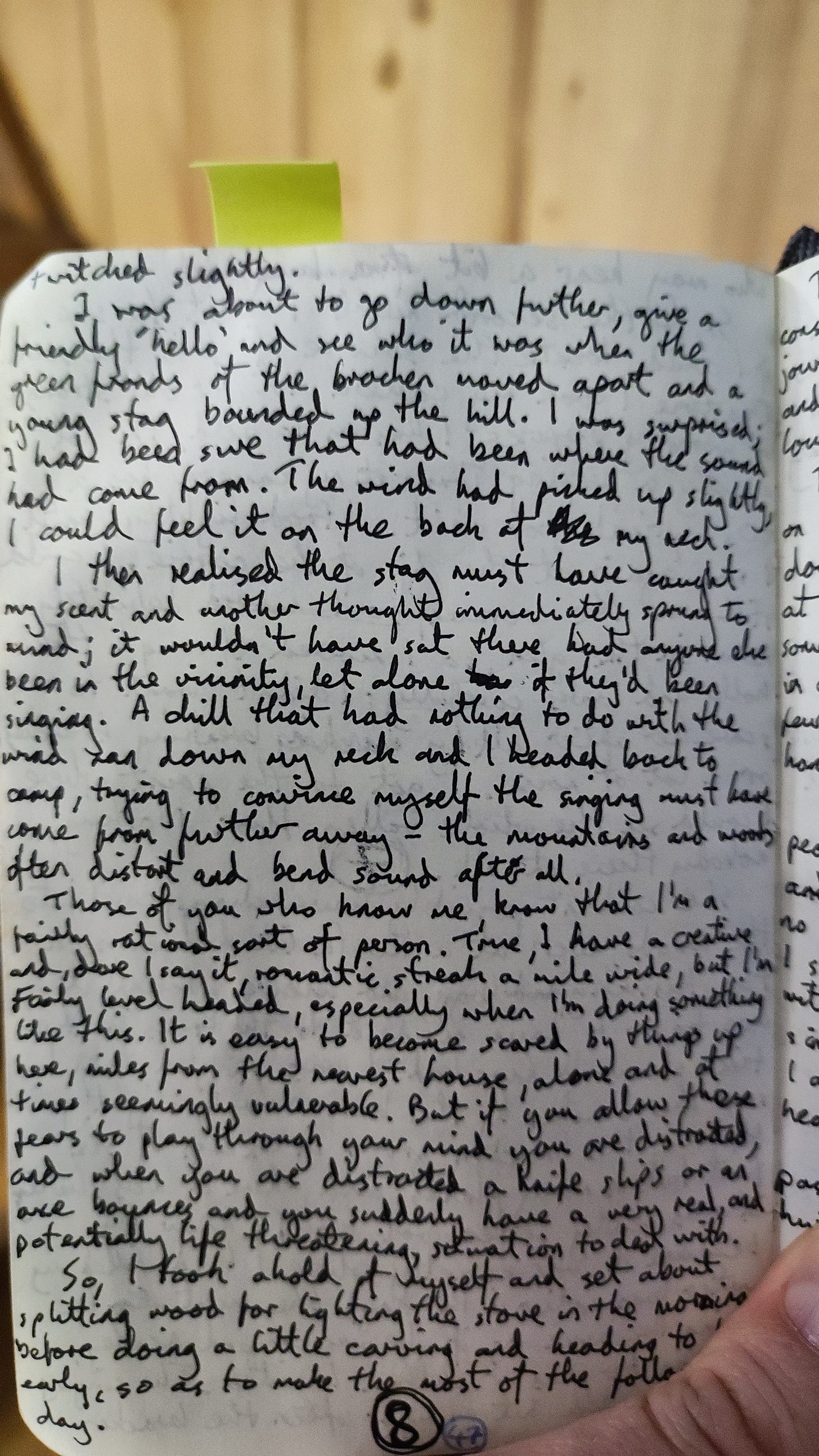

This is an edit and extensive rework of a post I shared on my sister’s website, back in late October, 2010. As I have mentioned in this ongoing series, I would handwrite each blog post, photograph it on my trusty pre-smartphone, and send it to her to then transcribe, edit and post.

For those of you who aren’t following my daily Notes from that time, in short, I left behind my life in the city, travelled north, and walked out into the woods. I would stay out there from late summer, through all of autumn, into winter, alone but for the wildlife, slowly becoming a part of a fascinating natural whole. That story is available at the A Fall in Time section of my Substack.

This piece was originally crafted in my second Moleskine notebook, the first thing I scribbled in those pages. I remember writing it during incessant rain, some point after sunset, the wind howling in the trees and whipping the oak branches above back and forth, tearing the occasional twig free, then a crash of a falling branch, all the while raindrops hissing in my fire and spitting, popping and tinkling when they fell on the hot billy can hanging above.

I was using my headtorch to light my writing way and, at one point, had to bat away a giant moth, who kept flying into my face, turning off the light briefly, then feeling considerable guilt when it decided to follow the light of the flames instead.

The next time a moth arrived, I left the light on, gently removing it when it tried to settle on my eyelid, more than once.

This tale—the one you are reading now—took place just after I had moved up to my third camp, but before I had moved into the natural shelter I was building; I was still sleeping in my hammock, below my tarp.

It was one of those beautiful late summer evenings that, at the point I turned the memory into words in my notebook, seemed very far away indeed.

The sun was low, and I was sitting in my hammock, writing in my journal, feeling content and satisfied with the world and my place within it. The previous night had been cold and had killed off most of the midges which had been plaguing me up to that point. The still air held a promise of another cold night, and I knew the season was changing again.

As I sat there, lazily swinging from side to side, scribbling away merrily, I heard something from the glen below me. I paused and cocked my head, listening carefully but, hearing no further sound, I resumed my writing.

There it was again.

I paused. It sounded for all the world like children playing. This was strange—I was a long way from any house, so assumed it was perhaps a family enjoying a late walk before the sun set. There would be about an hour and a half before it was too dark to safely walk through the glen.

To confirm my suspicion, I walked to the edge of the small natural bowl I was camped within, higher up on the eastern flank of the glen below, but could see no one. I waited, but there was no movement in the bracken, no flash of colour from the woodland beyond, nothing.

As I walked back to my camp, I rationalised that the family must have already entered the woodland opposite, following the deer trail rather than the coastal path, where I would have certainly seen them. The leaves at that point were much thicker, yet to fall, deadening sound and diverting noise.

I thought some more about it as the sun disappeared and the night fell. This was the obvious explanation—that or, perhaps, the sound had somehow travelled across the sea loch. This sometimes happens out on the west coast—sound can go a long way in certain atmospheric conditions but, when it does that, I usually heard more than a brief snippet or two. Perhaps there had been a light breeze for a moment, something which did not touch me directly, but carried the voices and laughter?

I spent the rest of the evening cocking my head and pausing to listen, to see if I heard anything more, but there was nothing.

The following morning also dawned beautiful and bright, promising a delicious, sunny day ahead. My water supplies were low and I had to fill my bottles and bags; it had not rained for some time, which meant the best option was to descend to the glen and the burn down there, the little stream which never dried up. It would be a good opportunity to test my tracking skills, try and locate where the children and, I assumed, their parents, had gone.

I am not a bad tracker, not seemingly magical, by any means—I am much better now than I was then—but I was confident I could track playing children. Humans leave obvious traces, nearly all the time—they rarely watch where they place their feet, and do not care what sign they leave behind, especially obvious in such soft ground.

I found nothing.

Not a print, not a scuffed area of moss, misplaced stone, or bent blade of grass. I moved further into the wood, eyes scanning constantly, hoping to find a thread to follow.

Then, I found a slight indentation in a patch of moss, and another a short distance away. It was about the right size for a small child and I scouted around and found yet another piece of the puzzle, and another.

I felt relieved that my tracking skills had not failed me, and I kept following the trail until I came to a patch of muddy ground, where water had seeped from the earth. There, as plain as in a nature guide, was a perfect set of badger prints.

I was pleased with myself—I continued, followed the badger and found where it had disappeared into a dark hole in a jumble of boulders. No children, but the thrill of following an animal was too great to let that worry me—now, I could return at dawn or dusk and sit quietly, observe the black and white striped head appearing from the sett, should I wish.

On my way back, and as I filled my water, I thought some more about the children. I must have been mistaken, the sound travelling from all the way across the loch, or perhaps bouncing around the coast somehow. I put it to the back of my mind, still excited about the badger.

That evening, I was again in my hammock, recording the events of the day, all those thoughts and feelings, continuing the long work which was unravelling the complicated skein of my years up to that point, teasing and retwisting and weaving tangled emotions into something stronger, more durable for the future.

I had made the most of the good weather and begun the construction of my natural shelter. The uprights were in position, postholes dug, and a sizeable pile of oak logs and poles gathered for forthcoming construction.

I paused in my writing, tilting my head once more, in the direction of the valley below.

There was a woman singing. A little strange—the sun would set within the hour and whoever it was would have to hurry back home, unless they were perhaps wild camping nearby in the glen, as I had done, before moving up the hill.

I listened a little longer, but could pick out no words. It wasn’t too surprising that someone would be singing—I did it myself, from time to time, in those first few weeks in the woods. After that, I would whisper song, but never raise my voice, as something within me rewilded, encouraged increasing silence.

For the second night in a row, I went to see if I could locate the source of the sound. This time, I took my camera, intending to use the zoom, as I had no binoculars with me. I could still hear the woman, definitely down in the glen, from somewhere near the burn I used to fill my water. As I got closer, I realised she was singing in a language I was unfamiliar with, but which tickled something at the back of my mind. I got to the edge and peaked out of my little woodland, down past the frost- and time-shattered crags and solid, dark holly trees below.

Nothing. Nobody there at all.

There was no way she could have disappeared into the woods, even at a run. And a run across that tussocky, boggy and uneven ground would have been foolish.

I was puzzled, but then I saw the tall bracken by the burn move a little. The air was still again, like the previous night, so I guessed she must be down there, perhaps also filling water bottles, or washing pans or clothes. The bracken, which I later used to help thatch my shelter, would often grow as high as two metres (six or seven feet), hiding all manner of things beneath and amongst its tick-laden fronds.

The singing did not start again but, for a few more heartbeats, the bracken continued to move sporadically. I wondered if I should say hello, but changed my mind, determining that perhaps whoever it was wanted the same solitude I myself had found. Instead, I began to turn back to my camp, so as to not intrude.

I noticed that the wind had picked up slightly, coming from behind me, blowing on the back of my neck and, a moment after I realised this, a young red deer stag leapt from the green bracken below, bounding across the glen and up the opposite slope, disappearing along the same deer trail I had walked earlier in the day, when I had discovered the path of the badger.

The stag must have caught my scent when the wind picked up and decided not to bed down there for the night, not with humans nearby. A chill which had nothing to do with the wind ran down my spine—it would certainly not have stayed there if another human had been nearby, singing.

I walked back to camp a little faster than I had descended, despite the steep gradient. As I did, I tried to convince myself that it was simply another case of sound travelling in a strange manner. I certainly harbour a strong creative and, dare I say it, romantic streak, but on the whole I approach life based on a relatively firm, science-based, grounding.

I’m level-headed, especially when out in nature—it can be all too easy to trick your own mind into worry, which becomes fear, which morphs into terror. If you allow this, then you become distracted and, when distractions occur, you either run back to civilisation or have an accident; you burn yourself, a knife slips, an axe bounces and, suddenly, an irrational thought turns into a very real and potentially life-threatening situation to deal with.

I took a firm hold of myself and set about splitting wood for lighting my stove in the morning, followed by a little carving, then headed to bed early, exhausted by the day and readying myself for another physical shelter-building session the next.

The following sunset arrived and I had consigned the events of the previous evening to my journal, spending the day working on the shelter frame and rather pleased with the results. This physicality had left me tired, again, but also rather delighted; I would have a cosy home to face the colder nights, if only I put in a bit more work. I was busy making a blackberry and raisin steamed pudding when I heard it.

Men’s laughter. Loud and sharp, once more from the same area, below. There was a voice, talking loudly but, again, not in a language I could decipher, followed by more laughter.

The hair on the back of my neck stood on end. I didn’t want to go look because, deep down, I knew I wouldn’t see anyone if I did. By staying in my camp, concentrating on making my dinner, I could almost convince myself it had been hikers, sharing a joke.

I calmed my racing heart, took a few deep breaths and simply got on with the task at hand. There was nothing else I could do, after all.

After that point, I heard several more voices on the wind. I heard people talking when it was calm and still, I heard laughter and, on one other occasion, children playing, just below my camp. It reached a point where it no longer frightened me quite so much, I passed through and beyond a period of worry. And it is important to note that this was not a fear of ghosts, but a worry that my mind was playing tricks with my senses, the isolation getting to me in a strange fashion. A bird calling could be a woman singing? A deer barking a man laughing? Perhaps I was simply hearing what my subconscious wanted me to hear?

Or, perhaps, it was something else? Maybe an echo of a past no longer distant? Memory and emotion deeply embedded in place, out of time perhaps, but finding a receptive audience nevertheless.

Whatever it was, I knew it could not hurt me. I have always felt safer from other humans whilst out in the woods and hills than in a city, after all, and the dead do not seem to wish me harm, why would they?

Many weeks after that point, not too long before I left the woods, I was down in the glen, combing the beach after a storm. I went in a slightly different direction to normal, skirting a bog on the opposite side to that I had previously taken when it suddenly dawned on me that I was walking across the remnants of a patch of run rig: the ancient crop growing system of Scottish agriculture. This is distinctive, with ridges and furrows, and I counted at least eleven such bumps. It was not large, but it would have been enough to sustain a few families. And there, in the corner of the field, nestled beneath crags that, had I climbed directly up and over, I would have arrived at my own shelter, lay the tell-tale bumps of a one-roomed, traditional Highland dwelling, probably a blackhouse (although I know there is debate about this term, and when it first came into existence. This particular ruin was certainly a couple of hundred of years old, at the most modern, likely much older than that).

After this, as the bracken died off and the grass and other plants withered for winter, I found several other places in the woods which showed signs of ancient habitation, whether other buildings, more rig and furrow, or even the remains of what might well have been the original Road to the Isles1, long before the coming of Telford and his engineers to the area, and likely the same to have been followed by Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart—or Bonnie Prince Charlie—himself. (He first arrived on the Scottish mainland not too far from where I was, leaving after the defeat at Culloden from the same area. The famous Treasure of Loch Arkaig also arrived not too far away, before all that gold was lost to history.)

Once, before the clearances and subsequent, continued decades of emigration, this part of Scotland was certainly full of laughter, that of men working on the land or preparing their small boats for the fishing, of women singing whilst gathering clean water or waulking the cloth, and of their children playing.2

Perhaps there is a rationalisation, or perhaps the space I had decided to live in for a time was welcoming me, gifting me aural flashes of now long-dead, previous inhabitants? To this day, I do not know the answer. I do know that the land can carry stories, nestled within the rocks and the peat, washed by the ocean and drenched by rain, but stories which persist, nevertheless.

It was only months later whilst researching another story—after I was back in a bed, beneath a slate-clad roof, in a house designed by Thomas Telford himself—that I realised that the language I had heard was undoubtedly Gaelic.

If you want to see more from this waulking song video, the original 15 minute 1941 film can be found here. If you do follow that link, ensure you also read the notes below it, which are fascinating. You can also see examples of the traditional blackhouse I mention. And that map at the beginning of the film? There’s no Orkney, no Shetland—bear in mind, this was released as the very real threat of invasion was at its highest, and both Shetland and, especially, Orkney, were high value, strategic military targets.)

And, if you would like to read a further seasonal and spooky tale from me, a similarly-true one from when I lived in Orkney, follow this link. It sometimes still sends a shiver down my spine even now, when I think about it.

Finally

As ever, I am immensely grateful for you reading this. If you do feel my work has value to you and you can afford to, there are several ways you can support this publication.

I am so thankful for everyone who clicks that little heart, restacks, or shares my work elsewhere—as someone who struggles with self-publicity and marketing, each of these shares means a lot to me. You don’t have to part with money to support this letter.

If, however, you can afford to, then a paid subscription is a super way to help. I currently have a staggering-to-me 1743 subscribers to The Crow’s Nest, of whom 15 are paying readers. Needless to say, this falls a long way short of the conversion rate deemed a successful letter, but it still makes me very happy that there are those who choose to support my work in this manner. Thank you.

If you do not want to subscribe but still want to support me with money, then I can also accept one-off payments at my KoFi account, here:

Finally, another way to support me is just to say hello, or leave a comment. Although it can take me some time to respond, I do try and reply to each and every comment I receive, and I am incredibly thankful that there are so many of you who do take the time out of your own busy days to write something in response. That is a beautiful thing indeed.

The weekly round-up—now up to week seven—of A Fall In Time will be going out as usual on Saturday morning, half-past-seven French time.

Many, many thanks for reading,

Alex

None of the sites I found are recorded in CANMORE, the Scottish archaeological catalogue; some things just disappear back into the woods, hiding for decades, then centuries or millennia, before being stumbled upon (or deliberately searched for) once again. One day, I have a vague temptation to return and properly record some of those I found or, at the very least, add those sites to the catalogue, complete with the photographs I took at the time. (Growing up in Orkney, I know of similar unrecorded sites. Some of which are probably a lot, lot older than those I found in those woods. Similarly here, in this corner of France—there is just so much archaeology and, once you know what you are looking for, it is impossible to unsee it everywhere you go. Our species has long altered our world, leaving clues and messages, if we but look.)

To give a flavour of what life would have been like in those now roofless shells which were once homes, here’s a snippet from Alexander Carmichael, whose (at times controversial) Carmina Gadelica is a treasure trove of folklore and lifelong observation:

“The house is roomy and clean, if homely, with its bright peat fire in the middle of the floor. There are many present—men and women, boys and girls. All the women are seated, and most of the men. Girls are crouched between the knees of fathers or brothers or friends, while boys are perched wherever—boy-like—they can climb. The house-man is twisting twigs of heather into ropes to hold down thatch, a neighbour crofter is twining quicken root into cords to tie cows, while another is plaiting bent grass into baskets to hold meal. The housewife is spinning, a daughter is carding, another daughter is teazing, while a third daughter, supposed to be working, is away in the background conversing in low whispers with the son of a neighbouring crofter. Neighbour wives and neighbour daughters are knitting, sewing, or embroidering.” (Carmichael, 1899, p. xix)

Carmichael, A. (1899). Carmina Gadelica (1st ed., Vol. 1).

Hauntingly beautiful. I have no doubt the Gaelic voices you've heard on the wind were flashes from times that are, from our perspective, long gone. We nowadays may rationalise it in one way or another, it doesn't really matter, because the Land remembers.

Really evocative -- thank you